Ellie Caulkins Opera House, Denver CO

March 2 2013

By Jane Elliot.

On Saturday, March 2, 2013, Denver’s Colorado Ballet presented a mixed bill program titled Ballet Masterworks. The program was a belated Valentine to ballet, cherishing the dance innovators of the past and celebrating the dance innovators of the present; it encapsulated the works of some of ballet’s most renown choreographers, including the legendary George Balanchine, contemporary ballet pioneer Glen Tetley, and the highly sought after American choreographer Val Caniparoli.

The company started the evening off strong, attacking George Balanchine’s technically ferocious ballet Theme and Variations with aplomb. It was, and still is, a ballet full of pomp and circumstance: tutus, tiaras, chandeliers, a regal air of confidence in every demanding step, and a distinct ranking between the ballet’s corps, soloists, and principal couple. Yet, despite all of this formality, Theme and Variations was not just another ‘tutu-ballet’. Balanchine took all of these tools, which were so frequently identified with the art form, and still managed to push the limits of the classical ballet vocabulary. He utilized his trademark intertwining, eye-pleasing patterns and fast, intricate pointe work, which was executed particularly well by the four female demi-soloists (Dana Benton, Asuka Sasaki, Shelby Dyer, and Caitlin Valentine-Ellis).

Colorado Ballet presents Balanchine’s ‘Theme and Variations’. Photo by Mike Watson.

Where the ballet did slightly lack was in the chemistry between its principal couple, Maria Mosina and Alexei Tyukov. Both proved they had the technical chops to plow through the ballet’s challenging and brisk choreography. However, at times, their faces showed the effort. Unfortunately, they were not alone in this performance quality and they didn’t seem to use either the music or each other as a driving force through their pas de deux. While the music called for more expansion, tempting them to luxuriate in a pose a second longer, both Tyukov and Mosina seemed more concerned with the technical execution of each step.

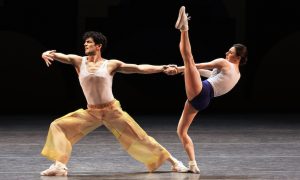

Next on the program was Caniparoli’s ballet In Pieces, which received its world premiere on February 22, 2013. A plot-less ballet that exhibited shifting temperaments from dark and brooding to coy and playful, it personified its simplistic title in that the ballet felt like several pieces strung together to make a whole. At times, the ballet was interesting and engaging (the audience gave it a very warm response), but ultimately, there was a disconnect between all of the ballet’s elements.

The difficulty of being original looms over every choreographer, but with hips thrust forward and classical positions manipulated by a turned in leg or contemporary arm gesture, Caniparoli’s piece felt particularly like ballet déjà vu. Moments of the ballet were even reminiscent of Christopher Wheeldon’s 2006 work for the New York City Ballet, Evenfall, including a duplicate movement of the ballerina bent forward while on her pointes to display the curvature of her modern tutu.

While the costumes seemed to play an integral role in the ballet, the artistic choice of putting the three men in tutu-like garbs was a slight detriment, often softening the men’s dramatic and masculine movements. Perhaps Caniparoli was playing with the idea of unisex notions with the costumes, yet the dancing seemed to present rather definitive male/female roles.

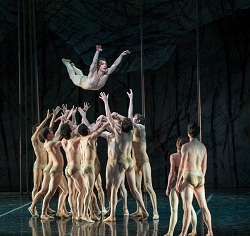

Colorado Ballet presents Glen Tetley’s Rite of Spring. Photo by Mike Watson.

Yet, the movement was danced superbly by all six dancers. Valentine-Ellis appeared to have no bones in her body as she undulated through her torso and sent ripples through her long arms; Dmitry Trubchanov took command of the stage; Christopher Ellis and Sharon Wehner were a pleasure to watch in their buoyant duet; and Jesse Marks and Chandra Kuykendall showed technical mastery in a series of difficult and inventive partnered moves. Additionally, the lighting by Lloyd Sobel had numerous stunning moments, including dramatic silhouettes that highlighted the dancers’ lean, muscular physiques and clean, balletic lines.

The evening rounded out with Tetley’s re-imagination of the iconic ballet Rite of Spring. His interpretation was vastly different than other notable versions (Nijinsky, Léonide Massine, Pina Bausch, among others). It was significantly pared down from the cumbersome costumes and Russian tribal tones of Nijinsky’s original ballet and most notably, the ballet was dominated by masculinity; this included an ensemble of scantly clad men and the role of the Chosen One was danced by a male (soloist Adam Still). These changes gave the ballet a different sense of theatrics and tone.

Originally premiered in 1974, the essence of its era is apparent in the choreography and costumes. But the ballet and Stravinsky’s score still felt poignant in 2013. Led by Adam Flatt, the Colorado Ballet Orchestra played the music brilliantly. And the movement was highly musical, capturing the score’s intense percussion and depth. A few dancers appeared to struggle with some of the floor work, but for the most part, both the male and female ensemble were strong and responsive to the driving music and themes.

The evening was successful in blending many elements of the balletic spectrum. This melding of styles, eras, and choreographers seemed to go over well with the audience, who clearly supported the mission and vision of the more than 50-year-old ballet company. Hearing the oohs, ahs, and bravos from the patrons was a reassurance that ballet is not a dying art form, but continues to inspire, entertain, and spark conversation.

Photo (top): Colorado Ballet presents In Pieces by Val Caniparoli. Photo by Mike Watson