Some stories — and thus, some dances — are simply timeless. At the same time, there may very well be creative choices within works from the past — even if they feel timeless — that don’t align with values of the present. This tension was at play in the recent restaging of José Limón’s The Traitor at the University of Florida (UF). The 20-minute work tells the biblical story of Judas Iscariot handing over Jesus of Nazareth to Roman authorities, leading to his crucifixion.

For the past 60-plus years, this work has been performed by an all-male cast, yet this restaging was performed by men and women. In fact, the two main characters — Judas and Jesus — were performed by women. To learn more about the restaging, Dance Informa speaks with Dante Puleio, visiting assistant professor of dance at University of Florida’s School of Theater and Dance and former Limón Dance Company member, and Elizabeth Johnson, assistant professor of dance in the School and artistic director of dance 2019 (February 2019). Johnson was very excited about having someone who could restage classic Limón works, newly on faculty.

Dante Puleio.

After Puleio arrived on campus and a possible Limón work was in play, Puleio suggested the UF students perform a “mixed gender” version of The Traitor. “I’m always looking to push myself and my creative boundaries, so presented with that challenge of doing this work with a mixed-gender cast, I said, ‘I’m in!’” Puleio recounts. He has believed that it’s time to “bring [The Traitor] out of the museum and to have women dance male roles,” he says.

The rehearsal process was daunting, he shares, but ultimately incredibly fulfilling. A key factor making it a tough re-staging is a structure of “essentially eight twenty-minute solos,” Puleio explains. Each dancer truly performs their own role, their own character, within the work. The students genuinely stepped up to the plate, however, he shares. “You really saw the students grow through the process of rehearsing and performing this work, during and after — I could see them as different people and different artists,” Puleio says.

Part of that was likely the mastery of Limón work, and the students simply had to step up, Puleio agrees. At the same time, he “sort of threw the movement at them and didn’t really give them a chance to really think about it, to get scared or overwhelmed,” he shares. It also could have been the deep conversations they had about the meaning of the work — past and present — and issues of identity around this performance.

For instance, apart from women dancing male roles, a Latina student danced the role of Jesus and a Haitian-American student danced the role of Judas. In many ways, this casting challenged traditional notions of identity in the starring roles of this work, Limón himself having originated the Judas role.

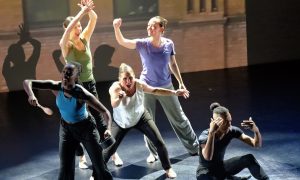

Dante Puleio in rehearsal for ‘The Traitor’ at University of Florida.

To respect the race of the student who danced Judas, a certain prop was omitted for this restaging; traditionally, Judas appears to hang himself with an actual rope at the end. “But we couldn’t have a black body hung by a noose,” Johnson says assuredly. Puleio describes how during a rehearsal, he asked the students to think about whether or not they should use this traditional prop, and they’d discuss it the following rehearsal. That they did, and, like Johnson, the students were fairly firmly thinking on the matter. They collectively decided to omit the rope and instead left the implication of the hanging to the choreography — a less literal and potentially incendiary final image that fundamentally respected the narrative of the choreography.

Johnson also believes that staging this historic work invited her theater colleagues in the School to see the dance area, and dance generally, with fresh perspective eyes. Seeing the students dance a master work with professional level sensitivity and skill confirmed that their dance colleagues are indeed preparing dance students for the possibility of a professional life in dance. “That is what we’re doing!” Johnson says with seriousness but also an air of a chuckle.

To the latter, theater professors could recognize that just as their art form, dance works share historical weight and intellectual heft. “We got a lot of ‘wow’ [from people in the School],” Johnson shares. Another interesting aspect of lineage is that UF Lighting Professor Stan Kaye, who worked closely with Limón Lighting Designer Ted Sullivan, mentored UF freshman Amber Smith through lighting the work.

Given that weight, and the success of this restaging, where to from here? A fun fact is that in next season’s performances of The Traitor, the Limón company will now use the backdrop the theatre design students made for the UF version of the work. Puleio wants to restage more historic Limón works, in conversation with the School and what’s best for students in mind. Given what he, students and Johnson accomplished with Limón’s The Traitor — making the old anew and bringing a timeless work fully into 2019 — the sky could just about be the limit.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.