By Kathleen Wessel.

Teachers, think of the last time someone asked you, “What is modern dance?” Your answer probably didn’t come easy, because most people – even those who teach it – can’t accurately define this ever-changing art form. Once, I overheard an audience member explain to her companion at a mixed-repertory dance concert: “When their feet are pointed, it’s ballet. When they’re flexed, it’s modern.” If only the distinction were that simple.

We can easily identify a definition (and there are many) that is either too narrow or completely wrong. “Free-flowing,” “less strict or demanding than ballet,” “emotionally expressive,” “interpretive”: all can be proved incomplete or inaccurate by calling up historical and current examples. Anyone who has survived a grueling floor warm-up based on the teachings of legendary choreographer Martha Graham knows that “free-flowing” and “loose” were not part of her vocabulary. And one could argue that the highly specific choreography of the late Merce Cunningham, a pioneer of the avant-garde, postmodern dance movement, is in fact more strict than ballet. In keeping with artistic trends of his time, Cunningham certainly did not intend for his work to express an emotion or interpret a story through movement.

At every turn, we run into a movement or choreographic style that defies convention and challenges our definition of modern dance. Some teachers delineate a difference between “modern” and “contemporary” dance under the assumption that “modern” refers to techniques of the past, while “contemporary” choreography is more current. Both terms, as they are synonymous and equally nondescript, fail to categorize this mysterious art form.

This begs the obvious question: as teachers, how do we effectively communicate an artistic genre’s ideals, proper techniques and philosophies if we can’t define it? For a possible answer, we turn to those who have established their own definitions and created a movement language or specific technique that drives their choreographic style. Instead of categorizing this shape-shifting art form, we can study and teach the many traditions – both historical and current – that continue to redefine it.

Here are a few past and present pioneers who have paved the way for the richly diverse landscape of 21st century dance. Talk about these legendary figures in class. Perhaps they will inspire a young student to one day create his or her own movement language.

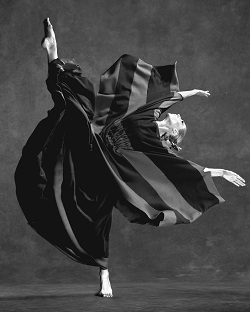

Katherine Crockett, Principal dancer of Martha Graham Dance Company in ‘Cave of the Heart’. Photo © Albert Watson, 2010

Martha Graham’s Contraction and Release

Talk to students about Graham’s focus on the core. With the incorporation of Pilates and the emphasis on core strength in many of today’s dance studios, students should already have some core awareness and be able to isolate it. Practice breathing exercises that encourage students to draw in or “contract” their core muscles, then “release” them. Discuss Graham’s belief that the core is also the emotional center of the body. Her famous philosophy “movement never lies” can resonate with students working on performance technique.

Doris Humphrey’s Fall and Recovery and Jose Limon’s Breath and Weight

Students might be interested to know that these two legendary choreographers worked together – Humphrey as artistic director of Limon’s company from 1946 to 1958 – and collaborated to create a unique aesthetic quality. Many students have probably heard the terms “grounded” and “weighted” to describe modern dance. Humphrey and Limon were pioneers in the effort to teach these qualities. Torso or “drop” swings are classic examples of Humphrey’s fall and recovery technique. Have students work on this concept by emphasizing the breath, while performing any movement with an element of suspension, such as leg swings or falls to the floor.

Atlanta Ballet performing Ohad Naharin’s ‘Minus 16’. Photo by C. McCullers

Ohad Naharin’s Gaga Technique

Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin developed, and continues to develop, this improvisational technique as a way for dancers to lose their self-consciousness and move without physical or psychological inhibitions. To incorporate some concepts from Gaga in class, lead a structured improvisation and encourage students to pay attention to physical sensations rather than what a movement “should” look like. Ask the students to “float on water” or have their “spine become a snake.” And cover up the mirror! Naharin says mirrors “spoil the soul and prevent you from getting in touch with the elements and multi-dimensional movements and abstract thinking.” He advises dancers: “Know where you are at all times without looking at yourself. Dance is about sensations, not an image of yourself.” Tell students, as they are improvising, to “perform to all sides of the room.” They’ll gain the confidence to move more fully in three-dimensional space.

The creator of Countertechnique, Dutch choreographer Anouk van Dijk. Photo by Silvia Sztankovits

Anouk Van Dijk’s Countertechnique

This is a new movement system developed by Dutch choreographer Anouk Van Dijk that emphasizes oppositional and continuous movement. Van Dijk says the theory behind Countertechnique is simple: “If you’re in motion, your movement has direction.” And movement in one direction requires movement in the opposite direction. As students work on a known phrase, have them identify not the primary movements, but the opposing actions or body parts. For example, instead of thinking about the height of an arabesque, have them concentrate on lengthening their torsos. By sending energy and focus to opposing movements, students can create an “ever-changing dynamic balance” and move with explosive power through space.

YouTube is a great resource for viewing examples of these and other techniques. After teaching a class that focuses on historical or current figures in modern dance, encourage students to look up videos or watch clips together as a group. Instead of concentrating on the choreography, have students pay attention to the movement qualities – the how rather than the what. Modern dance is defined and constantly redefined by those who create its language. Introducing the next generation of dancers to the conversation is the best way to keep it going.