By Kathleen Wessel of Dance Informa.

Israeli filmmaker Tomer Heymann admits he doesn’t have a love-at-first-sight relationship with dance. Before seeing the Batsheva Dance Company perform in 1990, he says he assumed the art form was old-fashioned and boring, holding little emotional weight. “I thought it was something my grandfather would go to, and I would never join him,” he jokes. Ohad Naharin’s Kyr – which features a wild take on a traditional Jewish song – changed that perspective. “It was a revolution,” he says of the work, “no one knew what to do afterwards.” Dance, he realized, can be an emotional experience, not just an intellectual one, and it can initiate an honest dialogue between audience and performers. Over the two-week run, Heymann says he saw Kyr “10 to 20 times.”

“When art hits you, you don’t need to understand it or explain. I felt it in my body.” He equates the experience, and his relationship to Naharin’s body of work since, to a natural tattoo; the choreography, he says, lives “inside of me, on me, with me.”

Photo by Gadi Dagon, house photographer of the Batsheva Dance Company.

That deep connection to Naharin’s work brought Heymann to approach the legendary choreographer with an audacious request: to film in the Batsheva studios and make a documentary. At first, Naharin refused. Gaga, the now famous movement language he created and uses to train his Batsheva dancers, requires an environment of total non-judgment; no mirrors, observers or late-comers are allowed in the room, and the experience is highly personal. When Heymann pitched the project, Naharin told him, “Why should I destroy the joy of what I believe is dance? The whole beauty behind it is that it vanishes. Tomorrow, it won’t be the same.”

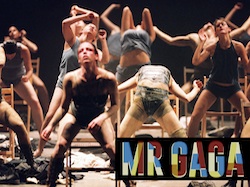

But Heymann was not to be deterred, and on October 7, 2007 (note that he remembers the date exactly), he walked into the studio with his camera and began work on the film he has since titled Mr. Gaga. A clever play on the household name Lady Gaga, the title suggests a certain air of defiance, a sort of trump card played by the man who first coined the term.

Interestingly, and because Naharin doesn’t publicly address or seem bothered by the namesake, the title seems to reflect Heymann’s protective feelings for a movement language that has featured so prominently in his life. Two years ago, Heymann separated from his longtime partner and entered a state of profound depression. “I was completely broken,” he says. “I felt I didn’t have anything to offer to the world.” He didn’t leave his Tel Aviv apartment for three months, and friends began to worry.

Frame pulled from footage of ‘Mr. Gaga.’ Photo courtesy of Vadim Dumesh.

The details are fuzzy, but Heymann says he ended up on the phone with Naharin and admitted, “Ohad, I’m no good.” Naharin didn’t know about the separation but recognized something in his tone and invited Heymann to a Gaga class. Heymann had little expectation, but went because he felt he had nothing left to lose. “I walked very slowly,” he says, “I was embarrassed to go, ashamed of my body and how I move.”

“What I found was amazing,” he says. In Gaga/People, a class reserved for non-dancers, no one judged him or cared what he was doing. Surrounded by people of all ages, backgrounds and body types, Heymann realized no one is perfect. When he left, the world – streets, houses, the sky – looked different. “I was alive again,” he says. And though Gaga didn’t prove to be a miracle drug, it opened a door; it helped him come up “from the basement and discover a little light from the window,” even to open it, “smile, and see the beauty outside.”

Frame pulled from footage of ‘Mr. Gaga.’ Photo courtesy of Vadim Dumesh.

After that experience, Heymann became a regular Gaga practitioner and began to wonder how he would capture the complicated physical and emotional experience on film. On tour with Naharin and Batsheva in Helsinki, the filmmaker and choreographer sat down to hash out the details. The meeting turned into an eight-hour discussion of Naharin’s personal history and the severe back injury that forced him to discover new ways of moving. Naharin discussed his exploration, both in Gaga and his choreography, of the “connection between pleasure and pain,” an idea Heymann believes is universal and deserves recognition. “People might look at Gaga as a stranger, but [the movie] will make them see it as family. A family of people who want to move and want to discover something about their bodies.”

Heymann Brothers Films, the production company Tomer and his brother Barak formed, has released a series of teaser videos as part of a massive Kickstarter campaign to fund the ambitious Mr. Gaga. In one studio shot, we see Naharin’s young daughter calling for her mother, Batsheva dancer and Naharin’s wife Eri Nakamura. Nakamura is clearly pained, attempts to keep dancing, then grabs her bag and leaves rehearsal. The scene is emotionally charged and fascinating, offering a shockingly intimate glimpse into Naharin’s psyche.

Frame pulled from footage of ‘Mr. Gaga.’ Photo courtesy of Vadim Dumesh.

“There is a very high level of conflict between these two mediums,” Heymann says of cinema and dance. “Ohad’s dance refuses to be frozen, and I come with my refrigerator to freeze it because I want everyone to see it later, because it’s a beautiful moment.” But he says his intention with the film is not to explain or decipher Naharin’s complicated rehearsal process, he simply documents then allows viewers to see connections for themselves.

He sees the film as a tool viewers can use to enter and read Naharin’s work from a new place of understanding. Mr. Gaga, he says, will be “the secret behind the creation,” a gift to those who know and those who will see Naharin’s work. It is “a love letter to dance” written by someone from the outside world.

Photo (top): Ohad Naharin leads a dance class. The image is pulled from footage of Mr. Gaga. Photo courtesy of Vadim Dumesh.