By Laura Di Orio of Dance Informa.

People who photograph dance have a keen eye for beauty, movement, lighting and timing. They must often develop a precision to capture dynamic shapes, an impressive lift or a floating turn. So it seems to make sense that some of the best dance photographers were once dancers themselves. They have a clear understanding of movement when taking photos of stage work, and they know what to ask of dancers when shooting them in a studio. The path from dancer to dance photographer seems to be a natural one. Some switch to the behind-the-lens career after their dance career. Others complement their lifestyle with photography while still continuing to dance. Here, Dance Informa looks at three dancers-turned-photographers’ stories.

Rachel Neville: Picture-Maker

www.rachelneville.com

Dance photographer Rachel Neville was a classically trained youngster who, like many students her age, would gush over the pictures in various dance magazines. But besides admiring the pretty lines of whoever was featured on the cover, Neville became aware of the photographer’s name as well. She continued studying dance, however, and moved to France at the age of 18 to train before dancing professionally in Germany. A knee injury brought her back to her homeland of Canada, and this leave from dance pushed her to go back to school. It was then that she got her first lesson in photography.

“I had to finish high school and went to an alternative program that allowed self-directed study,” Neville explains. “The grade 13 art course I took happened to be photography, and that was it.”

Photographer Rachel Neville loves ‘making pictures’. Photo by Rachel Neville Photography.

From there, she went on to study at Humber College in Toronto, where she graduated in 2000 at the top of her class. In college, she actually became increasingly interested in food photography and loved moving things around and lighting them in a way that pleased her eyes. She started shooting some dance but never dreamed that that would be her future. With not much dance work available to her in Canada, Neville went into wedding and commercial work photography and did what dance work came her way.

In 2006, however, when she moved to New York City, she decided to pursue dance photography further. Starting fresh in a new career and in a new place would prove to be a challenge, but she took it on just as she says a trained dancer would: with passion and attack.

“I had an advantage and a disadvantage from the start,” Neville says of her NYC move. “I had some pretty good technical skills and a body of work already, but as a total outsider I didn’t have a network of friends or any relationships to build off of. So building a network was and still remains the hardest thing for me.”

Soon enough, however, Neville’s dance photography career began to take off. Today, she can say she has had her work published in The New Yorker, Dance Magazine and Pointe Magazine, and she has shot for Grishko, Dance Theatre of Harlem, Ajukun Ballet Theatre, Jansuphere, Dance Iquail, Ellison Ballet and more.

She claims her specialty is in individual dancer head and body shots, as well as shooting for company marketing materials. “My true love is of ‘making’ pictures as opposed to capturing moments,” she says.

Photographer Matthew Murphy at work. Photo courtesy of Matthew Murphy.

Neville takes pride in skills she has acquired from her dance background that may give her a one-up on being a photographer of dance. She understands things like timing and what makes a good line or shape, and she understands what type of lighting is most flattering for dancers. She also knows how to take alignment and movement that is 3D and shift it into 2D.

“But probably most important in my background is my teaching,” Neville adds. “I know most of my clients are able to feel fully at ease and at their best because I am able to coach them into looking their absolute best. Like most of the dancers I work with, I’m a little perfectionist.”

Neville admits the hardest part of her transition from dancer to photographer has been the business aspect and that she sometimes has a hard time going out there to make connections and run the business like a business. So, to dancers who may be interested in pursuing dance photography, she suggests taking business classes or hiring a business coach.

For Neville, being a dance photographer is about seeing the whole package – lines, shapes, music, energy and emotion. “It’s in this next generation of dancers who, I hope, move away from being a slave to the acrobatics and take more steps toward dance’s glory in storytelling, performance quality and energy in stillness, or whatever ‘it’ is for an individual, that that will start to be more and more appreciated in dance images,” she says. “I will continue to push for it with my clients anyway.”

Matthew Murphy: From ABT to The New York Times

www.murphymade.com

Freelance dance and theater photographer Matthew Murphy was a gung-ho, ballet-focused dancer. He comes from a dance family, started training at age 10 and moved from Montana to study at North Carolina School of the Arts when he was 13. He eventually secured a contract with American Ballet Theatre (ABT) Studio Company at 17, moved to New York City and later danced with the main company at ABT for five years.

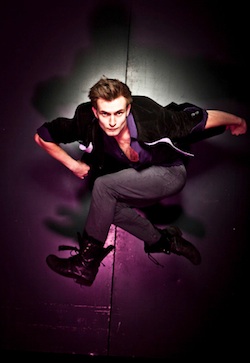

Keigwin + Company dancer in a photo shoot by former dancer-turned-photographer Matthew Murphy. Photo by Murphy Made Photography.

A few months after he turned 21, however, Murphy came down with Chronic Epstein Barr Virus and was unable to dance for two years. To soothe his creative soul, he saved for a Canon 30D camera and started to take pictures around his neighborhood and drop in at rehearsals to photograph the company dancers.

