The Nutcracker – a beloved holiday classic that graces stages across the nation, and across the world. Come December, Tchaikovsky’s iconic scores fill spaces from department stores to supermarkets (and grate the ears of dancers who’ve heard them countless times in rehearsal and performance).

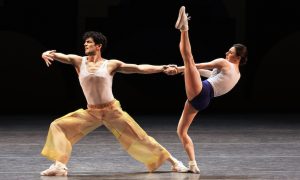

Boston Ballet in ‘Mikko Nissinen’s The Nutcracker’. Photo by Liza Voll, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

By and large, most Nutcracker productions offer period dress, the conventional set of characters with their typical inter-relationships, and the same (or quite similar) “Land of Sweets” variations. It’s what most audiences have come to expect, and what they know they’ll enjoy, and dance companies can count for revenue and audience engagement. Most often, all seems well in Nutcracker land.

Yet recent cultural discourse has raised questions about how much this classical take reflects our modern values, such as inclusivity and equality (in regards to race, gender and cultural background). The New Republic flat-out called it “racist”. Dance Magazine also addressed the matter but took a more objective tone, interviewing three company directors with viewpoints spanning the spectrum of opinion on the topic.

There’s also simply the question of if change could be due when art lasts so long. The world changes, and so do artists and audiences. The counterpoint to that is how some art is timeless, and we shouldn’t let it fade – and thus lose what it has to continue offering to us – just because the world changes. All of this considered, many Nutcracker productions have stepped away from a hundred-plus-year-old tradition and into a more modernized take – at this point even making the pages of dance history, such as with Mark Morris’ The Hard Nut.

Boston Ballet Artistic Director Mikko Nissinen. Photo by Liza Voll, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

Dance Informa also spoke with three choreographers to get their views on the need for change, or lack thereof, and how that manifests in their Nutcracker productions. Mikko Nissinen, artistic director of Boston Ballet and choreographer of Mikko Nissinen’s The Nutcracker, turns the cultural and racial discussion toward diversity.

He shares Boston Ballet’s clear efforts toward casting all kinds of dancers in all kinds of roles, in order to have performances – and the company at large – “reflect the community where we live,” he shares. Nissinen adds that diversity goes far beyond skin color. In addition, cultural respect lies in offering portrayals of those from another culture with style and grace, rather than as parodies, he asserts. Some of this is in aspects as straightforward as not “overdoing” makeup and costuming.

“In the world of art, like in cooking, you have ingredients, and you do what you do with them,” Nissinen says.

CONNetic Dance’s ‘Nutcracker Suite & Spicy’ Photo by Bill Morgan.

There’s enormous possibility for what choreographers can create within the tradition of any one show. Carolyn Paine, artistic director of CONNetic Dance (Hartford, CT) and choreographer of the company’s annual Nutcracker Suite & Spicy, evidently embraces that openness. The company’s Nutcracker includes many modern aesthetic elements, as well as many different dance forms. Toward the diversity and cultural sensitivity question, Paine calls upon the vast amount of talent from a wide range of cultural, racial and stylistic backgrounds within greater Hartford.

Lynn Parkerson, artistic director of Brooklyn Ballet and choreographer of the company’s annual The Brooklyn Nutcracker, sees authenticity as a key to cultural respect. She has some “Land of Sweets” variations featuring masters in the dance forms of the culture front-and-center in the variation in question – such as a belly dancer in the Arabian variation. Paine’s production takes a similar strategy, such as the Spanish variation as a Latin ballroom dance.

Brooklyn Ballet’s ‘The Brooklyn Nutcracker’. Photo by Lucas Chilczuk.

It seems as if this is a simple way to honor the cultures exhibited in this section of the show, while avoiding any kind of mockery or cultural appropriation – all while broadening audience members’ knowledge of the dance that’s out there. A counter-argument to that might be that maintaining these variations is part of maintaining the treasured tradition of the show overall. As Parkerson points out, however, “Someone will always do the classical, traditional version. The New York City Ballet Balanchine Nutcracker isn’t going anywhere.”

Paine believes, with legitimacy, that both classical and modernized takes on the holiday classic can do well. Modernized takes can become a “new” tradition for some individuals and families, she’s found. Some in her annual Nutcracker audience come to expect such elements as modern covers of Tchaikovsky scores, the inclusion of hip hop dance and more modern dress in costumes.

Carolyn Paine. Photo by Kevin Soucie.

The mouse in her production is a “club rat” (her second act of the production set in a nightclub, in a family-friendly way), somewhat shady characters invading Clara’s space. The “soldier” characters help her stave them off, but ultimately she is the strong one to defeat his advances and say no. It’s an arguably more realistic and satisfying take on these characters and the scene. At the same time, it honors the classical convention of Clara finally defeating the Rat King by throwing her shoe at him – while taking it further, to give Clara more agency and strength.

Paine’s Clara is also a young woman, versus the child of traditional productions. (In fact, there are only three younger dancers in the show overall.) This seems to be a simple fix for anyone feeling disturbed that Clara is a child while the Nutcracker Prince is far older. Nissinen doesn’t give credence to the view that there’s anything disturbing in that classical arrangement of characters, that any thoughts of the sort are in audience members’ minds. “It’s from Clara’s perspective,” he explains, and not indicative of anything coercive on the part of the Nutcracker Prince.

Boston Ballet in ‘Mikko Nissinen’s The Nutcracker’. Photo by Liza Voll, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

In this take of the story as a window into Clara’s mind, Nissinen says that he seeks “to complete the story” in his Nutcracker productions, which not all takes do, he feels. Parkerson has other ideas for the storyline, which she’d like to some day develop – such as more of a sibling take, with Fritz coming along with his sister Clara to the Land of the Sweets, as well as a perspective of Drosselmeyer looking back on his childhood. Such thinking demonstrates how many different ways we can present the story, how much creativity we can have.

There can be an understandable fear among company administrators that with veering away from tradition, a reliable audience base might be lost. Yet, as Paine asserts, when it comes to The Nutcracker, the old saying rings true: If you build it, they will come. There’s also a perception out there that The Nutcracker is the financial lifeblood of many ballet companies, allowing the funds to do more experimental and contemporary work at other times of the year.

Brooklyn Ballet’s ‘The Brooklyn Nutcracker’. Photo by Lucas Chilczuk.

Nissinen, at the artistic helm of the renowned and reputable Boston Ballet, affirms, “The Nutcracker helps dance companies, but it doesn’t help them exist.” Reliable donors, grants, endowments and other such funding sources are rather what provide many dance companies’ financial stability. Those sources will most likely not disappear with experimentation and risk-taking around the classics, The Nutcracker included. In fact, donors might appreciate the “stepping outside the box”, and grant applications might have a stronger case.

We could shift that old saying a bit, and it still holds true – continue to build it (even of in different ways), and they will continue to come. “When it comes to the holidays, people want tradition,” Paine asserts. “You can give them a new tradition.”

Classical tradition can be a beautiful thing. So can adjusting the tradition to be more in accord with a changed, and rapidly changing, world. With all of The Nutcracker productions out there, we can have both. Individual dancers and choreographers must find what is most true to their vision and highest values. Either way, The Nutcracker can be a unifying, joyful holiday tradition for all to enjoy.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.