Have you ever suddenly noticed an area which you walk past every day – really seeing it for all its nooks and crannies, colors and shadows? Or gone to a place for the first time and felt its power? Has this inspired you creatively – to dance and choreograph, to improvise and collaborate? You’ve tapped into the unique magic of site work. Yet the challenges that can evolve on the way to getting there – weather-related, legal, technical and more – can certainly be less magical.

To get a better idea of what these processes can be like, as well as how to ensure that they run as smoothly as possible (as much as we artists can control that), Dance Informa talked with three choreographers experienced with site-specific work: Heather Bryce (Bryce Dance Company, NYC), Margi Cole (The Dance COLEctive, Chicago, IL), and Callie Chapman (Zoe Dance, Boston, MA). They also all shared something about how and why site work can be so very well worth the hassles of handling these challenges. Let’s jump in!

Heather Bryce

Heather Bryce’s ‘Lonesome Bend’. Photo by Britten Leigh Photography.

“The largest site work piece I’ve done was called Lonesome Bend, named for the former hamlet (small cluster of homes) that was flooded to create a holding basin to protect the larger towns in the area from flooding. The site is now used as a recreation area called Wrightsville Reservoir.

We collaborated with the local community in order to build the piece and invited them in to the performance as participants. We also collaborated with a visual artist and four musicians. The creation of the piece involved research on the history of the site and gathering any artifacts that might be useful, including photos from the local historical society.

Even with a rain date, we had an additional plan B, such as a tent for the videographer and musicians. It actually did rain on the performance date, and we decided to hold the performance anyway, in part because it would have been challenging to inform our potential audience members of the change (without Facebook events and alerts as much as a built system as they are now).

Heather Bryce’s ‘Lonesome Bend’. Photo by Britten Leigh Photography.

Working outdoors adds to Murphy’s Law. When I got to this site, for example, I knew things would change each time we were there. Another thing to consider: ask every little step of the way, do I need a permit? It’s also important to make sure the site staff and administration supports your ideas and process.

One of the amazing things about site work is that it makes the audience see the site in a new way. Site work can also be more accessible to a broad range of audiences – people experience the rehearsal process and product. In the site work we have created, we have chosen to hold the performance free of charge; this is where grants and crowdfunding can be helpful to fund these projects.

I’ll be continuing to create site work, with plans for a few new works. One is a site mobile piece in continuation of the Lonesome Bend series – related to displacement and loss from flooding caused by natural disasters in a variety of communities (specifically focusing on the present need in Puerto Rico). I’d like to spur discussion, involve affected communities in the work, and help support communities in need – with, even now, people are standing in line for supplies in order to meet their basic needs.”

Margi Cole

“There are two main ways, that I’m aware of, to make site work – to adapt a pre-existing piece to fit a space, or to make a work around a space. I tend to make a work around a space; I’ve found that it comes together better and honors the space. I think of the space as a container for the work, as well as often an inspiration for it.

I love how site work allows audience members to leave when they want, engage with it how they want. It allows them to have ownership over the work, and to see things through a different lens. It can be in a space where only five people can experience the work, or where hundreds can, such as a state fair. It opens up more possibilities.

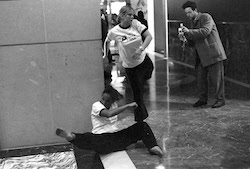

The Dance COLEctive. Photo by Jason Salerno.

In one site work, Gorham’s Bluff, we performed on southern porches. They’re important in the south, a social location. This social custom was the catalyst for the work; we wanted to highlight more than just the physical space but also what happens there. We went porch to porch, dancing and incorporating community members.

In Plain Site was another site work at the Illinois State Fair. We purposefully performed everywhere that was not a stage, to bring attention to spaces not otherwise seen. We danced for three days on the fairgrounds, six to eight performances each day, with eight dancers.

Half of the performances were publicized, and half were not. When audiences didn’t know it would happen, they would break the fourth wall. This built a more mutual feeling between audience and performer. It brought into question social airs, how we interact with one another.”

Callie Chapman

“As I’ve developed as an artist, I’ve grown into making work around the space more often. Working outside of a proscenium stage context, actually choosing the space in which you present a performance, you are sometimes entering into a non-controlled environment (and that’s the beauty of it).

An experiment that I started in summer of 2014, entitled Dancing in Favorite Spaces, took place every Friday in a different public space. One chosen space was where there are rows and rows of benches facing each other. There was no music or other audio, so some passersby weren’t sure if it was a performance.

Yet there was one runner who stuck around for the hour of the piece (pretending he was stretching). Without music or a sound ‘score’ to accompany movement, there is ambivalence as to whether or not people are invited to watch or participate. In my experience, only the boldest address their own presence in watching or taking it in.

Callie Chapman’s ‘Soaked’. Photo by Yayue Ding.

With Soaked, the dancers were in a swimming pool at a Boston Sports Clubs location as part of the inaugural Illuminus Festival. They had to work with water along with the dance, such as with breathing and adjusting to the cold, which we had rehearsal time every week to do. The dancers did well because they had that time to learn how to adapt to working in water.

And during the performance, as some technical aspects broke down, they improvised beautifully, and audiences gave very positive feedback nonetheless. There are so many facets like these to site work, and often [as a choreographer], you have to do it on your own.

My advice to aspiring artists who would want to work within a non-traditional environment that possibly hasn’t been used as a venue before: know when to ask questions. Assumptions cannot be made, since you are possibly doing something no one has done before.

Leave a lot of time to try working out what you need, and how many variables you can handle as part of your work. City entities can be slow, if you need permits, and you don’t want to be in the middle of a performance and there’s something that wasn’t taken care of and now they’re shutting your performance down.

Also, with smaller grants, try asking for just one aspect of a work, such as to hire a videographer. Think simpler. Do what is manageable for you and your team. Sometimes what you’re attempting might be too much too fast. Or maybe that’s part of the thrill?”

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.