Paul Taylor was a true giant of American modern dance, with works that displayed both simplicity and depth of understanding into the human condition. He passed away on August 29, 2018, at 88 years of age. A spokesperson from the company said it was due to renal failure. Surviving him is a company that he founded, many admiring dance lovers and an American contemporary dance that he had a significant hand in shaping.

In a choreographic career lasting more than a half century, he created 147 works – of varying atmospheres, aesthetics and moods – for his company and others from American Ballet Theatre to Houston Ballet. From the social and human commentary he created in his works, to the lyrical quality of the movement within it, Taylor was a poet. Yet, ever practical, he once remarked that a ticking clock was his muse. Pedestrian movements were often his inspiration.

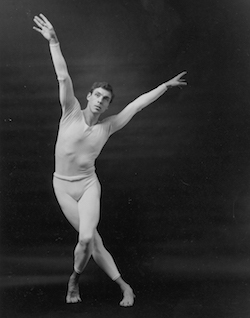

Paul Taylor in ‘Aureole’. Photo courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Foundation Archives.

Lincoln Kirstein once said that his work was set apart from all of the “idiosyncratic” modern dance he observed. Taylor’s works had the economy and wit of well-crafted short stories, along with an exquisite craftsmanship in all aesthetic aspects, explains Sarah Kaufman of the Washington Post. He was also entirely unconventional in approach, wearing flannel and jeans while prohibiting mirrors in his studios (claiming that they create “bad habits”).

Paul Belville Taylor Jr. was born outside of Pittsburgh on January 29, 1930. His mother was a businesswoman and his father a physicist, but the family’s fate changed with the coming of the Great Depression. They moved to Washington, where his father managed a hotel and his mother a restaurant. Although his mother had three children from a previous marriage, Taylor grew up “essentially as an only child,” says Kaufman. He directed his curiosity toward insects, the halls of the family’s hotel, and the various characters coming in and out of there.

Taylor attended Syracuse University on partial scholarship in the early 1950s, planning to study painting. Looking for an extracurricular endeavor, he joined the swim team. Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times describes Taylor’s interest in athletic dancers, and athleticism in dance; “many of his male dancers had powerful musculatures, while many of his female dancers displayed lissomeness, force and boldness.” Yet dance soon replaced swimming as his physical endeavor of focus.

Dancing could satisfy a need to expel his physical energy, he said in his 1987 memoir, Private Domain. He studied in Bar Harbor, Maine, in the summer of 1951, while chauffeuring for the dance school where he took classes. He was instantly hooked, Kaufman explains. The following summer, he studied at Connecticut College, with modern dance heavyweights such as Martha Graham, José Limón and Doris Humphrey. Taylor transferred to the Juilliard School in New York City, training with other notables such as ballet choreographer Antony Tudor.

Paul Taylor. Photo courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Foundation Archives.

Upon graduation, Taylor was successful as a dancer and choreographer fairly quickly. A calmly lyrical mover with both size (standing at 6’1) and athletic strength, he caught the attention of Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. From 1953-55, he was a founding member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and joined Graham’s company on 1955.

Macaulay explains how Taylor’s modernist aesthetic seemed to be most significantly influenced by Graham but with an important difference; Graham’s technique contained a “forceful expressive tension that it forged between torso and legs…[i]n her work, the body was often excitingly at war with itself[, but i]n his work, that tension would be translated into a vehemently lyrical current.”

While dancing in their companies, he created works with collaborators including composer John Cage, and designers Robert Rauschenberg and Alex Katz. George Balanchine choreographed a solo for Taylor, which he performed in New York City Ballet’s season. He left Graham’s company in 1962, in order to focus on his own company, Paul Taylor Dance Company.

His pragmatic approach remained, yet subject and style shifted over the years. Duet (1957) consisted of he and a partner in stillness for four-and-a-half minutes. Louis Horst’s witty review of the work was simply a blank page. “My movements are scribbles of what people do,” Taylor remarked in response, “and people do sometimes stand or sit still, you know.”

Yet, as Kaufman describes, he came to realize that his works needed to offer music and movement in order to be accessible to a variety of audience members – and therein keep them in their seats.

Pedestrian movement always interested him and guided his work, however, perhaps because he began dancing later in life, Kaufman believes. Taylor’s seminal work, Esplanade (1975), for instance, assembles walking, running, gliding and small, simple leaps – all set to Bach. Taylor also infused virtuosity in the work, and so many others, however; Esplanade has a richness of pattern as well as speed, in certain sections, that is itself virtuosic, for instance.

Paul Taylor at the company’s 50th anniversary. Photo by Paul B. Goode.

Due to hepatitis and ulcers, Taylor retired from the stage in 1974, at 44 years old. He remarked that it was nice “to be just be still and not hurt.” Yet he continued, and in fact deepened his work in, choreographing. Aureole (1962), set to Handel, demonstrated a joyfulness – one verging on sentimentality – uncommon in modern dance. It reflected the promise of President John F. Kennedy’s America. Further demonstrating his interest in pedestrian movement and the general quotidian, he gained inspiration for the chilling Last Look (1985) from the darting gazes of a homeless man.

For many years, the Paul Taylor Dance Company toured internationally through State Department sponsorship. The company gained international fame – exceeding that of Merce Cunningham or Martha Graham’s companies, despite how Taylor got his start from these modern dance heavyweights, says Kaufman. Taylor alumni include infamous dance names such as Twyla Tharp and Pina Bausch. Taylor founded Taylor 2 in 1994. In 2014, Taylor decided it was time for change and planning for the company surviving him. He renamed it the Paul Taylor American Modern Dance Company, and re-formatted the repertory to also include non-Taylor works from other prominent contemporary choreographers.

This past March, Taylor appointed Company Dancer Michael Novak as artistic director-designate. Taylor remained involved with the company and making work, however. With Taylor’s passing, the 35-year-old Novak will now head the school and all other entities under the company umbrella – sooner than expected, remarks Courtney Escoyne of Dance Magazine. Escoyne adds that “Mr. Taylor will be missed.”

Indeed, he will be. He once said that making dances is similar to arranging his beloved insect collections, that you shape and rearrange things until they look good – so very practical, yet so very poetic.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.