September 27, 2019.

Center for Performance Research, Brooklyn, NY.

An astute dance artist I once interviewed discussed creating “empathetic access points” for all types of audience members — things, and ways of presenting them, to which anyone can find a point of relation. Amanda + James’s Dance + used movement, speech, music and theatrical elements to offer audience members those access points. That access was into varied emotions, some of them deep, personal and difficult, yet was presented in a universal rather than insular way. Creating and performing with openness to personal vulnerability seemed to be at the root of this unhindered sharing. Amanda + James is an “open environment for interdisciplinary collaboration [and] sparking conversations between rising artists across as wide a range of artistic disciplines as possible, encouraging multifaceted perspectives throughout the creative process.”

In My Place, choreographed and performed by Kristi Cole, set a tone for this vulnerable sharing. She began seated on a plastic tarp, moving forward and back through her torso, conveying unease. The choice of plastic made me think of artificiality — meaningfully, seemingly, not of the performer but of her surroundings. Cole was spotlit, but not quite brightly so, contributing to a mysterious and ominous atmosphere. She wore white and off-white, something with multiple possibilities for interpretation — purity or a blank slate open for the filling, for instance. She extended her legs out but stayed low, moving around the square tarp in a square pattern — agile and resolute but still uneasy.

Next to her was a pail of water, and she dunked her whole head in, gasping as she pulled it out, flipping her wet hair backward.

In her program notes, Cole referenced “using her experience as a queer woman to physically investigate….the universal human desire to occupy equal space, and therefore equal value in the world.” The physical sensation involved with one’s head dunked in water — surrounded, unable to breath, panicked — align with this feeling of having to question how much space one is allowed to take up in the world; there can be a primal, body-based anxiety with fear for one’s well-being — and even existence — in such a condition of marginalization. Cole tangibilized this feeling, in movement performance, quite viscerally and memorably.

Soon Cole rose and moved through the room — in a smoothly circular path, evoking a sense of harmony. Yet her movement, at a kinespheric (body) level, still evinced something unsettled. This combination of qualities made me think of how many people out there in the world seem to be well-adjusted and high-functioning, yet in their minds and/or in their most personal moments they are hurting and struggling. Locomoting around the stage space, Cole executed virtuosic movements, such as powerful leap and a striking barrel turn, that made me want to see more of what is was clear her body could do. Yet I was also aware that more high-flying feats could detract from the powerful emotion and message that Cole had to share.

The score, “Memory Board” by Rachel’s, shifted to Amy Winehouse’s “Our Day Will Come”. Cole moved with more strength and a new feeling of confidence — yet, still, an air of agitation. The song wound down, and she returned to the plastic tarp. She began to cry, to bawl even, head in hands. This choice felt like an acute reversal from the “happy ending” resolution norm in narrative art — a conviction and assertion that sometimes things just don’t end up alright.

Such bold truth-telling isn’t necessarily easy for any audience member to experience, particularly for those who’ve experienced severe mental health struggles or have close loved ones who have. I did wonder if a trigger warning was in order. Yet, coming from a place of heteronormative privilege, I also come to this question with humility, a desire to listen, and deference to Cole as an autonomous artist. I profoundly appreciate her adept shaping of art letting us into her world and her struggles, with such openness to being vulnerable.

Next (before intermission) came the NeurHOTics’ BETTER, a work filled with light, theatrical humor as well the vulnerability to share deeper pain. The duo, Sara Campia and Abby Price, “investigate where crippling anxiety meets unnecessary sexual behavior.” They came on bantering, puttering and cleaning up the props and wet areas from Cole’s work. They wore somewhat revealing costumes, but nothing distasteful — stomachs exposed and shorts short. Their costumes felt aligned with their humorous characters and their company’s focus.

Suddenly they realized that it was their time to perform, even though they didn’t “have time to practice….but ok, we can do this, we’re professionals” — the anxiety in their voices and bodies still apparent, however. It was a type of anxiety that can bring laughter, and the audience chuckled along. “Pump-up”, “pop”-type music came up, and they danced. It was cheer/pom, competition style dance, executed in a way that made the audience laugh all the harder. They kicked high, swiveled hips and turned with evident preparations (bringing a bit of dancer-specific humor, something “meta”, if you will). It was all intentionally and effectively humorous — even while deeper insecurity and anxiety were evident.

