By Rain Francis.

Rudolf Nureyev was one of the single most influential people in the history of dance. This year marks 20 years since his untimely death, but also 75 years since his birth. In celebration of this great man, many special events, gala performances and tributes are taking place worldwide in 2013. There has been so much written about him, and he has become something of an enigma. But what was he really like? We ask two professional dancers who knew him personally, Frederic Jahn and Patricia Ruanne.

Jahn and Ruanne are both involved with The Nureyev Foundation, and worked with Nureyev for many decades during their illustrious careers. In Patricia’s case, this relationship began in 1964, when Raymonda was presented at the Spoleto Festival in Italy, during the epoch when Margot Fonteyn’s husband was shot. For Frederic, it began in 1969, when Rudolf staged Don Quixote for The Australian Ballet.

How well did you know Rudolf Nureyev?

Frederic Jahn

I began to know Rudi better when we were working on Romeo and Juliet. I had worked with him before, as a very young corps de ballet member of The Australian Ballet. I was cast as the Old Don in Don Quixote, as Helpmann’s second cast, so I was privy to a lot of personal information, which was a tremendous learning curve in stagecraft.

Rudolf advised me to go to Europe, indicating that I should benefit from a wider professional platform than could be found in Australasia. This interest in a young dancer’s future was typical of the generosity he showed to fellow artistes. In my mind, I didn’t understand why he should single me out, but he clearly recognised some potential in me that I didn’t know I had. These ‘good old days’ were the platform of our relationship.

We discovered that most of the time he was by himself in London when he was choreographing Romeo and Juliet. Everybody thought that being a celebrity, he was wined and dined every night, when in fact he was just in his flat by himself. We would drop by and go to lunch or dinner. We established a close relationship, but I don’t know if we could say we were real friends. I felt he had trouble trusting people, and rightly so, as many used him for their own political ambitions, and still continue to do so.

I once dressed him in Italy; the dressers were scared of him so the management asked me if I would do it. I was the interim Ballet Master in Naples for the time Nureyev was there. I felt I was a friend, and it felt just as if you were helping a chum next to you do up his costume. The performance was already 20 minutes late, and a public of 3000 excited Italians were all clapping in unison to get the open-air show going. Italians can be very rowdy. He wasn’t going to be rushed, and the more noise they made, the gigglier he became. The management was knocking at the door, and I had to keep telling them he needed a few minutes more, at which point he said, “Ricky, have you heard the story about Bear and Rabbit sitting on edge of the wood?” I said I hadn’t, and he proceeded to tell me this scatological tale. We both left the dressing room giggling like schoolgirls, passing the fuming theatre management. Needless to say, when he came on stage, the audience was in a frenzy. He had in fact calculated that being late would drive the audience to this point, and he would give a performance that would be, for many people, a life-long memorable event. I felt that incident bonded us, and became the origin for many dinnertime anecdotes.

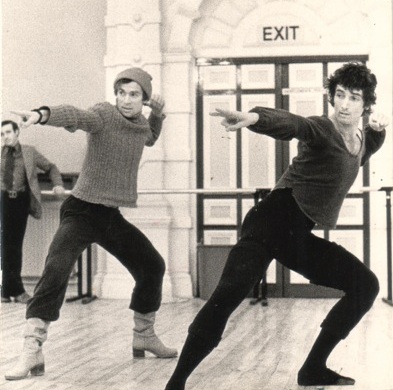

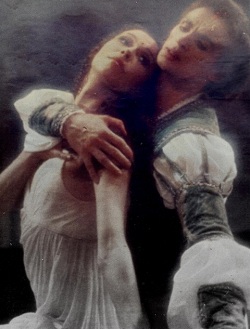

Rudolf Nureyev and Patricia Ruanne

Patricia Ruanne

I came to know him as well as he would allow. We had a good working relationship as dancers, and certainly he never gave me personally any ‘grief’ as a partner, which was not always the case with other dancers!

This agreeable understanding intensified once I went to join him in Paris. There was much discussion about the development of his dancers and I began to learn things on an entirely different level. Equally, he was always generous enough to listen to my thoughts on a subject, acknowledging that being on pointe was one asset he had never mastered. His demonstration of professional respect and affection to both myself and also to Frederic when he was there was naturally very helpful towards the Paris Opera dancers’ perception of us.

He frequently asked me to be hostess to his host at his home in Paris, so I met some fascinating people and we had a lot of fun. He couldn’t bear pretentious posturing; some folk were never invited back, or we would retire to the kitchen on the pretext of checking whether his cook was drunk yet, and try to dream up some plausible excuse for getting rid of someone who was boring him to tears. His proposals were generally along the lines of something dreamed up by Sweeney Todd; rather gory, but very funny. Lord knows what his guests made of the shrieks of laughter echoing from the back pantry!

He trusted me quite early on with the knowledge of his illness, and I spent every Sunday with him once he was obliged to be hospitalised towards the end of his life – something I remain glad to have been able to do.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about him?

Frederic Jahn

That he was bad tempered and rude and had no respect for others. He was not. It takes two to tango. Rudolf reacted to how people reacted to him, full stop.

Patricia Ruanne

I agree. I have seen him explode, but it was never without just cause. He had no time for laziness, indifference or lack of commitment to our profession. ‘Wasting time’ appalled him, given the brevity of a dancer’s performing life and he was incapable of understanding a lack of enthusiasm for anything related to the stage.

What was his greatest legacy?

Patricia Ruanne

This is an almost impossible question to answer. For my generation – and those who were able to see him perform at his best – there will forever remain the image of just how much can be accomplished by sheer hard work, dedication and never falling into the trap of believing your own publicity.

Personally, I think the strongest link to future generations will be the fact that he was also a great teacher, and instilled this care for others into so many younger dancers, some of whom are now directing companies. Watching them coach dancers in roles they once performed themselves, one can see the influence of Nureyev quite clearly.

He once said to me, when I was struggling with an exceptionally difficult company who appeared incapable of coping with his challenging choreography, “Are they doing the best they can? If so, and even if it’s not the standard you would like to see, you have to love and respect them for giving all that they are capable of.” I think that says a lot about the kind of man he was, and I try to apply this great advice always.

What can students today learn from him?

Patricia Ruanne

Don’t waste time – there’ll never be enough of it. Never give up on yourself. Always work to the best of your ability, but don’t let yourself sink into a depression when in a bad patch. Just keep at it – it will come back if you don’t frustrate yourself mentally. Keep your sense of humour and care about yourself.

Rudolf did not have a perfect physique and had to overcome many technical problems. Nonetheless, he had the most sensational career. It’s a perfect example of belief in self, dedication and determination.

For more information about Rudolf Nureyev and the list of tribute events taking place this year, visit www.nureyev.org.

Photos courtesy of Frederic Jahn and Patricia Ruanne. Top photo: Rudolf Nureyev and Frederic Jahn in rehearsal.