Ailey Citigroup Theater, New York, NY.

August 17, 2019.

Less can be more, they say. Apply that to dance, and one could discuss how the impact of a single moving person — in his/her unique movement signature, emotional life and simply humanity — can sometimes supersede that of a large dancing group. Furthering that idea of less being more, Roberto Villanueva, executive and artistic director, and founder of BalaSole Dance Company, created a concept of linking a dance with one dancer to one word for Gamme — An Evening of Solos. The company works to “bridge the gaps in the field of concert dance.”

More for some pieces than others, the word added context and clearer meaning to its particular solo. The performances were notably committed, adept and self-assured. All solos were self-choreographed, the drawbacks of which are real (such as the difficulty of critiquing oneself dancing). Yet these solos demonstrated an authenticity to each dancer as a whole — in body and in spirit — that demonstrated a sincere advantage of making work on oneself; in truth, no one can know you better.

Kat Bark’s Not Good at Goodbyes came after an opening group number. The solo’s word was “longing”. Bark fully brought the sense of that word across; passion, pathos and pain were clear. I had to keep in mind stakes of grief and loss to not find the performance and choreography a bit melodramatic. Yet, given that theme, anything less emotive and dramatic would have felt insufficient and even inauthentic. She began facing the back, slowly rising, and in a flash faced the front. It was if she was deciding to face her grief.

A good deal of the movement was gestural, intuitive to Bark’s body, and compelling in its nuance. Much of it was also quite virtuosic, performed with striking technical facility. For instance, high-flying moments in barrel turns took her far across the stage and high above it. After a big leap to rise and turn in attitude, she landed with an arm up. She then let them arm go to let it swing, her gaze meanwhile intently forward.

That moment exemplified clear qualities in the piece — a skillful melding of the technical and the pedestrian, and a sense of her being moved by something out of her control. Indeed, one is not in control of one’s own grief; one cannot decide whether or not they feel it. I wondered if that concept of being moved by something outside of oneself could be physicalized even more clearly, with more time and exploration. I would look forward to seeing that work.

Leigh Schanfein’s solo, An Underlying Hum, came fifth. She began in a very lifted, proud ballet position. Then, in a flash, she morphed into something one might say is the exact opposite — hunched, contorted, turned inward. This early development set the tone and clarified the meaning for the piece to come. Lovely arabesques, line long and softly energized, crumpled into that same sort of distorted and inwardly-curved shape. A particularly notable instance of this change came with a falling to the floor from a ballet position held high and confident; a thud from the fall added to the drama of the contrast.

As a dancer myself, my mind quickly went to the challenge of reaching for perfection and feeling as if one has to hide or eliminate flaws as a dance artist. It is an “underlying hum” that is always with us. I connected that idea with the solo’s word, “identity”. Being a dancer becomes one’s clear identity, rather than dancing just being what someone does.

Perhaps non-dancers could see in this creative development, more universally, how we’re all reaching for perfection in our own ways and hiding our “shameful” struggles. It is hard for me to know, not being such a person. Nevertheless, Schanfein executed each movement and each shift of quality and shape with conviction and commitment; she believed everything that she was offering, and it showed.

Coming after intermission, Tyreel Simpson’s Beneath the Instinct was a compelling melange of concert hip hop and contemporary dance, wrapped in a memorable aesthetic. The black of his costume, and the caramel tone of his skin, against the red on the backdrop made his movements and shape pop. He bent deep with knees to side, lifted higher to turn, then gestured with a forearm — gaze intent and clear throughout.

At other points, there was a lightness and syncopation to his footwork, reminiscing the easy groove in much hip hop dance. He also executed a captivating blend of accent and flow, and a pleasing smoothness between the two qualities. The word for the solo was “revealing”. It felt to me as if he was standing in the strength of himself, just as he is, revealing that to the audience without fear and without apology.

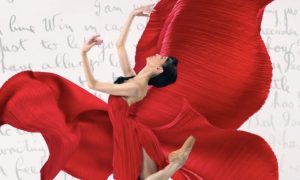

Ending out the show was Guest Soloist Stephanie Rae Williams’s Verdant. The title means leafy, lush, green and growing. Green in her costume and on the cyc reflected that sense. The Dance Theatre of Harlem company member’s liveliness in movement quality also physicalized that idea. The solo’s word was “funk”, a quality fully present in the work as well. Her hips swiveled after landing a jump, popped to one side after a turn. Stepping on both heels, toes up, after something more balletic, added sass and a pinch of quirkiness — all in all, very endearing.

Throughout the work, her timing was impeccable, bringing a very pleasing sense of harmony between music and movement. There was a New Orleans “le bons temps rouler” vibe of joy and fun. The work offered a little world that I thoroughly enjoyed entering for a few minutes. One dancer, moving in the full and clear truth of themselves, can help create such a world. For all of the wonderfully chill-inducing magic that a dancing group can offer, let’s not forget the authentic beauty of a sole dancer moving in such a way — letting us into their unique, full humanity.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.