What felt effective in this approach was a pleasing packaging of something harder to take in, yet nonetheless an important illustration. Soon one brought out a cake — yes, a real, edible cake — and offered pieces to the audience (“anyone want cake?”). This section furthered that approach of a pleasing presentation of something harder and deeper. Audiences members laughed harder rather than accept pieces.

There was a “breaking of the fourth wall”, a direct engagement with audience members, here — moreover, one that challenged traditional decorum and norms around audience etiquette. (“Can we accept some cake? Are we allowed to eat in here? Are they really giving out cake?” some audience members most likely asked themselves.) In response, they became sad, saying “no one wants cake” and mock-crying (all humorously-delivered).

The social insecurity here was clear and poignant, even if delivered in a way that brought audience-wide laughter. The openness to vulnerability at the root of this sharing was also evident, and something I find laudable. To end, they shoved cake in their faces and threw it at each other — food fight! The stark contrast to the prior piece, Cole’s solo, was intriguing; the works were both full of vulnerability and depth, yet were delivered so differently (in terms of mood, atmosphere, pacing, and aesthetic). Each had their own valuable, rooted in vulnerable emotional sharing.

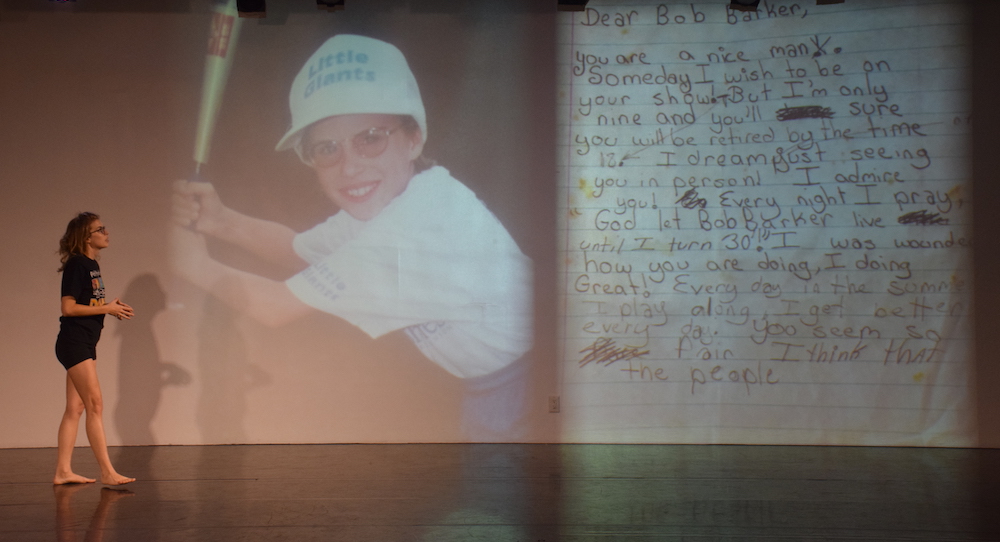

Amanda Hameline’s June 26th, 2009 closed the night, a poignant work using movement, speech, and music to delve into struggles with eating disorders, body image, and public image. To begin, Hameline walked forward in high heels, shorts short and stomach bare– evincing a high level of body image confidence. Yet later crouching inward, hiding herself and attempting to make spare clothing cover more of her, belied that confidence. Text she spoke described bulimia and (heartbreakingly) unwise responses to her behavior (presumably from a friend or family member), as well as memories from eating disorder treatment.

The performance, like Cole’s work, didn’t sugarcoat something difficult — yet maybe “sugarcoating” (maybe with actual, real cake) might make it all go down easier for some audience members. Either way, the willingness to be vulnerable is what fuels such honest sharing. These artists had that as well as an ability to shape what they presented into something aesthetically enjoyable or compelling. Concept, the right attitude, and technical facility — great art takes it all. It was all on display at this edition of Amanda + James’s Dance +.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.