The Joyce Theater, New York, NY.

August 6, 10, 13 and 16, 2019.

Taking in four nights of The Joyce’s Ballet Festival, I was struck by the diversity of what ballet can be in 2019. The ballet world is having many meaningful conversations about the art form — where it’s been, where it is, where it’s going and what it can be. For me, this festival seemed to illustrate that ballet can go as far as an artist’s imagination can wander, within the confines of a certain technical foundation — and that the wandering can be quite fruitful.

The festival was split into four programs. Kevin O’Hare curated Program A. Second in the program was Dance of the Blessed Spirits, choreographed by Sir Frederick Ashton and danced by Joseph Sissen. It was intriguing to me that Duncan-inspired work appeared in this festival, given that Duncan’s technique came from a full rejection of classical ballet’s guidelines and norms. Also intriguing to me was the variety of ways that Sissen related to the space, in relation to props.

For instance, while spreading flower pedals, they stayed mainly stationary. While holding a large, feather-light scarf, they ran, turned and leapt all throughout the space. In either way of engaging with the space, they moved with a joyful ease that made me want to get up and run, turn and leap with them. At the same time, their strength and clarity showed them to unquestionably be an autonomous, self-assured person connected with themselves, the music and the audience.

Lauren Cuthbertson curated Program B. Second in the program was the World Premiere of Gemma Bond’s Seventy Two Hours, danced by Aran Bell and Devon Teuscher. The work was memorable for its clear aesthetic and nuanced movement. Costumes (designed by Ruby Canner) faded from black to white, and dimmed lighting fell upon this fading in a way that words can’t quite do justice. The way that technical movement melded into more unexpected, less traditional posing and gesture — I was captivated.

For instance, turning led to turning lower into the floor to settle into a crossed-leg seat (“easy pose” in yoga). Once, twice or thrice that was done was particularly memorable to me; Bell lifted Teuscher from that seat to lengthen legs to a “v” shape, and then let her down to resettle on the stage. Something about this made me feel hope and a sense of these dancers’ humanity — compact in oneself, another helped her to expand and find more presence in space.

Following that was the world premiere, Darl, choreographed by Jonathan Watkins and danced by Cuthbertson. It seemed to be a meta-commentary on dance-making and the life of a performing dance artist, yet one that — impressively — seemed capable of resonating with any viewer. Voiceover described the exhaustion, elation, inspiration and frustration that can come through the whole process of making and presenting dance art. A comedic undercurrent ran through it all, in timing of the voiceover as well as movement nuances.

A technical ballet base was an undeniable, and pleasing, foundation for the movement. Yet elements of release, swing and inventive gesture (often to bring across those comedic moments) were far more postmodern — and also further humanized this woman dancing in front of us. Chasés led into tapping one foot on the floor in a quick vibration. Long arabesque lines came before turns in parallel with a bent knee and a flexed foot. The elements of classical technique caught my eyes, and her humanity showing through something more organic to the body — and dare I say, “imperfect” — kept them glued on her.

Most memorable in Program C (curated by Jean-Marc Puissant) was Kenneth Macmillan’s Elite Syncopations. Quirky signatures and unique costuming (by Ian Spurling) made distinct and impressionable characters. It felt as if what we’d see if Tim Burton were to make a dance film set in the Renaissance. Two heel-toed to travel, along with the musical beats. Another turned inward, Fosse-style. Another picked a foot upward, bending at the knee, playful and flirty.

A first group section had a strong clarity and organization, conveying that sense of a formalized “elite” gathering. The quirky individuality of each character in their duets and solos resonated with me more, but I understood the purpose of each stylistic approach within the piece. Throughout, the technique was quite present but seemingly in support of aesthetic and meaning, and not for its own sake — something I always appreciate seeing choreographers achieve.

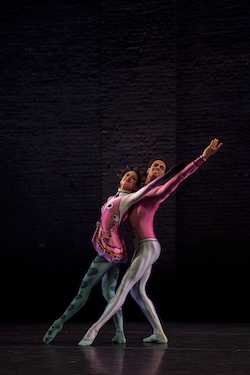

Edward Watsion curated Program D. Wayne McGregor’s Qualia Pas de Deux opened it, a memorable duet of a Spartan aesthetic and jaw-dropping technical feats. Earth tones in costumes and low yellows in the lighting (lighting design by Carolyn Wong) kept my attention mainly on the dancing; design felt like an effective support of the movement, rather than a draw of its own. Dancers Sarah Lamb and Watson executed complex vocabulary with a seemingly impossible level of spinal pliability.

For instance, Lamb curved through her spine like a snake to change from lifting a leg and her chest forward, to it facing in the other direction and her leg lifted behind her — all while supported in partnering by Watson, no hands released in the transition. The astounding nature of what their bodies could do brought an ethereal, other-worldly atmosphere to the stage. The stripped-down, honest aesthetic also allowed a harmony between the dancers to shine forth as they executed these feats. I was left thrilled, yet also somehow quite soothed.

Following that was Assume Form, choreographed by James Alsop and danced by Robbie Fairchild. It was a visual feast, yet left my mind a bit hungry — an artistic dessert, if you will. Fairchild offered the stereotypical “making it look easy”, while his strength and technical facility was also crystal-clear. Blues in lighting and his costume brought a tranquil feel, aligning with his ease and the assurance that strength can bring. Yet I was unsure of why he was moving with such size and power; what were the stakes? Perhaps that surfaces a larger question about the meaning and purpose of dance — is aesthetic pleasure for its own sake something valid for art to offer? That could be something to ponder indeed.

A following solo from Laila Diallo and danced by Lamb, All My Song, brought that substance I didn’t feel from the preceding piece. So, lucky me, all in all I felt both aesthetically and intellectually satisfied. Novel gesture conveyed clear theatricality. This was a woman delving into her strength, her softness, and when to bring either forth. How she kept my attention with movement that used up only about a quarter of the stage (versus all of the stage, like the preceding piece) was fascinating to me.

Her spinal articulation, yet also fluidity kept me transfixed. Segmentation of her body also caught my attention; in one movement phrase, her legs stopped short but her upper body kept rippling. Ballet signatures, such as a grand plié moving in and out of popped heels (creating a “forced arch” shape), were compelling accents in more postmodern movement, rather than things that stuck out as unfitting within the piece. This piece, amongst others in The Joyce Theater’s Ballet Festival, demonstrated that there is so much that ballet can be. Perhaps that’s part of its wonder.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.