By Mary Callahan of Dance Informa.

I have recently been reading Ann Wagner’s Adversaries of Dance, a well-researched exposé documenting the history of anti-dance law, literature, and libel in the United States from the time of the Puritans to the present. It’s comical—the notion that a country could grow so distraught over what now seem the tamest and most timeless of dances: the waltz, the polka, the Lindy Hop. Adversaries criticized the immorality of dance—both the idea that dance was a purely physical (and therefore evil) act with no intellectual or ethical capacity and the assumption that dance hall culture encouraged the consumption of alcohol and the promiscuity of young people.

But dance (and anti-dance theory) in nearly four hundred-year old America has not simply lasted; it has evolved. Throughout our history, dance opponents have argued that whether for the stage or social function, whether with a partner or without, dance—the pleasurability and expressionism in moving one’s body to music—is the road to all evil. We can see this in classic Hollywood dance films: the rules of segregated dancing in “Hairspray,” the anti-dance lawmaking in “Footloose,” and the conscientious parents in “Dirty Dancing.” As a professional dancer, a liberal thinker, and a proud feminist, I never imagined that I would become one of those adversaries of dance.

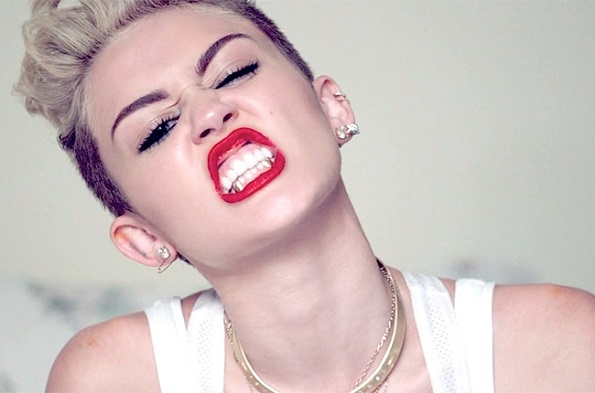

This perplexing epiphany occurred last June when teenybopper turned troublemaker, Miley Cyrus, released her long-awaited single, “We Can’t Stop.” While I had no interest in wasting four minutes of my young life watching her music video, the link quickly began to flood my Facebook newsfeed. I finally gave in. I sat at my desk on that scorching New York City summer afternoon with the air conditioner on full blast. As the Vevo video loaded I noticed the bottom right corner of the screen: over nine million hits in under twenty-four hours.

Dancers Michael and Nadiah on SYTCYD Australia perform a “twerking” dance to Busta Rhymes and Nicki Minaj’s ‘Twerk It’, choreographed by Tiana Canterbury, on March 2 2014 . The idea of a “twerking” dance was not well received by the judges. Photo copyright Shine Australia 2014.

Before the beat even drops I hear a base-like chant, “It’s our party we can do what we want.” Miley appears, slicking-back her platinum Mohawk hair, wearing a white skin-tight crop top and leggings, and framing her mouth with ruby red lipstick. Oh, she also adorns a gold grill on her bottom teeth. I sit and watch—eyes unblinking, brow furrowed, mouth slightly ajar. At first glance “We Can’t Stop” is a mash-up of gigantic teddy bears, yogurt-filled fingers, a French-fry face, after-dark pool parties, lots of white bread, taxidermic animals, alphabet soup, and a talking face animation reminiscent of the Phantom of the Opera. Oh, and the most degrading dancing I have ever seen.

Midway through the video Miley sings, “To my home girls here with the big butts, shaking it like we at a strip club, remember only God can judge us, forget the haters ‘cuz somebody loves ‘ya.” In her revealing white workout wear, Miley dances with three voluptuous African American women. From an informative bowl of alphabet soup, we learn that the four are “twerking.” Cyrus hinges forward at the waist with her torso perpendicular to her straight spread legs. Facing her…derrière…either to that of another dancer or directly to the camera, she rapidly oscillates her hips back and forth, rhythmically gyrating the fleshiness of her posterior. Oh, and she also sticks her tongue out.

Twerking has taken the nation by storm. But really, the origins of twerking seem to have evolved from traditional African Mapouka and Middle Eastern belly dance. This style was revered by such cultures and performed at social and religious events. While Miley didn’t invent the latest booty-shaking craze, her “We Can’t Stop” music video and VMA performance certainly helped to skyrocket its notoriety in the United States. Less than two months after Vevo’s release of “We Can’t Stop,” the Oxford Dictionary officially added “twerk” to the American English language. “Twerk, v.: dance to popular music in a sexually provocative manner involving thrusting hip movements and a low, squatting stance.”

