“Being yourself… It’s not an easy thing to do.”

Jenifer Ringer would know. Having spent 24 years as a member of one of the world’s most respected, iconic ballet companies, she has a thorough understanding of just how easy it can be to lose oneself in the whirlwind of an elite, high-profile career. The closer she grew to the spotlight as a rising star of New York City Ballet in the early 1990s, she recalled in a recent interview, the more she began “to use performing as an escape in an unhealthy way. . .always thinking about it, all day — how I would look, how I would dance. Everything else got pushed aside. I didn’t confront anything in my life that was unpleasant. I made performing too much of a reality.”

Jenifer Ringer Fayette with student Jackson Bradsha. Photo by James Fayette.

In a profession that encourages a certain degree of otherworldliness and the cultivation of seemingly super-human skills, this brand of obsessive thinking is not uncommon and can actually be regarded as an asset. Yet for Ringer, the real ascent to artistic fulfillment — and to some of the most memorable moments of her stage career — began when she became more grounded in her identity beyond the theater. Not until chronic depression and anxiety resulting in a visible up-and-down struggle with weight sidelined her from the ballet for several seasons did she come to an unsettling realization:

“I began to notice that I was one way with my family, another way with people from church, another way with people from the company and my friends,” she admitted. “I started to wonder why I was different with everyone and realized that I wasn’t comfortable with myself . . . I needed to learn how to be a person while still being a dancer, to live in the real world when I stepped off the stage.”

Today, over a year after her final bow as a beloved NYCB principal (and the publishing of her memoir, Dancing Through It: My Journey in the Ballet), Ringer is sharing this lesson in balance with a new audience: her students at the Colburn Dance Academy, a pre-professional training institute housed within the Los Angeles-based Colburn School. Launched by L.A. Dance Project founder and Paris Opera Ballet Artistic Director Benjamin Millepied, the academy serves a small group of young men and women between the ages of 14 and 19, providing individualized instruction and mentorship from an all-star roster of permanent faculty and guest teachers. In addition to ballet, the aspiring artists study drama, music and other movement forms, and enjoy regular cultural outings in Los Angeles.

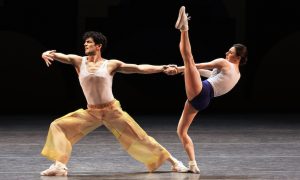

Jenifer Ringer and James Fayette performing in George Balanchine’s ‘Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet’. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

At the helm of the program are Ringer and her husband, Associate Director James Fayette, for whom the opportunity to relocate their family across the country and embark on a fresh phase of their lives could not have come at a better time.

“When I started contemplating retirement, James and I knew that we would need to move out of Manhattan, both for a change and for financial reasons,” she said. “Benjamin Millepied called me to say that he had a project he thought I would be perfect for and he connected me with the president of the Colburn School, who had a strong desire to establish a great ballet program. James and I felt like it was the perfect time for us to have a bit of an adventure, so we did it.”

And an adventure it has been, personally and professionally, as Ringer and Fayette have juggled settling into their new positions (Fayette has also taken on the title of managing director for L.A. Dance Project) with building a solid home for their two young children (the four just moved into their first house). These roles seem to be very much intertwined for Ringer, who firmly believes that creating a supportive, stable, almost familial learning environment is of equal importance to providing a rigorous training regimen and a first-hand taste of company life.

“Because the program is very small, we’re able to really focus on the students individually,” she explained. “It’s a big responsibility and an honor to have them looking to us for both technical and emotional guidance . . . and we try to treat them as complete humans. We want them to feel self-confident and individual, to know that they have a voice and a value so that when they go out into the world as adults, no matter what they do, they’re prepared.”

Colburn Dance Academy Audition. Photo by Benjamin Millepied.

This holistic approach to education springs from Ringer’s own experiences as a student, particularly in the classroom of her long-time mentor, Nancy Bielski. “Nancy doesn’t play any games,” Ringer asserted during our interview. “She gives a hard class, but makes sure you’re ready for it. She also cares deeply about her students and tries to make personal connections with them.”

Case in point: During the darkest hours of Ringer’s performing career, when living the dream had segued into an all-encompassing nightmare, it was Bielski who sparked her return to the studio. In a passage from her memoir, Ringer recalls Bielski offering a gently convincing invitation to “come back just for you. Not to dance professionally or anything. I think it would be good for you to just move to the music. I don’t care how you dance or what you look like . . . Just come back.”

More than a decade has passed since that pivotal encounter. In that time, Ringer has completely redefined the comeback, revealing herself to be not only an unforgettable performer, but also a compassionate teacher, an energetic director, a devoted wife and mother, an expressive writer, and an inspiration to friends and fans in the ballet world and beyond. Above all, she has achieved that elusive sense of humanness she once felt to have lost. She has learned to be herself.

By Leah Gerstenlauer of Dance Informa.

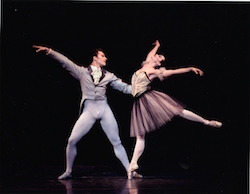

Photo (top): Jenifer Ringer’s farewell performance bows with the New York City Ballet in Union Jack, choreographed by George Balanchine. © The George Balanchine Trust. Photo by Paul Kolnik.