New York City Center, New York.

December 9, 2015.

One expects to see a combination of physicality, grace and expressiveness when at a performance of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. One would also hope to experience inspiring choreography and emotive music. This time around, at Ailey’s 2015 City Center Season in NYC, running December 2-January 3, Ailey delivered, for the most part.

The program on Wednesday, December 9, was highly anticipated, with Dutch choreographer Hans van Manen’s Polish Pieces; the world premiere of Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America: First Movement; the company premiere of No Longer Silent, choreographed by Ailey Artistic Director Robert Battle; and Rennie Harris’ Exodus, also a world premiere.

The company no doubt looked as strong, connected and passionate as ever, and although the program started with choreography that felt a little less inspiring, we left the gorgeous City Center theater with stunning images of the company and the stories it has to tell.

Ailey dancers Jacqueline Green and Yannick Lebrun in Hans van Manen’s ‘Polish Pieces’ at the Paris Theatre du Chatelet. Photo by Pierre Wachholder.

In van Manen’s Polish Pieces, the dancers were clad in bright-colored unitards (a costume perhaps only this company can pull off so well) with flesh-colored ballet slippers, and were driven by the music of contemporary composer Henryk Mikolaj Górecki. The piece is slightly Cunningham in style, with angular and geometric shapes and traveling patterns. It’s a strong ensemble work, in which the company proved they had been well-rehearsed. The dancers’ movements were often sharp, staccato, with a focus on their hands and arms – either waving in the air from right to left or pressed against their thighs. These motions continued throughout the piece, recurring in different stage patterns. Polish Pieces is certainly a very visual and abstract piece, but I almost wished it had gone a bit deeper.

The redeeming central duets, however, were danced beautifully by long-time Ailey members Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims, and then Akua Noni Parker and Jamar Roberts. The first duet exuded such sensuality, and the second showcased a lovely sense of balletic lyricism that was refreshing after the complex, abstract ensemble work, which becomes the “chorus line” for these central characters.

Abraham’s Untitled America: First Movement is the first of three sections that the choreographer will develop next year. This section, only lasting a few minutes, featured the trio Ghrai DeVore, Chalvar Monteiro and Jamar Roberts, dancing to a score of Laura Mvula’s “Father, Father.” Abraham, a 2013 recipient of the MacArthur “Genius” fellowship, certainly does have an original style – fusing elements of hip-hop, pop-and-locking, athleticism and lyrical contemporary dance. And the movement is suited well for the virtuosic Ailey dancers.

The dancers begin to tell a story – there is a father figure, and he, eventually followed by the remaining two characters, leaves, dispersing through a long white strip of light into the dark unknown.

Program notes relate that this piece is Abraham’s exploration of the impact of incarceration in the prison system on individuals and families across generations. In only a few minutes, the dancers do evoke such sorrow, darkness and grief, and we wonder where these characters have disappeared to, or how and if they’ll meet again.

Ailey’s Jacqueline Green in Kyle Abraham’s ‘Untitled America: First Movement.’ Photo by Paul Kolnik.

It’s hard to judge this piece on only one very short section, but I hope that DeVore gets more opportunity to shine in the later sections.

Many Ailey programs conclude with Ailey’s classic Revelations, and, although at first a bit disappointed this evening didn’t include that masterpiece, the program’s second half really stepped up and proved once again that not only is Ailey a strong dancing company, but Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is also dance theater. The storytelling aspect and emotional resonance with the audience is always there.

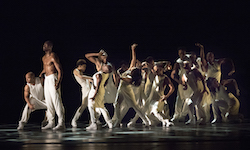

Before the curtain even opened for Battle’s No Longer Silent, we could feel the intensity. The music, by Erwin Schulhoff, played alone for several moments, setting the time period to Nazi Germany. The curtain opens, unveiling a long bench across the upstage; the dancers enter, dressed in black suits and white badge-like knee pads, shuffling on their feet or knees in military-like rows. There are groups of people – lines, clusters, circles – and as soon as the music becomes more chaotic and frantic, so do their movements. Dancers have moments to be individuals – throwing him/herself into the center, one standing tall as the others slump forward over the bench in an arabesque. But they also come back to form the collective – diagonals and circles of people with clenched fingers and wrath. It’s as if this reconnecting offers comfort; they strive to keep together as a group. Suddenly, the dancers begin to launch themselves to the floor with total abandon; the hard-hitting sounds of their bodies become almost musical.

No Longer Silent is full of many visual moments – shapes and formations are held for longer than usual – a photograph in time. The dancers bow down in a circle, as one girl is raised into the sky; a line of dancers pause, all facing and reaching toward stage right, with a beam of light projected on only their faces; various dancers backbend, almost like they’re hung from the ceiling by their belt; and one woman appears pantless among a circle of men, suggesting rape.

The lighting, by Nicole Pearce, was excellent, and helped highlight these images and offered even more dramatic effect.

No Longer Silent was highly acted and emoted by the dancers, and the intense images of the community on stage were left engrained in our mind following the performance.

Ailey dancers in Rennie Harris’ ‘Exodus.’ Photo by Paul Kolnik.

The final work on the program, Harris’ Exodus, was another deep piece and one finely danced by the Ailey dancers, led by Jeroboam Bozeman. Harris, of a hip-hop background, uses music that is part gospel, part house music and part spoken word.

The dancers first appear in a fog with pedestrian-clothed bodies scattered on the floor, with one woman crying over another’s body. Bozeman moves in slow motion toward her, and a heavenly light appears. Slowly, all of the bodies move, then start to rise and begin shaking. They break into the street dance style movement, which is made more “concert dance” by Harris’ additions of pirouettes and rivoltades.

One by one, each dancer subtly exits and returns to the stage with an all-white costume, like they’ve all made a spiritual shift, encouraged by Bozeman. He, along with dancers Renaldo Maurice and Megan Jakel, were particularly eye-catching in this piece. Harris’ effort to create a contemporary/hip-hop/dance theater work succeeded, as did the Ailey company in performing it so well.

Exodus is again about community, and the importance of the group. And, as in No Longer Silent, Exodus left the audience with haunting, powerful images, as it concludes with Bozeman, who appeared to be the initial savior of the group, beginning to descend, when Maurice steps forward to take a bullet for him.

This program was strong, particularly in the company’s ability and desire to tell stories. It showed us that they certainly have much more to say.

By Laura Di Orio of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Robert Battle’s No Longer Silent. Photo by Paul Kolnik.