By Laura Di Orio of Dance Informa.

One day, dancer Lily Nicole Balogh broke her elbow. One would think it happened during one of her many intense rehearsals or performances, or even during class. It happened, however, after a class, when she ran into a glass door.

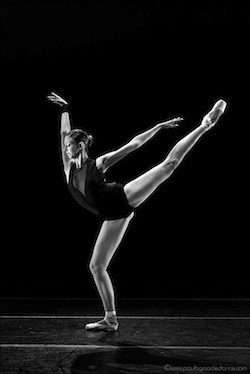

“After a perfectly wonderful, injury-free class, I tripped over thin air and was in a cast for two months,” says Balogh, formerly a New York City Ballet dancer who now works with Ballets with a Twist.

How can this be explained? How can dancers appear so graceful and poised inside the dance studio but often times suddenly turn clumsy and accident-prone in the “real world”?

“I definitely think the adaptations your body takes on when being a full-time, competitive or professional dancer can make you more clumsy if you’re not mindful,” says Monika Volkmar, CSCS, a strength coach and owner/blogger of The Dance Training Project (www.danceproject.ca).

“And of course the stress of the industry can make you less able to control these physiological changes,” she adds. “Do I think that clumsiness is innate in the dancer? My opinion is that it is a combination of genetics, physiological adaptations and mental stress, contributing to varying degrees.”

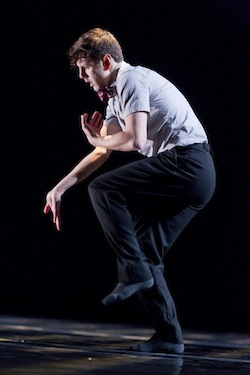

Another self-proclaimed “clumsy” dancer, Kevin J. Shannon of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago says that he has had multiple nicknames due to his “less than graceful” nature – “Shekels” (synonymous at Hubbard Street with “clumsy” or “unaware”), “Mr. Bump” and “Chip.” He says the latter two originated when, as a child, he ran into a wall and also head-butted his brother…accidentally.

“Why I and others I know were originally put into dance classes was in part because we were accident-prone as kids,” Shannon says. “Uncoordinated by birth, I guess.”

So perhaps genetics can play some part in whether or not a dancer can walk down the street without running into someone or something, but Volkmar does seem to believe that a dancer’s learned habits may contribute as well.

Through dance technique, dancers train and develop their “pointed feet muscles,” or plantarflexion. As a result, they use less of, and even lose, much of their dorsiflexion, the flexing of the foot.

“This means that when you swing your foot through when walking, it’s more likely you’ll stub your toe on the ground as compared to someone with ample dorsiflexion,” Volkmar explains. “To compensate, dancers tend to walk with their feet pointing more out to the side to allow for their foot to clear the ground and not trip over it.”

Lily Nicole Balogh, dancer with Ballets with a Twist, here graceful in Mauro Bigonzetti’s ‘La Follia’, has had her bouts of clumsiness outside of the dance studio. Photo by Paul B. Goode.

Balogh adds, “As trained as our bodies are to be some of the most graceful ones in the world, we forget that we train them to dance. We use them in a very specific way inside the studio. Outside the studio, we may become less aware of the importance of control, because walking is supposed to be a piece of cake after fouettés and grand jetés, right?”

And what about dropping things? Volkmar, who even calls herself “butter fingers”, says that another common issue for dancers is thoracic outlet syndrome, a compression of the brachial plexus (armpit/upper ribcage) blood vessels.

“The brachial plexus, which innervates your entire arm, can be compressed at various locations – neck, clavicle, ribs, pectoralis minor – and symptoms of such compression can include impaired dexterity, along with limb weakness, numbness, tingling and other unpleasant feelings associated with local neuropathy,” Volkmar explains.

Dancers, who often carry heavy dance bags, have their arms overhead and repeat movements involving forward-head or drooped shoulders, may be subject to such compression. Nerve compression can happen in the lower body as well, especially in dancers whose legs are strong, and this can result in loss of sensation and motor control, or clumsiness.