Murphy didn’t acquire any professional schooling in photography, but he says the constant practice and people around him provided great training. “Rosalie O’Connor and Erin Baiano were both dancers from ABT who had made the transition to photography,” he says. “They both encouraged me to keep learning by trial and error.”

His extensive dance background opened the doors for many photography opportunities. “Oddly enough, one of my first jobs as a photographer was very high-profile,” Murphy says. “I was sitting in the audience at New York City Center with my dancer friend David Hallberg one night when the photographer in the row behind us recognized him. She introduced herself as Andrea Mohin from The New York Times, and this little voice in my head chimed in and told me this was a moment I needed to put myself out there. I mentioned I was a new dance photographer, and she suggested I send her my portfolio. The day after, I gathered my strongest images and sent them her way. She was so generous and connected me with an editor at The Times, who brought me in for an interview and hired me as a freelancer with the Arts section. I couldn’t believe my luck.”

In addition, Murphy has since been the production photographer for the Broadway shows Kinky Boots, After Midnight and Rocky, and his work has also appeared in Broadway.com, Dance Teacher and Dance Magazine, among others.

Murphy believes that coming from a dance background has had its advantages. He knows correct technique, understands and follows choreographic patterns and sees how they will time with musicality. In addition, “the perfectionist mentality is a tool you learn as a dancer that will serve you well in any career you follow,” he says.

Also a quality in dancers and one that serves him well in photography is the constant desire to learn and grow. “I think it is extremely important to stay hungry,” Murphy says. “I spend most of my ‘days off’ looking at the work of other photographers and getting inspired.”

In conclusion, Murphy says, “I still get a huge thrill out of shooting live performance. It is incredibly difficult but intensely rewarding. I always feel so spoiled to capture artists at the top of their field.”

Photographer Jaqlin Medlock working with dancers Bryn Cohn, Emily Daly, Rachel Abrahams and Mondo Morales during a Bryn Cohn and Artists photo shoot. Photo courtesy of Jaqlin Medlock.

Jaqlin Medlock: Dance and Photography Double Studies

jaqlinmedlock.com

For as long as Jaqlin Medlock can remember, she has had a dual interest in dance and photography. She has always carried a camera and was always shooting dancers in rehearsal, and for years, she has maintained a strong dance career. Medlock graduated with a BFA in Dance and Photography from Marymount Manhattan College in 2007. She has danced with choreographers Bradley Shelver and Bennyroyce Royon, spent two years with the Steps Repertory Ensemble, danced with DeMa Dance Company, dre.dance and, currently, with Stephen Petronio Company.

After extensive photography studies in both high school and college, Medlock had an itch to learn digital photography. She contacted her favorite dance photographers and landed an internship with well-known dance photographer Eduardo Patino.

When her desire to have a career in studio photography grew, Medlock bought lighting equipment and rented studio space. At the time, she was dancing for the Steps Repertory Ensemble, so she approached them about shooting dancer photographs. The dancers went to Medlock’s rented space, where she took tons of headshots and dance photos, and Steps began using them to advertise for the school. Medlock continues to photograph the Ensemble each year.

“Aside from a couple of postcards, I haven’t really advertised,” Medlock explains. “I get most of my business through friendly recommendations and people liking their friend’s albums on Facebook.”

Kile Hotchkiss and John Eirich of Take Dance in a performance at Peridance Capezio Center/APAP 2014. Photo by Jaqlin Medlock.

Since then, Medlock has filled her resume: covers for Dancer Magazine, advertisements for a Sansha clothing line, studio shots for Marymount Manhattan College and photographs for companies such as Thang Dao Dance Company and CelloPointe, and dance subjects such as ABT’s James Whiteside and tap sensation Jared Grimes. She also photographs live performances at Peridance Capezio Center and each year at the Young Choreographers Festival.

Medlock says her own dance experience has definitely fueled her knowledge as a dance photographer, and vice versa. “I know the common concerns that dancers have – wanting to have longer legs, better feet, look thinner, look taller,” she adds. “My photography career also helps my dance career in the same way. I am always aware of what angles the audience is seeing me from, how to adjust to be more flattering for my own body and, most importantly, am always aware of where my light is when I am on stage.”

Medlock also understands that being a dancer can sometimes be financially difficult and tries to be accommodating in that way. “The hardest part for me is keeping the cost of my photo shoots low enough where they can be affordable,” she says. “I know first-hand what the average dancer makes, and I know how important photos are for a dancer’s career. More times than not, dancers have to spend far more than what they make to get the photos they need. I keep this in mind and try my best to find different ways to solve this problem.”

Photo (top): Rachel Neville works with a young dancer on a shoot. Photo courtesy of Rachel Neville.