For dancers, getting injured is sadly both not at all uncommon and not at all easy. Even apart from physical discomforts and challenges, there can be much to face mentally, emotionally and spirituality. On the brighter side, what can sometimes result from that struggle is new discoveries about oneself as an artist and as a person. One can find themselves filling the void where dance once was with new self-reflection, new hobbies, new depths of connection with close friends and family, and more.

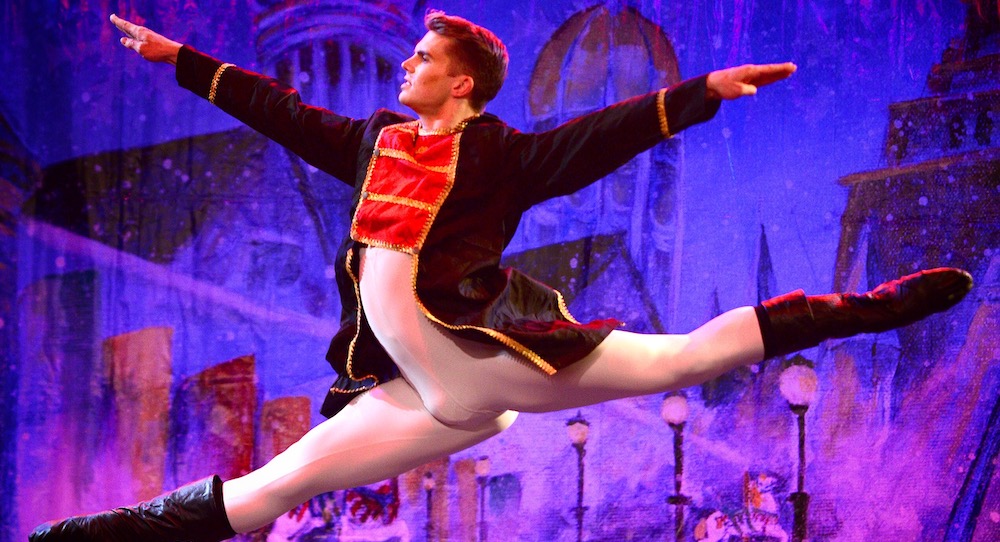

Alex Zarlengo. Photo courtesy of Zarlengo.

Alex Zarlengo, soloist at CONNetic Dance, self-described “all-around Renaissance man”, is a clear example of such a process playing out. Dance Informa spoke with Zarlengo on his injury and recovery as part of a series of dance artists’ individual stories of handling injury — the physical, mental, emotional, and more. It all started on June 28, 2017, while Zarlengo performing in The Music Man at Theatre by the Sea in Kingstown, RI. During “76 Trombones”, he heard an “audible ‘pop’ like a giant rubber band snapping,” he recounts. Zarlengo also remembers something feeling “not quite right” with his right ankle on the Saturday before that day.

He was rushed to the hospital and there diagnosed with a ruptured Achilles tendon. “It’s a rare injury overall but does happen in athletic men around my age,” he shares. The treatment ahead was multiple surgeries and 18 months of physical therapy. Fortunately, he was dancing on stage during a run of a union production, so he could get worker’s compensation over the course of his recovery (when he wasn’t performing and therefore not receiving regular paychecks from doing so).

As “Murphy’s Law” might have it, Zarlengo had also just been cast as an understudy for Gaston in the theater’s next production of The Beauty and the Beast. The mental and emotional hardships didn’t end there. For the first three months of recovery, he was on crutches. Yet “the hardest part of recovery was definitely psychological. Your greatest adversary can be yourself,” he shares. He claims that he “can’t stand not being autonomous”, so depending upon others — from receiving treatment to the most mundane of everyday tasks — wasn’t at all easy.

Alex Zarlengo.

He thinks that this “independent streak” is definitely quite common amongst dancers. For Zarlengo, as with any injured dancer who must take time away, “of course, there’s also a very conscious sense of missing dance,” he says. “We’re all so used to that endorphin high.” He asserts that being a dancer becomes an incredibly central part of one’s identity, and not dancing (even temporarily) means “deep re-learning of who you are.”

Amidst all of this, given time and space for reflection, “you really get in your own head and take a deep look at who you are,” Zarlengo adds. For instance, he had graduated magna cum laude on a Pre-Med track at Salve Regina University, and decided to step off the road toward a medical profession in order to build a performing career. With both career paths suddenly unavailable to him, his injury made very real the precarity of that new path he’d chosen. “You learn that everything in life can change within a second, and it all forces you to take stock of your adult identity,” he says.

One might think someone in this situation would dive deeper into social media friend groups, but Zarlengo actually took time away from it. He shares that he did have a great support system of family and friends. His roommate, Carolyn Paine, experienced injury around the same time, and they could be strong supports for each other, he shares. With newly open time and space, Zarlengo also began to sew costumes, therein building a new creative skill and passion. In a situation like the one he experienced, “you discover new interests, and that you can do other things [besides dance],” he explains.

Alex Zarlengo. Photo courtesy of Zarlengo.

This past January 11, Zarlengo’s surgeon cleared him to dance again. He had danced the role of the Nutcracker Prince in CONNetic Dance’s The Nutcracker Suite and Spicy the month before, however. He shares how his first time back in class was with Sheila Barker at Broadway Dance Center in late January. “I cried during the warm-up because I was so grateful to be there, and afterward she approached me to tell me that I looked great and that I had improved. She had no idea that I had sustained an injury on that scale, and I was flattered because she assumed I was out on tour,” he recounts.

Zarlengo still does have some unsteadiness in his right ankle on relevés due to muscular atrophy. Yet, overall, he says that his technique has actually improved from doing such extensive physical therapy. “I’m still somewhat modifying things, if not just being more careful,” he explains. He encourages mindfulness in fellow dancers, to listen to their body and know their limits. He also urges gratitude and healthy perspective, and adds, “Be grateful for any time you can step on that stage. Remember that there are people who can’t be there.”

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.