Gone are the days of the traditional career trajectory for dancers: train, audition, join a company, then transition to choreography or teaching (or both) when the body gives out. More and more, dancers step into choreographer roles even while they continue to perform professionally, often supported by their companies. Troy Schumacher, a corps dancer with New York City Ballet, took that a step further in 2010 when he established his company, BalletCollective, with the mission to create new ballets through artistic collaboration.

Troy Schumacher. Photo by Henry Leutwyler.

For Schumacher, who grew up in Atlanta and trained at Atlanta Ballet, it’s all about process. He’s interested in mining ballet, which he calls a “presentational, royal art form”, for new questions and partnering with artists who inspire him to dig deeper. To foster innovation, every BalletCollective project involves three creators: a choreographer, a composer and a third artist from another genre (hence the company’s title). Schumacher choreographed all eight works in the company’s current repertory, although that’s soon to change; BalletCollective recently announced a call for choreographers for its 2017 season. Composer and music director Ellis Ludwig-Leone often creates an original score. And past third collaborators have included fashion art photographer Paul Maffi, poet Cynthia Zarin and painter David Salle.

For his next project, premiering October 27 and 28 at NYU Skirball Center, Schumacher has teamed up with architects James Ramsey and Carlos Arnaiz to create two new works. Although they work in different mediums, choreographers and architects, says Schumacher, conceptualize and discuss their work in similar terms. In its classical form, ballet values line, shape, organization and structure, while honoring it’s place in the historical canon. Architecture, which often seeks to rework old spaces using new materials and innovative design, feels like a natural partner.

Schumacher, along with BalletCollective’s creative director Luke Crisell, chose Ramsey and Arnaiz because they push boundaries and value innovation. “We look for people who really have something to say and who are doing something interesting in their field,” says Schumacher. The genre isn’t as important as the intent. “Each piece isn’t necessarily a work of the source art, but it’s a work that couldn’t exist without the source art.”

When we spoke over Skype in early August, Schumacher’s project with Ramsey was in full swing, his collaboration with Arnaiz still in the planning stages. As the creator of New York City’s Lowline and the inventor of “remote skylight”, a system that delivers sunlight underground through fiber optics, Ramsey is something of a celebrity in the architecture and design world right now. Inspired by his plans to turn an abandoned New York City trolley terminal underneath the Lower East Side into a community green space, Schumacher started with the idea of “nature reclaiming itself”.

Using Ramsey’s sketches, the choreographer worked with Ludwig-Leone to create an overall structure and original sound score for the piece. “I love the idea of taking a place that was once valuable and letting it live and thrive again,” Schumacher says. Lighting will play a major role in the final product, although as with all BalletCollective works, the ballet will exist in an empty space, abstracting Ramsey’s architectural details.

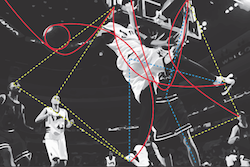

An image of Allen Iverson, depicting BalletCollective’s creative process. Photo by Carlos Arnaiz.

In his first Skype meeting with Arnaiz and composer Judd Greenstein, Schumacher wanted to let the collaboration unfold casually and without expectation. As the three artists talked about their current work and interests, the conversation moved to Arnaiz’s fascination with an essay by basketball great Allen Iverson. Iverson wrote about a player who made up in resourcefulness what he lacked in raw talent, constantly finding new ways to score goals. Coupled with a picture of Iverson mid-dunk, the essay inspired choreographer and composer to create a high energy, short and fast piece. “It going to be really physical and tiring for the dancers,” says Schumacher.

Luckily, Schumacher works with the best of the best. Ballet’s rigorous training, especially Balanchine’s neoclassical technique, “completely transforms the way you move and act”, says Schumacher. “It makes you somewhat superhuman.” And with a roster of eight current New York City Ballet dancers who work together for about six weeks a year when the company is off, BalletCollective is fueled by superhuman technique.

BalletCollective’s Harrison Coll and Ashley Laracey. Photo by Whitney Browne.

As both a choreographer and a dancer, Schumacher, who turns 30 this year, has found the roles mutually beneficial. He creates movement in rehearsal, still highly capable of translating ideas in his own body. And when BalletCollective’s season ends, he dives into City Ballet’s 22 weeks of performance with fresh eyes and a new perspective. He says, as a direct result of his choreographic experience, he’s learned to value a ballet’s overall intention over the need to “be seen” as an individual dancer. “Even when you’re in a leading role, you understand that ballets are a living breathing thing, and each person’s part serves a purpose.”

By Kathleen Wessel of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): Troy Schumacher’s BalletCollective. Photo by Marcelo Gomes.