While there are valid physiological reasons to explain a dancer’s clumsiness, it may also be attributed to the fact that a dancer’s life can be stressful. Dancers often have a grueling, jam-packed schedule, they often worry about money and they may stress about their appearance or the desire to please everyone watching.

“Perhaps it is that dancers simply appear to be clumsier because of the high expectation society places on them for grace,” Volkmar suggests. “You have to realize that dancers were first, and will always be, people. We’re not perfect. We can’t always be ‘on.’ When we dancers trip, stumble or fumble, it goes against everything we’re trained to do. It surprises people that we’re not as graceful as we ‘should’ be.”

Volkmar offers that maybe dancers’ clumsiness is a result of their “grace-energy” depleting. That is, in the dance studio, dancers work so hard and are able to control their body through even the most complex choreographed movements. Once they step into the “real world,” however, they have an opportunity to not be judged by the way they move, not be watched so intently, that they, probably subconsciously, allow themselves to be clumsy.

“Being judged continuously on the way you move is extremely draining mentally and physically, and so, perhaps being clumsy in the ‘real world’ is the dancer’s way of conserving their ‘grace-energy’ for when it really counts,” Volkmar says. “It’s probably a good thing we take the figurative stick out from our behinds in real life and trip over our own feet once in awhile for our own mental health, and for the sake of our dance performance, too.”

Hubbard Street Dance Chicago dancer Kevin J. Shannon, whose nicknames include “Mr. Bump” and “Chip”, calls himself “clumsy.” Photo by Todd Rosenberg.

Shannon also hypothesizes that clumsiness may happen because dancers are merely dancers, moving around any given space without abandon. In the studio, luckily, there is vastness, with an even, flat surface and no obstacles. In the “real world,” however, dancers must suddenly deal with obstacles: curbs, doors and stationary objects.

“The studio is a dancer’s home,” Shannon says. “Outside in the real world, the landscape is unpredictable and always changing, which is why we knock glasses over practicing port de bras in a kitchen, or spin down the street running into strangers.”

It’s probably a relief for many dancers to know that this clumsiness, whether innate or learned, can be somewhat remedied. Volkmar says that if dancers can train their body to have a more “neutral” alignment, then they may see themselves tripping less and walking with their feet pointed forward rather than turned out.

“I’ve worked on improving the mobility of my ankles so that I can better flex my feet and not trip while walking,” Volkmar says. “I’ve worked on balancing the rotation of my hips to ease the high tonicity of the piriformis and other deep lateral hip rotators. Dancers, with all their turnout, lose a little bit of ability to turn in. I’ve worked on strengthening my upper back and posterior shoulder, as well as being aware of my posture to reduce the nerve compression in my arm.”

Volkmar adds that cross-training and practicing other movement forms – martial arts, yoga, resistance training – can help dancers’ bodies to move smoothly and with control, but not necessarily in “dance mode”.

Volkmar also encourages dancers to consider the mental causes – the stress – of clumsiness, too. “Dancers should work on just slowing down,” she says. “Calm your mind down and your body will follow. Try to remain calm in the rush from rehearsal to work, to finding time to eat, to school. Find ways to reduce stress on a daily basis. Get accustomed to being in the present moment. When I rush, I drop things. Glass things, mostly.”

Balogh believes an aid for clumsiness may be for dancers to train themselves to have a heightened awareness of their actions and surroundings outside the dance studio. “Although,” she admits, “I have made peace with my klutzy self. As long as no more bones are broken, the occasional bruise or bump reminds us that even dancers are human, and it certainly provides cheap entertainment for my family and friends.”

“We’re not perfect!” Volkmar concludes. “Are we really clumsier than the average person? Or are the expectations just higher for us? Could these expectations to not be clumsy be making us even more clumsy? A sort of performance anxiety? As always, the answer is probably a little bit of everything.”

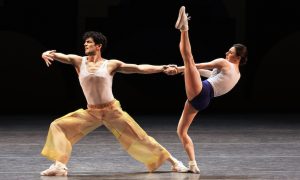

Photo (top): Monika Volkmar, a strength coach, says that clumsiness may be a result of a combination of genetics, physiological adaptations and stress. Photo by Heather Bedell.

Pingback: Dance Injury Prevention - cuts, bruises and blisters | Dance Informa Magazine