They say that costuming can make or break a performance. If your dancers are stellar, it won’t matter, bad costumes are merely a dent in a solid structure. But also, if your dancers are stellar, beautiful costuming can push the production over the top. Fortunately, for Richmond Ballet, strong dancing and engaging dancers were fully supported by solid, rich, intelligent costuming throughout the repertory for their recent run at the Joyce Theater.

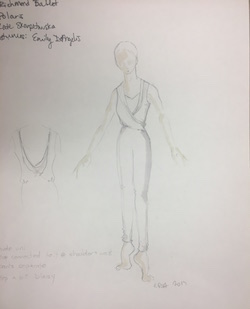

Women’s costume for Katarzyna Skarpetowska’s ‘Polaris’. Photo courtesy of Emily Morgan DeAngelis.

Dance Informa was thrilled to sit down with the company’s Costume Director, Emily Morgan DeAngelis, to get a closer look at not just what went into the costumes but also a little bit behind-the-scenes of the costume shop culture. DeAngelis designs the costumes for new works, as well as re-designs of pre-existing pieces, and maintains the rest of the costumes for all repertory.

Because the costume shop is located in the building at Richmond Ballet, the choreographer can pop down there to see what’s being built, and DeAngelis can run up to the studios to see the choreography and if something will be problematic. They can make decisions on the fly and work really quickly. She will also bring some of the guys down to look at a costume with her, look at partnering hand positions, and see if her ideas will work. Sometimes, of course, she is not willing to kill an idea for the sake of the choreography because that element makes the piece. So they come up with some fancy problem solving, and those successful ideas often come from the dancers themselves! When choreographers come in as guests, it keeps people sharp. They have to work really quickly, make a mock-up, do a fitting and talk about finishings, and do this all in the first couple days. Then the choreographer leaves, the costume shop gets close to the finished product, and they correspond via video chat and email for final decisions. Then they tech and hope it is what they wanted!

And what if it’s not? Or what if DeAngelis doesn’t like an old set of costumes? Nobody cares because it’s not her decision. If it’s a fit issue, or it makes it hard for the dancers to do their job, if it’s distracting to dancers, they could modify the costume. Other than that, they can’t change the costumes of a pre-existing piece unless the choreographer, director and costumer all have a dialogue and collectively come to a conclusion that a change needs to be made.

But her job isn’t just sketches, trimming and sewing to a choreographer or director’s specifications; it’s also making sure these dancers feel good both inside her costumes and once they leave the shop. “It’s incumbent upon me to give them emotional concern,” DeAngelis says about the dancers, whom she considers her friends. “When they try on a costume, that’s when the role feels the most real. In a career that is fleeting and intense every day, the costume shop is a safe space.”

A costume fitting for Malcolm Burn’s ‘Pas Glazunov’. Photo courtesy of Emily Morgan DeAngelis.

When she noticed the all-too-familar way dancers have of self-deprication, especially when it came to their body, she instituted a new policy to disrupt the pattern; if they say something negative, they have to say three genuine, nice things about themselves before leaving.

DeAngelis knows how important it is for the dancers to feel great, cool, beautiful and clever in her designs, and it’s all part of a culture that supports its dancers, from the administration, to the on-site athletic trainer, to the on-site costume shop. She explains, “If they are not healthy, none of this works. The dancers should be happy and healthy, and I am a part of that [mentality]. It wouldn’t work if there weren’t a community relationship in the company, for audiences and everyone who works in the building.”

Here is what DeAngelis and Richmond Ballet brought to the Joyce:

Swipe (2011) was choreographed by Val Caniparoli, with original costumes by Sandra Woodall. The women were in blue jeggings by For All Mankind, violet leotards and flowy open tops in slinky material, the men in black slacks and dark-colored open button-down long sleeve shirts. Everything was pre-made except for the women’s tops, and, since everything already existed for this piece, DeAngelis just had to make sure everything fit the current cast.

Richmond Ballet’s Thomas Raglund in Val Caniparoli’s ‘Swipe’. Photo by Sarah Ferguson.

The choreography had lots of undulations of the upper body throughout. But there is only so much movement a loose garment will go along with, so the costumes worked best when the cast left their shirts off in the wings. Stoner Winslett, Richmond Ballet’s artistic director, is especially meticulous about pant length, and while this was brilliantly apparent for every piece in the show, it was first revealed here with the women’s jeggings rolled to individualized attractive lengths at the calf.

Pas Glazunov (1991) was choreographed by Malcolm Burn with new costumes by DeAngelis. The woman was in a simple white v-neck tank dress with a short, rippling skirt, the man in a crisp white button-down by Uniqlo and white slacks. That skirt had the perfect dish, a wide ripple with enough weight to flow but not sag. As it happens, it was just a circle skirt set a little lower at the hips, so it gently rises but is not in the way for the lifts. The dress closure was hook and bar instead of zipper because it’s easy to take it in, and DeAngelis finds this to be really important because dancers’ sizes change over the course of the week with such hard work every night. A heavy performance schedule has dancers dropping weight and expanding muscles, so the logistic of adjustments must be taken into account with the design.

