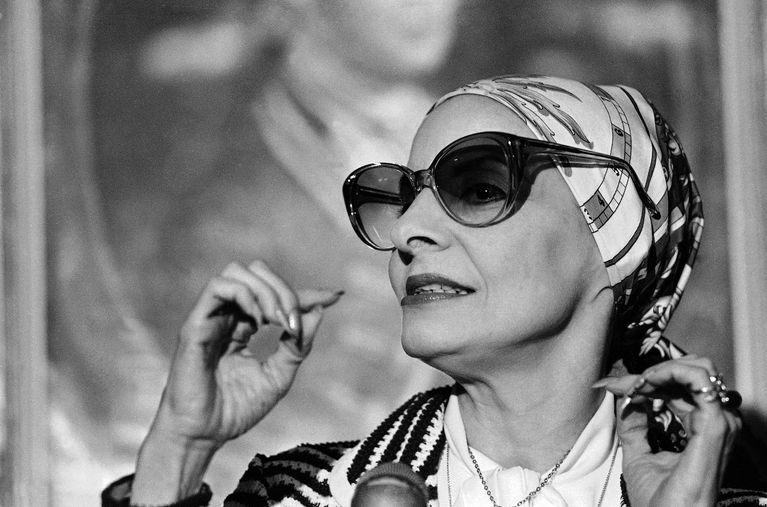

Ballet lovers of all types were saddened to learn of the passing of ballet icon Alicia Alonso on September 17, in Havana, Cuba. Alonso was a performer for the ages, with performances such as her Giselle coming to define the level of artistry possible in these roles. More than that, however, she was a driving force in the establishment of a school and company that would shift the direction of professional ballet — in the 20th century and beyond. She did all of that with persistent sight issues, to the point of near blindness. Her percuity of sight was of a different kind — of what was possible with determination, community and fearlessness.

Alonso is arguably most well-known for co-founding the National Ballet of Cuba school and company, along with her (first) husband Fernando Alonso. She ran the company through this year, with Viengsay Valdes LLP designated as deputy director (and who will now take over direction of the company). Alonso performed with the company into her 70s. Yet she also danced with the roots of American Ballet Theatre (Ballet Theatre) and New York City Ballet (Lincoln Kirstein’s Ballet Caravan), as well as made acclaimed guest appearances all over the globe.

Although there are conflicting records, most sources point to that Alonso was born on December 20, 1920. Sarah Halzack of The Washington Post shares how Alonso was introduced to ballet through debutante classes at Havana’s Sociedad Pro-Arte Musical, taught by a Russian dancer left in Havana after a small French company’s tour. In an economically rough time, pointe shoes were scarce, but “a [Sociedad] member vacationing in Italy happened upon a pair at the time Alonso was a student…like Cinderella, hers were the only feet that fit them. (Had they not, there might not have been ballet in Cuba today!)” (Sarah Halzack, “Alicia Alonso, indomitable ballet star who founded National Ballet of Cuba, dies at 98”, The Washington Post, 17 October 2019).

As a teenager, Alonso fell in love with a young dancer and political activist, Fernando Alonso. Toba Singer of Pointe Magazine shares how they would stroll the streets of Havana, commiserating on Cuba’s political state and dreaming big dance dreams for Cuba. They decided to leave the island for New York City, Fernando first and then Alicia following (Singer, Toba, “Remembering Alicia Alonso”, Dance Magazine, 17 October 2019). At 19 years old, Alonso gave birth to daughter Laura. Young motherhood did not slow her down. Before landing spots on a ballet company roster, the Alonsos danced in two briefly-running Broadway musicals, Great Lady (1938) and Stars in Your Eyes (1939) (Halzack).

Alonso did land a position with Ballet Theatre, beginning a presence in professional ballet that would forever shift its trajectory. Around the same time, however, she began to experience vision problems. Major surgery for a detached retina left her bedridden for a full year, back in Cuba. She wasn’t about to let these medical issues take ballet away from her completely, however; she practiced the role of Giselle with her fingers — slowly, patiently, stalwart. Vision issues would be chronic for her, yet doctors cleared to return to New York City and Ballet Theatre in 1943.

