Miller Theatre, Columbia University, NYC

January 17, 2015

By Leigh Schanfein of Dance Informa.

On a cold winter night in the beautiful but modest Miller Theatre at Columbia University, the audience surrounding me seemed a veritable who’s who of the New York City chamber ballet scene in the upper center balcony, pushing the cast’s friends and late arrivals to the back of the house. Honestly, that’s probably where they are used to finding empty seats seeing as how these friends happen to be a handful of principals from American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet who usually watch their friends from the wings. Not a shabby crowd for your opening night.

Before the show, I asked my educated balletomane-viewing companion for a one-word opinion of each piece to see if we felt the same way about the work. In the name of fun, she agreed and the night began. The artistic director, Craig Salstein, addressed the audience at the top of the show with short remarks on Intermezzo’s emphasis on collaboration and new work. In addition to the choreography that was either new for this show or created earlier in the season, the piece by Salstein was set to commissioned original music by Patrick Soluri, and all of the works had an associated piece of artwork inspired by the dance hanging in the theater lobby. The emphasis on collaborating with choreographers is upheld with the decision that this will not be a repertory company since new works will be created each season, which is very fortunate since this season’s works are a mixed bag, some delightful and some not so.

The show started off at a low point but continued to get relatively better in the second part of the evening. Unfortunately the low point was Salstein’s own The Myth of Sisyphus, based on an essay on the myth by Albert Camus, and the myth itself, in four parts. The choreography was repetitive but not in a meditative, contemplative, hyper-repetitive abstraction. It was almost entirely frontal and monotone in tempo, space and energy; the dancers’ faces as monotone as the lack of dynamicism in the steps. The only part that was not lacking in emotion and also used multiple dimensions was a short passage where one dancer would push the rotating circle of dancers laboriously as if all of the dancers are the rock and all of the dancers are the pusher, a very simple metaphor shown simply and well. The dancers were strong and steady. New York City Ballet’s Abi Stafford was positioned to be a leader in a piece with no lead. My viewing companion chose the words “rigid” quickly followed by “unimaginative” to describe the work.

The second piece of the night should have been the opener for its energetic pounce and extremely short duration. Mythology was choreographed by Gemma Bond, a current corps member of American Ballet Theatre, and reflected the tale of the Trojan Horse. This was one of the rare occasions when black leotard and black tights helped neither clarity of movement nor the dancers with the cleanliness of their lines. Slight differences in timing and angularity gave the piece an overall dusting of messiness and ever so slightly disconcerting feeling that detracted from the strong and swift choreography. To wit, American Ballet Theatre corps dancer Nicole Graniero stood out not for her role but for the strength of her line in a sometimes-cacophonic grand allegro. My viewing companion’s one-word take on the decidedly short piece was “pulsing” for its unrelenting, driven choreography.

Just after an emotionally restorative intermission, Cherylyn Lavagnino’s Hera’s Wrath graced the stage with new breath. Lavagnino’s maturity and experience as a choreographer were evident in the elegant and tumultuous choreography placing the adulterous couple in the sights of the betrayed queen, who thus seeks her revenge. Temple Kemezis was nearly ethereal in her grace even though she portrayed the sole mortal, while Alfredo Solivan appeared her very trustworthy partner. It would have been nice to see more character from Solivan to match that effusing from Kemezis and Rina Barrantes’ forceful Hera. The urgency and slight trepidation of the couple made me believe in the fearful joy of her naive love, and Hera’s pain and anger came through in Barrantes’ solid and graceful bearing. The female duet effectively parlayed the music in the name of the story, and the costumes were the first excellent choice of the evening. My companion described it at “vivacious” for the women.

Two former New York City Ballet dancers came together for Black is the Colour of my True Love’s Hair, with themes from Oedipus, performed by Kaitlyn Gilliland and choreographed by Adam Hendrickson. Gilliland had previously performed Hendrickson’s choreography with Intermezzo in 2013. He must like her legs like we do since she is a dancer who uses the full length of hers in every move. The first part of the piece, which was the only one of the evening in soft shoes rather than pointes, felt as though it had been choreographed in a small room with a slippery floor. Not quite satisfying changes in direction felt shortened rather than counterbalanced and passages stopped before their time. Perhaps this was on purpose and owing to Oedipus being confined to a prophecy, but I didn’t get that feeling. The second part of the piece fell into place with very direct but effective gestures and movement that appeared to truly use the space even when stationary. Gilliland, too, seemed to find a nice freedom in her character with the musical and choreographic change. The second and more satisfying half of the piece inspired my friend to describe it with “chutzpah,” of which Gilliland must have a lot.

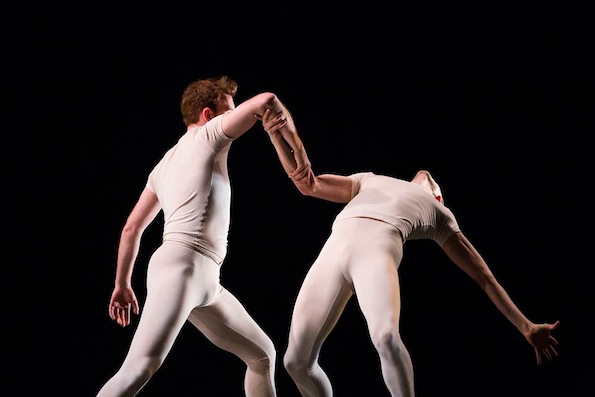

The last and most exciting piece on the program was Journey to Pandora by Ja’Malik, based on a mixture of mythologies. The piece was exciting not just in its tempo but also for its use of excellent lighting, interesting and sensical spacial structure, sharing of the stage time amongst the cast, and the Apollonian sensibility of the choreography. The neoclassical choreographic elements were balanced nicely with more contemporary work that did not completely stray from balletic form. In the middle of group work with the excellent women (Giselle Alvarez, Rina Barrantes, Nicole Graniero and Nancy Richer) and a stunning, perhaps remorseful or foreboding solo by Graniero, was a men’s duet, beautifully carved into space and playful with time. Ja’Malik did an impressive job creating a classical duet with some partnering elements between two men that fit justly within the themes of the piece.

Unfortunately, it must be mentioned in the review of this particular performance of this work that the brilliance of the piece and its largely exuberant and talented dancers was affected by the unbelievably uncomfortable facial expression and demeanor of one of the male dancers. I found out afterwards, however, that he was performing with two fractured metatarsals, so leniency is deserved! His perseverance and commitment to keep dancing must be mentioned. We wish him a speedy and complete recovery.

For the choreography itself, my companion found the work “spritely,” with which I do not entirely agree. Though the work was often sharp and brilliant, it had a much deeper sensation as if the wisdom of the myths were informing the dancers who spoke to us through their gestures.

The show as a whole was unbalanced, but found times to shine by virtue of its dancers and the choreographers, though not always at the same time. I’d argue that none of the pieces really brought us out of myth and into philosophy, but some of the choreographers managed to conjure up the inherent mystery in mythology, reminding us that while the myths present us with joy, pain, villainy and triumph, we must still ask not only what these stories mean but why they endure. In looking to the gods, we learn of man. And in looking to dance, we learn of man too.

Photo (top): Intermezzo Dance Company’s Olivier Swan-Jackson and Morgan Stinnett in Ja’ Malik’s ballet Journey to Pandora at Miller Theatre. Photo by Sarah Sterner.