Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, New York.

October 20, 2016.

In the theater-dance piece Letter to a Man, presented at Brooklyn Academy of Music in October, avant-garde director Robert Wilson collaborated with Mikhail Baryshnikov, one of the greatest male dancers of the second half of the 20th century. The two led us through a devastating period in the life of Vaslav Nijinsky, the greatest male dancer of the first half of that century.

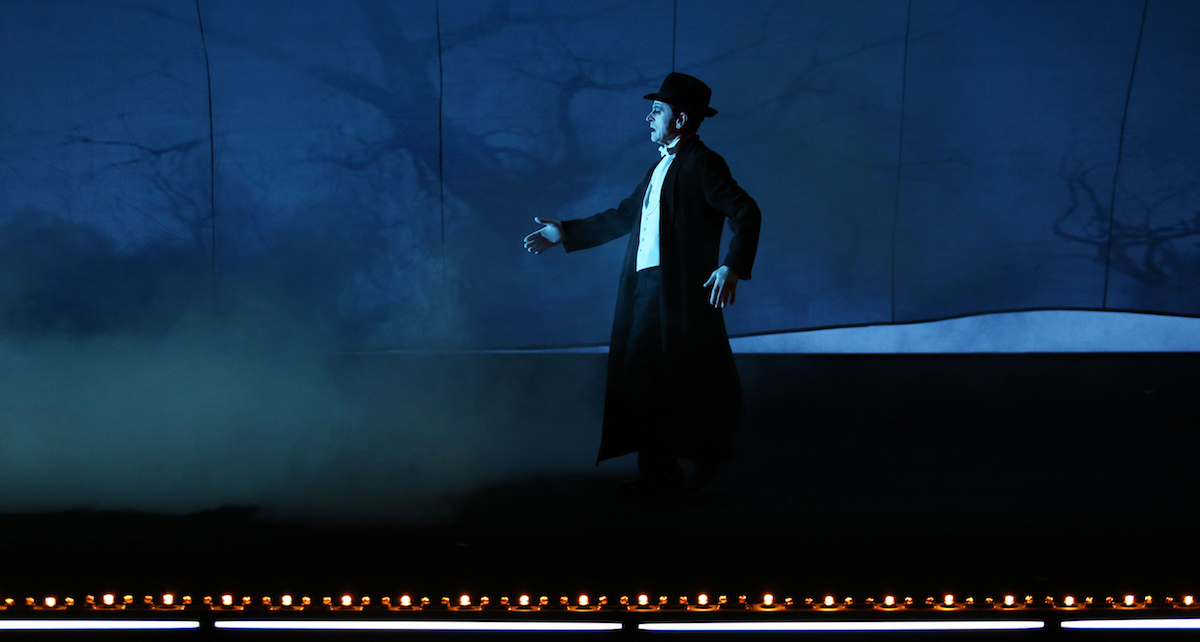

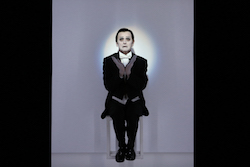

Mikhail Baryshnikov in ‘Letter to a Man’. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Projected above the proscenium during the performance were several excerpts of the diary Nijinsky wrote over six weeks in early 1919, when his wife and doctor were preparing to commit him to a sanitarium. The diary entries were powerful — searingly honest yet restrained and uninflected in a way that made them feel modern nearly a century later. The legendary dancer loomed over the Brooklyn Academy production, literally and artistically.

The entire diary is available in a version expertly translated by Kyril FitzLyon and edited by the dance critic Joan Acocella: The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky: Unexpurgated Edition (Actes Sud, 1995/University of Illinois Press, 2006). Reading it is painful and illuminating — the only time a major artist has chronicled a journey into insanity, according to Acocella. Exquisitely aware of every whisper and every maneuver being used to institutionalize him, Nijinsky wrote during a time when he knew he was losing his mind, his dancing and his freedom all at once. He was just 29.

The diary encompasses four notebooks, with descriptions of the minutiae of Nijinsky’s life — his meals, his digestion, his sleeplessness and his interactions with his wife, his daughter, other family members and servants. He ruminates at length on post-World War I politics and philosophy and the thinkers and artists of the day. He gives up eating meat. He goes to the tailor. He gives warm clothes to poor people and wants to give them more.

