How much do dancemakers create for themselves, and how much do they create for those who view their works? It’s a perennial tension in dancemaking — particularly in contemporary dance, wherein shifting values and mores allows for shifting the relationships artists have with audience as well as traditional authority structures. How much of the work is about the inner, and how much is about the outer? There’s a balance there that Mark DeGarmo — founder, executive and artistic director of Mark DeGarmo Dance, as well as dance educator, dancer and researcher — seems to have found.

Mark DeGarmo. Photo by Leon Anthony James.

Dance Informa speaks with DeGarmo about his journey in dancemaking, his company’s work in performance in community outreach, the place of the political in his work and more. He shares that he’s always been interested in the written word, theatricality and the arts overall. He found his way to dance as a 15-year-old, despite stigma about young men dancing. He immediately wanted to choreograph. DeGarmo attended The Juilliard School, and graduated in 1982. He founded Mark DeGarmo Dance that same year. Five years later, in 1987, the company obtained non-profit status.

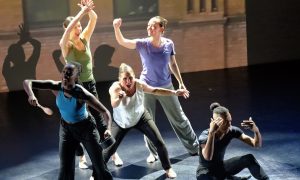

Thirty-two years later, the company is still going strong. DeGarmo currently has many works in repertory or in process. A favorite is a work on Frida Kahlo as well as an ode to Mexico, Las Fridas. DeGarmo describes it as a “transmodal/performance art that draws upon many modalities”. He describes striking evidence that the work really landed with audience members. “They were visibly shaking and saying things to me like, ‘I have to go home and do (x) and (y) thing. There’s only today!’” he recounts.

DeGarmo asserts that this ability for his work to “reach across the footlights”, to really resonate with viewers, is key to him through his creative process and in how he evaluates his work after the fact. This dynamic was recently front-and-center in regards to editing his autobiography, which he’s currently in the process of writing, he explains. He notably re-worked a large section he’d be reading aloud once it really hit him that there’d be an audience listening.

Mark DeGarmo and Marie-Baker Lee in ‘Las Fridas’. Photo by Leon Anthony James.

DeGarmo truly walks this walk, as well as talks this talk, about recognizing audience experience of the work. The company offers “salons”, in which members of the general public can come view works-in-process and offer their views. He attests that audience feedback at these salons was particularly influential in the creation of Las Fridas. He’s also sure to credit iconic choreographer Liz Lerman with the main audience response frame that these salons call upon, called Critical Response Process. “We get siloed into our fields, and helpful to hear from lots of different people with many different backgrounds, and through that broaden our influences,” he asserts.

An untitled and forthcoming evening-length work, a group of three different solos, is undergoing this salon process. One solo portrays Raymond Duncan, Isadora Duncan’s brother who was a visual artist in his own right. The work draws upon clowning, in which DeGarmo is also trained. Another solo in the work is on the infamous Transcendentalist writer, philosopher and naturalist, Walt Whitman. A third solo, “The Metrics of Awakening”, is more of a “technical study,” DeGarmo explains. The impetus for this work of three solos came from two main sources, he shares.

One, he felt a draw to perform more frequently again. Two, he obtained a secondary studio space, offering a creative oasis away from space used for administrative work — and, with this new space, he felt even more drawn to create work for himself to perform. He shares how it’s not all that common for an older man to dance on stage, and how defying cultural expectations in this way is even a “political act”.

Mark DeGarmo. Photo by Reiko Yanagi.

After saying this, DeGarmo chuckles and shares a favorite quote from a personal influence of his, choreographer Hanya Holm: “You can use age as an excuse if you want to.” Other influences include Buffy Sainte-Marie and Carmen de Lavallade. All in all, personal experience met outer conditions to lead him to create this work of solos, leading to further meaningful experience for both himself and viewers.

Also in an effort to engage broader communities in dance and challenge narratives around the art form, the non-profit Mark DeGarmo Dance brings dance education and art-making experiences into New York City public schools. The organization’s website shares research finding impressive empirical evidence that dance spurs important developmental gains — physical, social-emotional, educational and more. DeGarmo shares a powerful memory of students tasked with making work on a meaningful social issue, and they created works on issues ranging from gun violence to the “#metoo” movement to environmental concerns. They performed for students younger than them, who were fully transfixed, DeGarmo recounts.

Mark DeGarmo and Marie-Baker Lee in ‘Las Fridas’. Photo by Leon Anthony James.

He acknowledges difficulties with arts education receiving the legitimacy, funding and other needed forms of support it deserves. He advocates for being vocal about why it really matters and recounts a personal anecdote illustrating how that can indeed be effective; he and five colleagues speaking up about the lack of recognition of the arts in an official political speech seemed to result in the arts being mentioned in a later speech.

That was a personal experience with impact far beyond him. This thread of the inner and outer seems to be one through the work and operations of Mark DeGarmo Dance. Perhaps that’s a thread for an artistic tapestry that’s more widely viable, meaningful and widely impactful.

For more information on Mark DeGarmo Dance, visit www.markdegarmodance.org.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.