By Stephanie Wolf of Dance Informa.

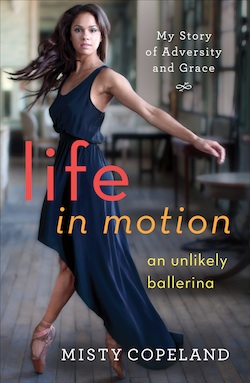

Despite being labeled as a “prodigy” at 13, American Ballet Theatre soloist Misty Copeland’s journey to the top of the ballet world hasn’t been picturesque. In March, the African American ballerina, with legs for days and womanly curves, released her memoir, “Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina.” Her first attempt at published writing — which landed her on The New York Times’ “Best Sellers” list — Copeland talks about overcoming the adversities in her personal life to be successful in a profession that is predominately white and often serves to the upper class echelon of society.

In the beginning, the writing feels sophomoric, making Copeland sound much younger than her 30-plus years. And, some, may argue, the ABT soloist is rather young to publish a book surrounding her life story. However, Copeland has a compelling story to tell, from a family in constant disarray, to a very public legal battle, to making it or breaking it in one of the world’s leading ballet companies. Putting aside critique on word choice or sentence structuring, the storytelling is there, and her writing matures as the book progresses. Any fans of the “unlikely ballerina” will want to read this.

She opens the book with this dedication, “To all ballerinas and dancers of the world. Our art is vital. Let’s keep it alive, growing and expanding.”

Ballet has been struggling to secure its foothold in contemporary culture, but Copeland’s words resonate deeply and set the tone for the 263 pages that follow. She dives into the sacrifices she made for her career, but shows no regrets. Ballet was, and is, Copeland’s salvation, and she happily accepts the responsibility of continuing its relevance.

“I think that this art form is so beautiful,” Copeland tells Dance Informa. “Art, in general, can do so much for us as people and a society. It has allowed me to grow in ways I don’t think would have been possible without it.”

“I think that this art form is so beautiful,” Copeland tells Dance Informa. “Art, in general, can do so much for us as people and a society. It has allowed me to grow in ways I don’t think would have been possible without it.”

While Copeland speaks of journaling since she was 16, she confesses this is the first time she’s tackled writing a book—she adds that the years of journals, a record of her life thus far, were a huge asset in the writing process.

Only in her early 30s, it may feel premature for Copeland to share her saga. However, she says the timing was perfect to open up.

“I knew I would tell my story at some point,” says Copeland. “I must admit I didn’t think it would be this early on. But I thought it was important for me, at this junction in my life, to share my experiences with others, who may be on a similar path as me or who feel that they don’t have the support or opportunities to dream big. My story is universal. I’m aware of the platform I possess, and I’m taking advantage of that.”

A “late bloomer,” so to speak, her progression in ballet hasn’t been conventional and was largely in the public eye — a challenge for one who admits to enervating bouts of shyness and fretfulness.

“I have had an interesting introduction to the world of ballet,” says Copeland. Starting with the local Boys and Girls Club in San Pedro, Calif., she expresses her uncertainty during her introduction to the art form. But her talent caught the eye of the club’s ballet teacher, Cindy Bradley, who asked Copeland to train with her at her school, the San Pedro Dance Center.

Amidst instability with her home life, Copeland talks about taking to ballet, finding her place in the universe through music and movement. At this point, she talks about hearing the word “prodigy” for the first time, a word that follows her throughout much of her training and early career.

Misty Copeland in a photo shoot for Under Armour. Photo by James Michelfelder.

Her prodigy status caught the attention of local news affiliates when she was 13, but her media exposure reached a pinnacle when she sought emancipation from her mother — Copeland was 15 at that time.

Despite this and many other impediments, Copeland shares how she achieves her dreams of dancing with the elite American Ballet Theatre. Yet, when she fulfills this life goal, she finds new struggles and obstacles to overcome within the competitive ranks of ABT.

Here, the book gets stronger in both content and voice, especially when Copeland suffers a back injury that sidelines her for an entire season and costs her the coveted role of Clara in The Nutcracker. She talks about some of the real, harsh realities that face many burgeoning ballerinas: perfectionism, anxiety, a maturing, changing body and, more specific to Copeland, the lack of racial diversity in the profession.

The book becomes immensely more personal and, thus, more interesting. It would be impossible to convey everything the memoir covers in a concise piece of journalism. She succeeds, she fails, she learns and she accepts; all of these moments Copeland retells with the hope to spark dialogue around certain hush, hush topics, rather than to further catapult her own career.

Copeland says reliving some of these experiences was “very cathartic,” and helped her appreciate the influential figures throughout her life and career. She adds, “It’s allowed me to let go of some of the decisions made for me that I had no control of, and to learn from mistakes I’ve made as well.”

As to why she chose the title of the book, Copeland says, “It made perfect sense. My life was in constant motion from the time I was two, and then continually reinventing myself as a dancer and artist.”

Her message is not only heartfelt, but gets the reader thinking about the larger picture of diversity in the arts, particularly in the classical realm. She repeats again and again in the prologue, “This is for the little brown girls.” The echo of this simple mantra propels Copeland through her career, and it helps propel the reader through the book — “this is for the little brown girls.”

Making history as the first African American female soloist at ABT, Copeland continues advocacy work beyond the ballet studios and Metropolitan Opera stage. She’s an ambassador for the Boys and Girls Clubs of America’s Youth of the Year program, and helped spearhead Project Plié, a diversity initiative through ABT and BGC. Copeland has also given a TEDxGeorgetown talk about ballet’s relevancy to the world, and says she takes every opportunity to speak to kids about achieving what may seem impossible.

Copeland writes, “Picture a ballerina in a tutu and toes shoes. What does she look like?”

Sure, many may conjure up images of the ideal white swan, or a sylph with milky white skin and large doe eyes. But it only takes seeing Copeland onstage once to debunk that harsh stereotype and realize this is what American ballet is about: power, beauty, grace and diversity… no matter skin color or physique.

Top photo and book cover photography by Gregg Delman.