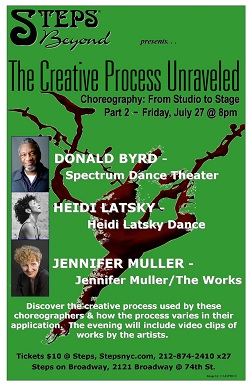

Steps Beyond: The Creative Process Unraveled with Donald Byrd, Heidi Latsky, and Jennifer Muller

By Leigh Schanfein.

Steps Beyond regularly holds a lecture series in which distinguished artists discuss their work, influences, process, history, and everything in between in the hope that dance professionals and aspiring artists take this information in to enhance their own work and find inspiration. The series, which takes place at Steps on Broadway in New York City, provides the opportunity for connections within the ever broadening sphere of the dance community.

I attended Step’s most recent Artists Talk entitled “Choreography From Studio to Stage” where three very successful artistic directors were invited to discuss their work with an engaged audience. Jennifer Muller is artistic director of Jennifer Muller/ The Works, which she founded in 1974; Heidi Latsky is artistic director of Heidy Latsky Dance, which she founded in 2001; and Donald Byrd is artistic director of Spectrum Dance Theater. The talk attracted an audience of dancers, former dancers, teachers, choreographers, festival directors, and aspirants to all of the above.

What I heard was fascinating and could have gone for twice as long if we’d had the time. I couldn’t recommend more highly that if you have the opportunity to attend a lecture or discussion that you definitely take advantage of it and garner the valuable information that the people who have created the world of dance as we know it today are ready to give to those who ask.

What I heard was fascinating and could have gone for twice as long if we’d had the time. I couldn’t recommend more highly that if you have the opportunity to attend a lecture or discussion that you definitely take advantage of it and garner the valuable information that the people who have created the world of dance as we know it today are ready to give to those who ask.

Here is just a taste of what the talented choreographers presented and discussed:

Jennifer Muller gave us insight into the development of her work Bench, which was a commission inspired by the film An Inconvenient Truth. For this work, as with any work, she began with a concept, a “pin prick”, from which to develop, because without it she finds the process too vague. Muller comes from a background of movement with reason that requires a deliberate process that might even take on a narrative arc.

For Bench, Muller considered how we interact with our environment and what influence we hold over it. She used video as well as an actual bench on stage, neither of which as an acute focus but either of which can take on multiple roles and which remain central to the relationships that play out on stage amongst the dancers. Her video was a meticulously constructed orchestration of images to depict themes relevant to each sub-portion of the piece, projected as a strip rather than a full backdrop to aid its serving as an element rather than the focus. Video doesn’t have to be its own thing; it can be there to create an environment.

Muller emphasized that she always tries to find a new vocabulary or structure unique to every piece she does. This might come about because of certain rules she decides to enforce for herself regarding how she will approach the piece, what she will allow herself to do, and sometimes it is her self-imposed choreographic restrictions that can make the process very difficult. For example, she decided that for Bench, the dancers would stay on stage the entire time, and for a 33 minutes piece this was quite a challenge.

Mulller is often criticized for having multiple things going on simultaneously that pull the viewer’s attention in two or three directions at once, but this is something she does deliberately, practicing how she can create a double focus effectively. In fact, thinking about and re-thinking about the choreographic structure is something she does a lot; she re-choreographed one section of Bench five times and completely changed the music four times! Muller loves collaborations with composers and designers and fully understands the impact her artistic partners can have on the final work.

Heidy Latsky discussed and introduced us to her continually evolving work Gimp, or as she calls it, The Gimp Project. It began in 2006, took three years to make, and after six years it was re-done with new choreography, staging, and lighting. The work is born out of the commission of an amputee artist who wanted to use choreography in her artwork.

Latsky had never worked with disabled non-dancers and dancers before and this was a starkly different experience for her. She would start with one idea and have to completely change it because she realized that she couldn’t go about things the way she usually did, which was to work from her own body and create from what she felt. She had to take the work out of her body, “I didn’t want them to do what I could do”, she explained. Latsky had to find out what they could do well, be it intricate upper body articulations, fluid movement across the floor, or falling.

The artist who first came to Latsky normally wore prosthetics, and had started with them in the rehearsal process, but found that she was using them for safety, and that she had to at some point discard them to reveal a beauty in her movement that was real, fierce, and vulnerable.

Latsky had difficulty reconciling her wish to make a sociopolitical piece and her desire to keep it about and within the art. For the dancers, more so than for herself, the piece had very strong political statements, and it was important for the dancers that this not be diminished.

This piece has been performed and developed over many years, and was even performed just this July at Lincoln Center in New York City. It has had many casts, which is startling considering how specific the movement must be to each performer. Each dancer has different abilities.

Donald Byrd brought us one of his renditions of the classic ballet Petroushka. He has already created the Harlem Nutcracker and his own versions of several romantic ballets.

Byrd started out with a post-punk/grunge version of Petroushka that took place in a club, with a mosh pit. He came away from his own work disappointed; he was disillusioned with the proscenium stage and how it gave the viewer a false power of perspective. He decided some time later to return to the ballet, turn it into immersive theater, and develop it into a real fair for a “carnie” Petroushka. Was it a tale of tragically misplaced love, or was it simply sad and pathetic? For this version he had the audience move through an actual small fair and several rooms in a fun house, including a room where the dancers appeared via surveillance cameras looking in on characters in their rooms. The arrangement was extremely voyeuristic.

Byrd finds that he is now more into stage directing his already-choreographed works, trying to find the best way to tell his story. The movement is the text of the story and Byrd is trying to clarify what the author states, to elucidate his meaning. He will leave it to other companies to stage his works as they were originally done!

These three unique artists continue to push the envelope and foster the evolution of their work and our art form. It was a pleasure to hear about their choreographic process, concepts and challenges.

Photo: Heidy Latsky Dance, The Gimp Project. Source www.thegimpproject.com/gimp/gallery