City Center, New York City

October 6 2012

By Tara Sheena.

Fall for Dance descends annually in the wake of the cold air’s return to New York City to present dance spectators old and young with a smorgasbord of satiating performances. One rule: come hungry. Taking place at City Center since its inception in 2004, this year’s festival included 12 evenings of dance and 20 companies spanning over 10 countries with 5 uniquely matched programs. I had the privilege of attending Program 4 on October 6, 2012 featuring Bharat Natyam performer Shantala Shivalingappa, a pas de deux from Pacific Northwest Ballet, a quartet from postmodern choreographer Jodi Melnick, and the Hawaiian dance ensemble Ka Leo O Laka I Ka Hikina O Ka La.

The renowned Bharat Natyam performer Shantala Shivalingappa opened the evening’s performance with incredible grace and fluidity that was truly mesmerizing. Shivalingappa was the sole performer of this classic Indian dance form, but was accompanied on stage by three musicians and a vocalist. This contained world enacted rumination on Shiva, the Lord of Dance, and Ganga, the Goddess of the sacred river Ganges. Shivalingappa began her solo with a traditional offering that begins most Bharat Natyam performances. This gestural acquaintance is highly meditative and is directed at both her accompanying musicians and the audience, gently ushering us into her magical world. The highly articulate hands that welcome us into these conceptual etudes on Shiva and Ganga constantly whirled and twisted over highly percussive, grounded legs. In this traditional Indian dance form, the music and movement mimic each other in a completely engaging manner; stomping of the feet and twists of the head and torso power the musical elements to follow suit, and vice versa. It was never completely apparent who was leading who, but the result managed to avoid an all-too-literal interpretation of music and movement. By the end, boundless knee spins led Shivalingappa around the stage and the audience roared in applause—enamored by her disciplined movement but, more so, by the sacred experience she provided.

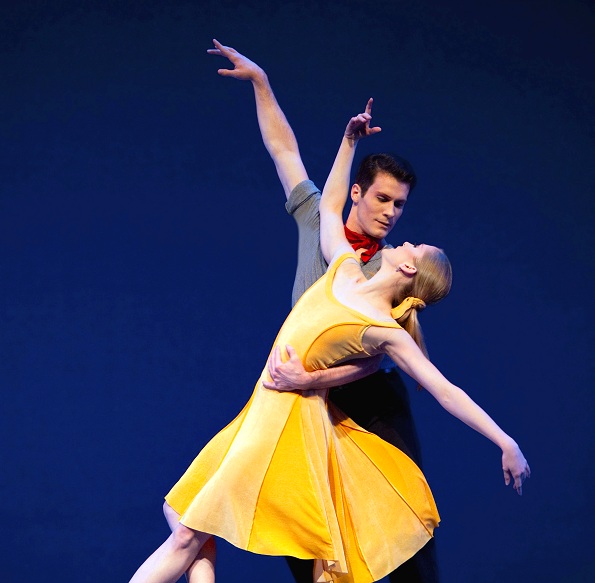

One classical form was followed by another in a pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s Carousel (A Dance) by Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Carla Körbes and Seth Orza. Körbes depicted a hesitant, submissive female figure to Orza’s urging comfort, alluding to the “poignant, doomed nature of the couple’s relationship”, as explained in the program notes. Set to the familiar, show-tuney music of Richard Rodgers, Orza seems to cushion Körbes’ constant falling at every chance. Both a literal movement and figurative statement, Körbes slid across the floor en pointe and before it looked like she could hit the deck, Orza was there to prop her back onto her legs to keep going. These moments were exciting. They happened with precision and abandon, but grew old fast when the promenades and overhead lifts started to become overwrought. Wheeldon seemed to exercise these fall-and-catch mechanisms too much, so they lost their initial excitement by the end of the piece. In fact, so did this fictional relationship. The game of cat and mouse that Orza and Körbes engaged in became more of an overly dependent farce; Körbes’ submission was lost to Orza’s ambivalence and the performance did not leave me wanting more.

I have wanted to see the work of Jodi Melnick for a long time. As a descendant of powerful postmodernists Trisha Brown and Twyla Tharp (among others) and a recent recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, I have wondered what kind of work she would produce under this myriad of influences. Melnick along with performers Jon Kinzel, Hrisotula Harakas, and Kayvon Pourazar, as well as acoustic-electronic music group People Get Ready made up Solo, (Re)Deluxe Version. The top of the work found Melnick onstage alone, red hair slightly disheveled, in a metallic silver jumpsuit. Was this the postmodern dancer of the future? Maybe not, but at least an imagined version of such. Not surprisingly, Melnick’s movement was at its most clear and engaging when she performed it—she has an unblemished sense of articulation that is never forced. This relaxed motion makes it as if water is running through her bones, unobstructed, in a gentle, steady stream. Joined by Harakas and the pumped up musical styling of People Get Ready, the movement was amplified in this beautifully oxymoronic meeting of post-rock and postmodern dance. The movement’s stripped down, casual quality was further supported by the removal of the upstage scrim, completely gutting the usual masking of the large City Center stage. Even on this massive scale, Melnick found a way to keep her detailed work intimate and personal.

As someone who was not familiar with traditional Hawaiian dance forms before this night, I can now say that I am definitely a fan. The ensemble of dancing men and female musicians that make up Ka Leo O Laka I Ka Hikina O Ka La, led by Artistic Director Kumu Hula Kaleo Trinidad, ushered me into this energetic world. Wearing nothing more than green loin cloths and flowered headpieces, this eleven-man army moved with the groundedness that resembled many African dance forms, while maintaining the precision and physicality of trained Olympic athletes. Even the female musicians were perfectly choreographed in their synchronization of the traditional ipu, a pear-shaped instrument made from gourds that provides a clear beat to most Hawaiian dance forms. Repeated squats, deep lunges, and wide stomping found vibrant, rhythmic patterns against the ipu’s percussive accompaniment. The movement and music seemed like a ritual performance that was uprooted from its traditional setting for the proscenium stage. This high-energy performance was quite the crowd pleaser and a perfect conclusion to the night. We feasted on dance and were all full. ‘Til next year.

Photo: Pacific Northwest Ballet, Wheeldon. Photo ©Angela Sterling