He tries desperately to understand and repair his relationship with his wife. “I am yours and you are mine/I love you you/I love you you/I want you you/I want you you,” he writes to Romula, then accuses her of abandoning him, of being “death” while he is “life”.

Deeply impoverished for most of his life, Nijinsky plans to make “millions” by investing in the stock market, inventing a new type of fountain pen and publishing his diary. He wants the script photographed rather than typeset, so readers feel its physicality (his “hand”). Building a bridge between Europe and America will unite the two, he claims.

His identity shape-shifts as he writes. He is Christ. He is a beast. He sees blood in the snow. He is on the edge of an abyss. God saves him. He is God.

Mikhail Baryshnikov in ‘Letter to a Man’. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

The diary includes a sometimes pleading, sometimes defiant letter to Serge Diaghilev, to which the title of the Brooklyn Academy performance refers. Once Nijinsky’s lover, the powerful Russian impresario withdrew his patronage after Nijinsky married in 1913, destroying the dancer’s career. Nijinsky writes, “I am very busy working on dances. My dances are making progress.” He calls Diaghilev “spiteful” and “a predatory beast”, then wishes he would “sleep in peace”.

Holding onto his dancing is a central concern for Nijinsky. “I am sorry for them because they think I am sick,” he writes. “I am in good health, and I do not spare my strength. I will dance more than ever …. I will not be put in a lunatic asylum because I dance very well and give money to anyone who asks me.”

The text’s seemingly simple declarative sentences deliver complex ideas as they wind from one thought to another. Nijinsky’s writing shares characteristics with his dancing, at least as far as photographs of him suggest. The camera captured angular, planar poses torqued with intricate curves and spirals. The images present him as wretched and ecstatic, bulky and evanescent, masculine and feminine, divine and animal.

A teacher once told me that training prepares one for creative work but need not determine its content. That stance perfectly describes Nijinsky’s giant leap from his classical training at the celebrated Mariinsky Ballet, in St. Petersburg — also Baryshnikov’s alma mater — to remaking ballet as its first modernist choreographer. The powerful vocabulary of Nijinsky’s schooling refined his awareness but did not dictate the parameters of his choreography.

Nijinsky made Afternoon of a Faun, Jeux and The Rite of Spring in 1912 and 1913. From this vantage point in time, we can admire the achievement — the glorious dancing, the iconoclastic choreography, even the riot that The Rite of Spring provoked in a Paris theater.

To live it was crushing. “I wanted a simple life,” Nijinsky wrote. “I loved the theater and wanted to work. I worked hard, but later I lost heart because I noticed that I was not liked. I withdrew into myself. I withdrew so deep into myself that I could not understand people. I wept and wept….”

Mikhail Baryshnikov in ‘Letter to a Man’. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Back to Brooklyn: The Wilson production captured little of Nijinsky’s frantic vulnerability as he succumbed to what was probably schizophrenia. Baryshnikov’s vaudevillian movement forays were aggressively assured. Wearing a tuxedo or dark suit and whiteface makeup that was somewhere on the spectrum from Petrushka to Cabaret, he manipulated a chair and geometric set pieces that evoked Nijinsky’s final performance in January 1919. The mood was sometimes poignant, as when Baryshnikov stood facing the projection of a prison-like window on a gray wall; overall, though, the action was clever and sexy.

Jarring theatrical contrasts offered a clichéd snapshot of madness. The lighting snapped from brilliant green to lavender to bright white to shadows and back again, while the soundtrack offered a succession of jazz, Tom Waits, Henry Mancini, gospel songs, machine-gun fire and much more. Yet, the show’s high energy and flashing lights did not save it from being surprisingly boring, or perhaps made it so. The performance closed with Baryshnikov purring a drawn-out “Nijinsky”, before disappearing through red curtains placed upstage to form a proscenium within the proscenium.

Nijinsky ended his diary and public life with letters “To Mankind” and “To Jesus”. His final words declare: “je suis je suis.” In English: “I am I am.” His presence in Letter to a Man wiped the stage of all else.

By Stephanie Woodard of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): Mikhail Baryshnikov in ‘Letter to a Man’. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.