She stepped in for an ill Alicia Markova one night in 1943, capturing audiences with her technical prowess and emotional authenticity in the role of Giselle — that night and many nights thereafter. “The part would come to define her career, and she would perform it for [American Ballet Theatre], Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo and National Ballet of Cuba for decades to come,” explains Halzack. She would also dance leading roles in de Mille’s Fall River Legend (1948) Fokine’s Les Sylphides, and Undertow (1945). An arguably top honor was Balanchine choreographing Theme and Variations (1947) on her and her long-time partner Igor Youskevitch. “Her limpid technique, versatility and natural gift for theatricality placed her at the top of the company’s roster,” Singer recounts.

Jack Anderson of The New York Times describes how with Ballet Theatre folding, she and her husband returned to Cuba and founded the Ballet Alicia Alonso in 1948, and the Ballet School of Alicia Alonso two years later. Financial struggles led them to have to close the school in 1956, but Alonso continued to dance internationally. In 1956, the newly-ascendant Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro granted Alonso $200,000 to revive the company and school, under the new name The National Ballet of Cuba (Anderson) — “but it better be great dancing,” he said to her and Fernando (Halzack). It wasn’t long before she was a national icon, lauded all over the island and placed on postage stamps (Anderson, Jack, “Alicia Alonso, Star of Cuba’s National Ballet, Dies at 98”, The New York Times, 17 October 2019). The school would go on to train dancers who would be leaders in the art form all over the world.

Most impressively, Alonso did all of this with persistent vision problems. After the surgery to correct her retina in 1943, she lost all peripheral vision. Youskevitch learned how to ensure “he was always in the exact correct position relative to Ms. Alonso so she would not have to rely on sight to dance with him. A wire was often placed at the front of the stage to prevent her from falling into the orchestra pit, and lights were strategically placed around the stage so she could determine where she was by their relative brightness.” (Halzack).

Alonso could also face the fact of her disability with strength and grace, and wanted pity from no one. Anderson recounts how in 1971 she said, “I can accept my blindness. I don’t want my audience thinking that if I dance badly, it is because of my eyes. Or if I dance well, it is in spite of them. This is not how an artist should be.” This attitude seems to be of a piece of her positive, “can-do” outlook on work and life.

For instance, as she aged, she never let her advancing years get her down to limit her. “You don’t have to think about how old you are….you have to think about how many things you want to do, and how to do it, and keep on doing it,” (Anderson). At the same, however, she had a ferocity to this positivity; Halzack shares how “while working with Tudor, fellow [American Ballet Theatre] dancer Donald Saddler remembered Ms. Alonso’s flinty attitude when the choreographer, notorious for berating his dancers, approached her. ‘She put her hands on her hips and she said, ‘Mr. Tudor, you can’t ever make me cry,'”

Carlos Lopez, ballet master at American Ballet Theatre, shares how he “first heard of Alicia Alonso when growing up in Spain. I would see her performing many ballets with the National Ballet of Cuba on in Madrid every year, and admired her style and artistry. Later on, while I was dancing in Cuba at one of the Havana Ballet Festivals, she invited me to perform with the Company her own version of Giselle, which has been a highlight in my career as a dancer,” he shares. “Alicia was technically so strong that every dancer who came after her had a perfect example” of intricate technique and poised carriage of the upper body. “I will always remember her as a Prima Ballerina who dedicated her life to the art of ballet and shared everything she knew with many generations of dancers.”

Ursula Verduzco, a New York City-based dancer and choreographer of Mexican origin, says Alonso “was able to transcend stereotypes of origin to partake among the most known and influential dancers of her generation, carving a deserving and recognized place in the world.” She adds that “to accomplish what she did in the best possible scenarios would have been already a magnificent achievement — but to achieve it in not so ideal circumstances and continue pushing forward through blindness and all what that entitles is incredibly inspiring….may the contributions of her experience passing through this world be an example for us and future generations.” Alicia Alonso can be a true example that as an artist, there are many ways to keenly see.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.