New York Live Arts.

June 24, 2015.

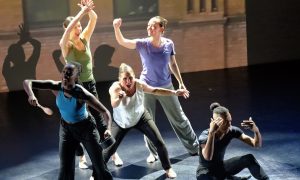

ZviDance, directed by Zvi Gotheiner, recently presented the world premiere of its newest work Escher/Bacon/Rothko, an evening-length piece in three parts inspired by the paintings of M.C. Escher (1898 – 1972), Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) and Mark Rothko (1903 – 1970).

Gotheiner’s choreography was partnered with original music by Scott Killian. In a note from Gotheiner that accompanied the program, he explained that these three modern artists had a large impact on him when he worked as a visual artist. Escher’s work is described as mathematical, playing with patterns, perception and space. Bacon’s work is described as bold, emotionally charged and raw. Rothko’s as luminous, glowing and engulfing.

The first section, Escher, premiered under a different name in 2012. In its present form, the presentation of the dancers largely alternated between group sections and duets. The first notable moment came with a duet that began with dancer David Norsworthy sitting downstage center. His spazzy little solo with intricate movements was quite different from the movement preceding it and would turn out to be completely different from anything in the rest of the show. While Norsworthy’s body chirped, his partner Kuan Hui Chew approached oh so slowly, eventually reaching him, leading to a duet with spunk and personality. Sadly, that was also something quite different from much of the show. To reveal personality was a great treat to see in the moment. The piece continued with some nice woven group work, somehow not quite mesmerizing in its repetition and flow but an effective cannon, and three more duets that had a range of energies. The duets were the heart of this section.

The first section, of course, was the audience’s introduction to most of the dancers. I had not previously seen ZviDance, so this was my first look at the current company. I found most of the dancers to lack articulation, particularly in the spine and the feet. While I do appreciate a pointed foot, I do not find it necessary. I do, however, expect that a dancer will use his or her feet to decelerate their movement, one of the things that makes jump landings quiet and makes dancers and their incredible physical control so phenomenal. Their minimal range of spine movement was the most bizarre thing to see in a piece like Escher, where the choreography included a surprising number of body rolls and snaking of the spine.

ZviDance presents ‘Escher/Bacon/Rothko’. Photo by Heidi Gutman.

By the end of Escher, I really needed the compulsion of Bacon. The four male dancers entered wearing button-down long-sleeved shirts, ties and slacks, and began to make wildly exaggerated gestures with their mouths, as if they were dressing or undressing themselves with their mouths. They broke into strong rhythmic patterns enhanced by the music (the first instance of this thus far in the evening and quite effective) and then returned to their line-up of mouthing gestures. By the end of this, one man, Alex Biegelson, had gotten rid of his pants, and began a threatening walk as if daring the viewer to engage with him. It hinted that he was transitioning his manliness into something not quite as contained and easily constrained by a tie or a dress shirt and it’s sociocultural associations. The three others lost their pants and gave the audience their own stare-downs. Chairs came out and three men sat while Derek Ege effectively continued the transition into a more primitive and ruthless man, regressing to the unrefined exhibition of power of the ape rather than the executive. A third solo by Northworthy leads into an animalistic, yet modern, display of power, the wrestling match, a ring momentarily defined by neck ties. Biegelson and Norsworthy go through several literal rounds of slow-motion stylized wrestling take-downs, a bit too literal but still very well executed by the dancers, until the fourth and last where Biegelson thrusts his hands through the costume’s chest of Norsworthy, leading to his dramatic death and a final tap out. The whole section, which had great lighting by Mark London, effectively showed the transition of the demonstration of power from idle threats of the business class, to posturing like primates, to physical violence, to killing.

At this point, Norsworthy and Ege in particular have set themselves apart with their visually satisfying movement quality.

The final section, Rothko, was notable for the music, lighting and costumes all working well as individual entities as well as in concert with each other. The dancers were dressed in a glowing blue and spent a lot of time with their backs more or less to the audience, which wasn’t particularly appealing. The movement was enjoyable though, once again primarily moving between group work and duets, the latter of which were surprisingly similar to those in Escher. Of note, Chelsea Ainsworth flew through the air in a solo taking her to every corner of the stage, where she dove to the floor and rolled with her legs suspended just so. Towards the end of the section’s journey, a duet with Biegelson and Samantha Harvey offered one of the evening’s few forays into emotional connectivity between the dancers on stage. Harvey made the most effort to make it as if she were actually dancing with Biegelson, and not just near him or resulting from him. It would have made the whole performance infinitely more satisfying if that had occurred throughout the show and among the whole cast.

By Leigh Schanfein of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): ZviDance presents Escher/Bacon/Rothko. Photo by Heidi Gutman.