DeAngelis ended up re-designing the costumes into something entirely new for these performances. Burn, the choreographer, felt that the original blue and purple costumes weren’t really what he wanted, and he insisted on white, which still gives a nod to the classical formatting of the pas. The team recognized the importance of honoring the classical format of the piece, but since it needed to fit into a contemporary program, it needed to change. “It’s like a first date” between the different pieces on the program, says DeAngelis. “You need to make a good first impression and impress each other, so we wanted it to look a little more pedestrian.”

Richmond Ballet in Katarzyna Skarpetowska’s ‘Polaris’. Photo by Sarah Ferguson.

Polaris (2015) was choreographed by Katarzyna Skarpetowska, with original costumes by DeAngelis. The women wore a soft white, flowy jumpsuit with a nearly invisible nude unitard underneath with sparkles embedded in it, the men in black slacks in multi-textured fabrics. The idea of the jumpsuits came from Skarpetowska. She envisioned a draped romper in white, which DeAngelis successfully created in a way that felt contemporary, looked flattering, and worked with the mesmerizing music, choreography and lighting. It looked street-ready.

The piece itself was created with inspiration from the cosmos, and galaxies being created. From the start, Skarpetowska, and subsequently the artistic staff, knew there would be stardust in the piece (large pieces of glitter, gently falling from the women’s hands or from the rafters), so the “goddess astronauts” (DeAngelis’ term for the women) have sparkles on their tops – as “beautiful and shimmering as your mind would think creation would look.” Hidden buttons and stirrups keep everything in place.

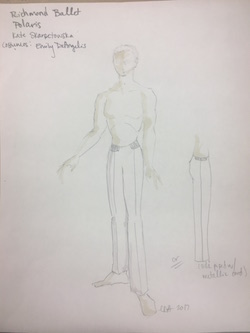

Costume design for Katarzyna Skarpetowska’s ‘Polaris’. Photo courtesy of Emily Morgan DeAngelis.

Even though they appeared to be much simpler in design, the men’s pants were also built, and oddly difficult because there is a pleat of contrasting fabric on the front and back so that when the light hits it you can see this extra dimension. DeAngelis felt it wouldn’t have been right to put the men in store-bought pants; that would have been more practical, but it wouldn’t have felt organic to the piece and its galactic origins. “The piece makes the sacred universe collide with technology,” DeAngelis describes. “We wouldn’t have the source material without NASA, but the photos and the bodies dancing feel really natural and almost mystical. I wanted to design and build pants so my dancers didn’t feel like what they were wearing was something you could just find walking down the street because there is nothing pedestrian about the movement or intent of the piece.”

Lift the Fallen (2014) was choreographed by Ma Cong, with original costumes by Rebecca Baygents Turk. The women wore faux corset tops with a lacy pattern and chiffon skirts with both a short and a long removable layer; the men wore corset-like tops that were complimentary to those worn by the women, along with dance tights. All of the costuming faded from a bright, warm yellow at the bottom to white on top. The piece is a tribute to the choreographer’s mother, who had passed away not long before he created it for the company.

Richmond Ballet in Ma Cong’s ‘Lift The Fallen’. Photo by Sarah Ferguson.

Cong found that creating the work was a form of therapy, and he tried to explore where and in what direction it could help with the deep emotions he was feeling since his mother passed. It allowed him to focus on something positive, beautiful and spiritual, and also led him to consider what his mother liked and what she would have liked to see. Something that came to the forefront was the yellow rose, his mother’s favorite flower, which, along with the positivity of the color, is why the costumes have the lovely yellow hue. His other wishes expressed to Turk were something very elegant, with a little touch of contemporary, that would show the true side of a human being.

They decided that because the music has a dramatic up and down to it, like a wave, the costume should have a flow – hence the long skirt. But in the rehearsal process, he liked the way the women looked in their shorter rehearsal skirts, so they came up with the idea that there would be two overlaid skirts, a long and a short, and the long could be removed for certain sections of the piece. Chiffon would be the perfect material to give a gorgeous flow and to not add excess bulk in the layers. The corset look added a Victorian feel. “Rebecca did really fabulous work combining all the elements,” says Cong.

Richmond Ballet in Ma Cong’s ‘Lift The Fallen’. Photo by Sarah Ferguson.

The costumes look achingly beautiful on stage, and that is not just design but also extensive care. The costumes need to be rebuilt after frequent and strenuous use. “The piece is so beautiful, a signature piece for the company at this point,” says DeAngelis. “We know we are going to do it over and over again, and we want it to look as beautiful the 50th time we do it as it was the first time.”

By Leigh Schanfein of Dance Informa.