It is the brutal irony of dance that with years of experience comes both wisdom and degeneration of the body. Older dancers often mourn their loss of balance, flexibility, agility and strength while younger dancers try to ignore the inevitable. Martha Graham, famous for her flair for the dramatic, once said a dancer “dies two deaths: the first, the physical when the powerfully trained body will no longer respond as you wish.” But the second part of that quote often goes unnoticed. She continued, “I never choreographed what I could not do,” meaning she altered steps in her work to accommodate the change in her body. Although youthful athleticism is fun to watch, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Performance maturity and nuanced movement qualities can take years to develop.

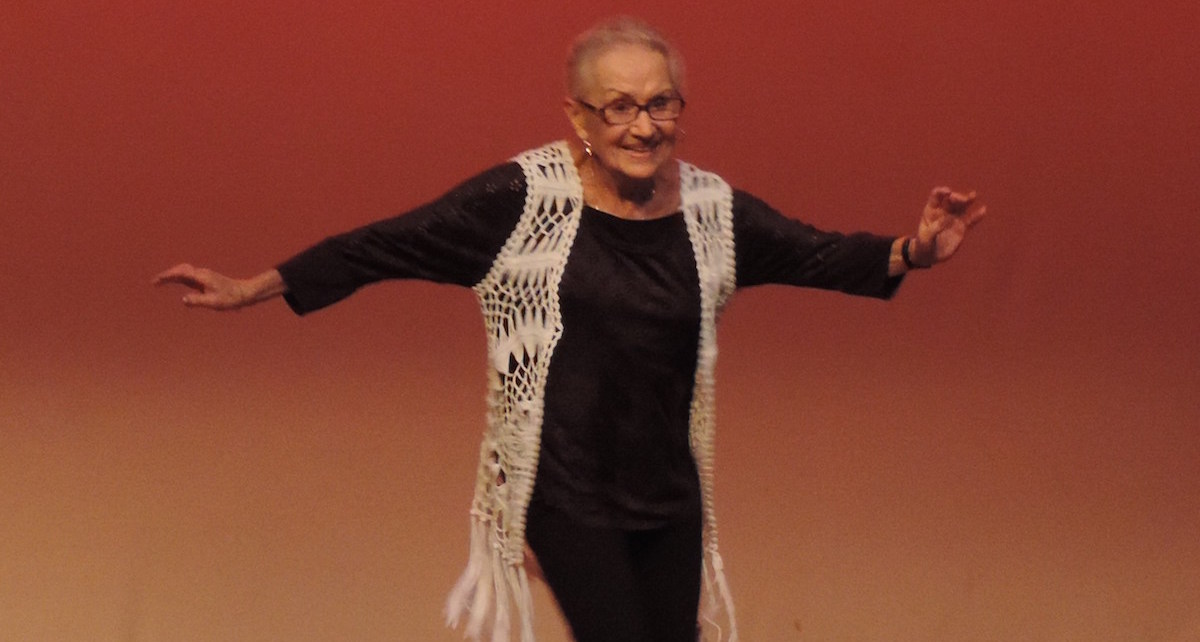

At the age of 90, dancer, teacher and choreographer Maxine Ross embodies that spirit of growth, gracefully embracing change rather than fighting it. Regal and stylish, wearing black-rimmed glasses with her silver hair pulled back, we chat over Skype from her hometown of Toronto. She tosses out a barrage of stories – of two former dance partners and countless students, of tours with the Canadian army to Japan and Korea during the Korean War, of pioneering dance on television (we’ll come back to this later), of her time in New York City and a world tour with the Dorsey Brothers – all of them punctuated and crystallized in her vivid memory.

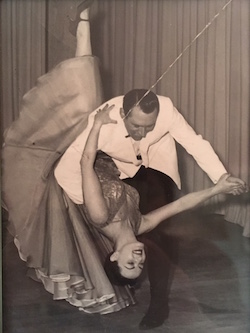

Maxine Ross and Dennis Moore. Photo courtesy of Randy Klaassen.

At 16, Ross joined forces with Dennis Moore, her first partner, and the duo was dubbed simply “Dennis and Maxine”. As part of a televised variety show, they performed a 25-minute act that included five dances from “the sublime to the ridiculous”. Their act began with a balletic waltz, then went into a tango and a comedic parody of the famed dancing couple Vernon and Irene Castle. Later, Moore performed a tap number as Ross changed into her costume for the flapper dance finale. Audiences loved it. Ross says performing in those early days of television was especially difficult because of the limited amount of space the camera could cover. They had to rehearse on a strip of white tape, practicing lifts inside a small square to keep them in the shot.

I later discover that Maxine Ross is a stage name. For her 90th birthday in October of last year, Ross’s friend and author Randy Klaassen published her memoirs in a book titled Maxine Ross: Memories of a Dancer (available on Amazon at here). In it, Klaassen introduces seven-year-old Kay Steinberg, who started dancing in 1933, the year after Adolf Hilter was elected Chancellor of Germany. The daughter of Jewish Russian immigrants, Steinberg experienced anti-Semitism at a young age and changed her last name to avoid discrimination. Perhaps a nod to the role dance and performance continue to play in her life, she signed her emails to me “Maxine/Kay”.

After a fulfilling dance career, Ross and her husband built a studio in their basement where she started Maxine’s School of Dance. Successful on the competition circuit, the studio’s reputation grew, and soon Ross had to move her dancers out, renting space in multiple locations to accommodate the numbers.

Eventually, the pace caught up with her and she closed her studio, but Ross still teaches tap classes once a week at the Maple Academy of Dance in Toronto. Her students are a devoted group of adults, many of whom took her classes as children and returned – sometimes decades later – when they heard she was teaching again. Ross calls herself their “second mother”; she leaves time during every class to discuss their lives and brags about their accomplishments as if they were her own children. (She also has two sons, seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren).

Inspired by Ross’s teaching, former student Kim Chalovich left her engineering career to open the Tap Dance Centre in Mississauga, Ontario, the first studio in Canada devoted entirely to tap dancing. For Ross’s 90th birthday, Chalovich asked her former teacher to perform a tap duet. “She asked me to do most of the choreography,” says Ross, “probably because she thought I’d have a senior moment. But I don’t have senior moments. Not yet!”

Although she’s been dancing for over eight decades, Ross is far from old-fashioned. In order to stay motivated and fresh, she advises all dancers and dance teachers: “Never stop taking classes.” While living in New York City, Ross took a class taught by the legendary Katherine Dunham and later incorporated Dunham’s isolations into her jazz classes. An insatiable appetite for learning “gave me the incentive to keep going on because I wanted to do better.” Even into her 80s, when she began to feel embarrassed about her age, Ross kept going to classes. She watched and took notes, then arranged private lessons for herself. “I needed to be invigorated and to keep up with the times,” she says. “You have to keep your mind rolling.”

Despite her open mind and evolving tastes, nostalgia creeps in when Ross talks about ways in which dance has changed over the years. She’s quick to acknowledge the substantial improvement in training. Dancers today are beautiful technicians, she says, with higher legs, stronger bodies and quicker feet than ever. But she misses the balletic flow, the joy and ease of a past generation not so focused on impressive tricks. When Ross watches Dancing with the Stars today, she says, “It’s all so sharp and hard, and I think, ‘My god, slow down. Just relax and enjoy it a little bit.’” As a dancer, teacher, choreographer and fellow human myself, I think I’ll take this advice to heart. Maxine Ross has years of experience and a body of knowledge to show for it.

By Kathleen Wessel of Dance Informa.