But let’s pause here for a moment and take a look back at Wagner’s Adversaries of Dance. She describes that in 1877 American journalist Ambrose Bierce published The Dance of Death, arguing, “the modern waltz is not merely ‘suggestive’ . . . but an open shameless gratification of sexual desire and a cooler of burning lust.” In the nineteenth century, dance adversaries like Bierce condemned the waltz as immoral and unsafe due its “closed” dance position, brisk tempo, and constant twirling choreography. What horror to think of what this sort of dancing might possibly lead to…shorter dresses that reveal a lady’s ankles, and riotous music. In ruminating over this, I can’t help but wonder: is twerking the modern day waltz?

Now, I guess I’ll admit that I’m kind of a prude. I didn’t try alcohol until I turned twenty-one, I find cursing repulsive, and I get embarrassed changing in the ladies’ locker room at the gym. But I pride myself on my prudence. If I’m angry, I think there’s a much better way of articulating myself than blurting out a word that translates to “a pile of feces.” I’m not going to say that I’m not judgmental. I certainly am. But I believe I am careful to shape my opinions and judgments based on thoughtful reasoning. So, when I had such a traumatic reaction to the new twerking sensation glorified in Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop” video, I wanted to understand why.

In August The Huffington Post’s Bonnie Fuller praised Miley’s new music video as a “high-spirited celebration of the freedom that young women are blessed with today to fully explore and celebrate their sexuality” (Fuller). Are you kidding me? If Miley Cyrus is hailed as a modern day feminist, we have a problem. Or maybe I have the problem. I sort of laugh at those 1950s suburban goody-goodies who feared that the music of Elvis Presley and Little Richard promoted sex and juvenile delinquency. But in feeling so offended and angry in response to Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop,” have I become one of those conservative critics that future generations will later scoff as sententious? Am I some sort of old-fashioned prig to criticize this contemporary depiction of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll?

A scene from the ‘Twerk It’ music video by Nicki Minaj and Busta Rhymes. Photo source: www.rap-up.com

I feel strangely stuck—stuck between Bierce’s criticism of immoral dancing and Fuller’s definition of what it means to be a feminist. You might think that this gap in which I feel “stuck” is fairly large—nearly one hundred and fifty years large. But I cannot seem to negotiate the professional dancer, liberal thinker, and proud feminist within me. I try to argue myself out of this. Twerking blatantly objectifies women and I therefore have every right to be offended. But then again, dance critic Ann Daly illustrated how Balanchine’s ballets do the same, rendering the ballerina as a delicate, sensual, and ethereal prop to be manipulated by the male dancer.

While I have always been pretty outspoken, I think my feminist streak really began during my freshman year—or rather, first year—at Scripps College. Applying to a super small all-women’s liberal arts college, I carefully constructed my admissions essay about freeing myself from a similar situation of feeling “stuck:” stuck between my dream of becoming a Radio City Rockette and my self-declaration as a feminist. It’s because of those generations of strong women before me, I reasoned, that I now have the freedom to be whoever I want to be—I can embrace my fervent intellectual side without denying über feminine self, too. But that was four years ago, and just figuring a way to negotiate the conflict of interest that bothered my conscience. This twerking phenomenon, however, has really rattled my sense of self. Because it’s really not about “twerking;” it’s about not being able to reason my way out of my frustration.

In order to write this piece, I reluctantly re-watched “We Can’t Stop.” And again I felt the same queasiness brewing inside of my stomach, the same tension attacking my forehead, and the same resentment burning within my soul. As I sit and stare at my laptop screen, I keep hoping that a solution will pop into my brain, zip through my nerves to my fingertips on the keypad, and relieve me of my “stuck-ness.” But I’ve got nothing. However, as much as it pains me to end this piece without a real conclusion, perhaps that’s the right way to go. Over my four years of college, despite all of the exams and graded papers, the greatest thing I have learned is that I do not need to know all the right answers. While I am graded on paper, the real challenge is to evaluate myself—to question my own beliefs and have the resilience to admit I am wrong and change my mind. If you fall in quicksand, the worst thing to do is frantically try to wrestle yourself out. You have to relax, move slowly, and actually embrace the muddy sinking feeling in order to get unstuck. So here I am, embracing my “stuck-ness,” confident that one day I, too, will discover a way to rise above it: “Hello. My name is Mary and I am a dancer. Oh, I am also an adversary of dance.”

Photo (top): A scene from Miley Cyrus’ “We Can’t Stop” music video. Source: Billboard.com. www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop-shop/1567360/miley-cyrus-we-cant-stop-video-is-completely-insane-watch