By Stephanie Wolf.

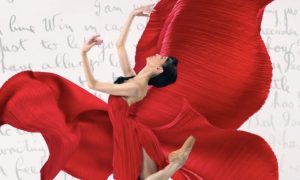

“Emphatic, full-bodied, theatrically dynamic, virtuosic,” these are just a few of the words used by Artistic Director, Donald Byrd, to define the style of dance currently offered by Seattle’s Spectrum Dance Theater. As a burgeoning venue for contemporary dance in America, Spectrum is making literal and figurative leaps and bounds. The organization, despite an unfavorable economy for the arts, is expanding its audience reach, providing a stable working environment for its dancers, and of course, finding means for artistic exploration.

Byrd began his formal training in Boston at the Cambridge School of Ballet. He furthered his studies overseas at the London School of Contemporary Dance. While there, Byrd realized he wanted to pursue the art form professionally. From London, Byrd traveled back to New York City to begin what would become an illustrious dance career, performing with the likes of Kathryn Posin, Gus Solomons, Jr., and Twyla Tharp, among others.

Byrd began his formal training in Boston at the Cambridge School of Ballet. He furthered his studies overseas at the London School of Contemporary Dance. While there, Byrd realized he wanted to pursue the art form professionally. From London, Byrd traveled back to New York City to begin what would become an illustrious dance career, performing with the likes of Kathryn Posin, Gus Solomons, Jr., and Twyla Tharp, among others.

In 1976, during a Los Angeles tour with Solomons, Byrd discovered a new avenue for his artistry – choreography. Here, he choreographed for the first time on the dance department at the California Institute of Arts, where Solomons was the Dean of Dance. When remembering this initial process and the audience’s enthusiastic reception, Byrd says, “I was hooked from that moment on.” Two years later, he started Donald Byrd/The Group in New York City. Then, in December of 2002, he moved cross-country to take the artistic reigns of Spectrum.

Under his artistic leadership, the 30-year-old company is setting new standards for Seattle’s dance community. In a city where the majority of contemporary dance work is project-based, Spectrum employs its dancers for a full season—the length of contract varies each year, but the 2012/2013 season is 36 weeks. Currently, Spectrum is the second largest dance company in the state of Washington, second only to the Pacific Northwest Ballet.

Spectrum primarily dances Byrd’s work—it made the most financial sense when he first took over the company. The repertoire can sometimes comment on polarizing social issues, but mostly it is about creating a theatric experience. “We ask the audience to be a decision maker in the process,” says Byrd, who is always looking for ways to pull the audience into Spectrum’s powerful world. “The work that I do is about the need to communicate, the passion to explore and ask questions.” He further asserts that Spectrum is always pushing for more, bigger movement and a bigger impact. “I try not to settle.”

Spectrum primarily dances Byrd’s work—it made the most financial sense when he first took over the company. The repertoire can sometimes comment on polarizing social issues, but mostly it is about creating a theatric experience. “We ask the audience to be a decision maker in the process,” says Byrd, who is always looking for ways to pull the audience into Spectrum’s powerful world. “The work that I do is about the need to communicate, the passion to explore and ask questions.” He further asserts that Spectrum is always pushing for more, bigger movement and a bigger impact. “I try not to settle.”

These aspirations transcend down to his artists. He’s been told that, “the dancers of Spectrum dance as if their lives, their mothers’ lives, their fathers’ lives, their grandmothers’ lives, [and so on] depend on it.” It’s a statement he doesn’t refute and regards as a compliment. Well-trained and with tremendous kinetic intuition, the dancers of Spectrum are artists and athletes who possess an irrefutable commitment to what they do. Careful to not define them specifically as fearless, Byrd says, “ [the dancers of Spectrum] aren’t stuck. They are curious about exploring different ways, trying different things, and have the ability to do things in spite of fear.” By putting their full faith in Byrd and the creative process, the company can push the parameters of the art form.

Organizationally, Spectrum has become a well-oiled, multi-faceted machine with a full time artistic and administrative staff. In addition to the professional company, it has a school with an open division, structured youth programs, and a professional track, providing diverse and quality dance education from a faculty of established professionals.

Spectrum Dance Theater

Additionally, Spectrum strives to educate Seattle’s non-dance community about contemporary dance. Byrd expresses that gaining awareness is one of the company’s biggest challenges, and it’s an ongoing process. He says, “Some of the choreography doesn’t always conform to what people think dance is, so it takes educating them about contemporary dance.” Therefore, Spectrum focuses on finding more ways to put the company in front of the general public. “The more exposure the better [the public] understands.”

As Byrd reaches his tenure with the company, he looks forward to the future with positivity and envisions Spectrum becoming an international dance staple. He’s presenting the board with a wish-list of items, including more national and international touring – Byrd focused his initial years as director on creating a stronger presence in Seattle, growing the company roster from ten dancers to fifteen with four apprentices, raising the dancers’ salaries, and continuing to bring in new choreographic talent.

While budget is always on the forefront of everyone’s minds, Byrd emphasizes, “You have to do more to earn more.” He wants Spectrum to appeal to dancers both artistically and logistically, rationalizing, “If you are going to have high-level dancers, you need to offer them something that allows them to commit to what they do.” And, eventually, he wants the world to know and experience the company’s immense talent and dynamic repertoire.

Photos courtesy of Spectrum Dance Theater.