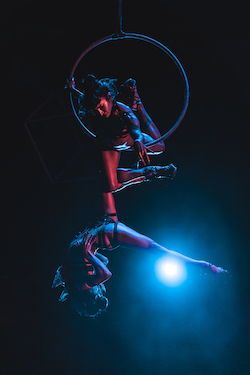

Aerial and dance artists Kyla Ernst-Alper and Sylvana Tapia got to know each other four years ago while stuck 30 feet in the air waiting to ascend inside a giant aerial chandelier as part of a group act during a run of Ziegfed’s Midnight Frolic. Now, they are starring in The Devouring, an immersive show in the Times Square EDITION, NYC, produced by House of Yes. Dance Informa was excited to speak with the duo who go by the stage name, RAVEN.

Both artists came to aerial, circus and cabaret work later in their career. Ernst-Alper, who never dreamed she would pursue aerial work because she was “super afraid of heights”, was working with Dzul Dance where the director was “beginning to incorporate circus arts and guest circus artists into his productions” when she saw Chelsea Bacon perform.

“Her technique and strength were astounding, but you didn’t notice that because every movement served the art and emotion of the piece; nothing that Chelsea did was about performing a trick,” Ernst-Alper reveals.

She began training with Jordann Baker Skipper, at the old House of Yes and shares, “The first time I went to the Slipper Room was to see two of my new circus friends perform, and I was enthralled. After years of performing long-form shows in very formal proscenium stages, often feeling like I was boring my audiences, it felt exhilarating to be in a place that allowed drinking, cheering and where the acts were short and left the audience wanting more.”

Tapia describes her pathway to aerial and circus as accidental. “I was a weary dancer looking for something to awaken my excitement again. One day, I stumbled into a yoga studio to take Silks, thinking it was just another kind of aerial yoga class. I was reignited instantly and knew that I needed to dive straight into this new form of expression.”

Ernst-Alper and Tapia both have solid technical dance backgrounds. Ernst-Alper began dancing at the age of two in what she terms an “art-rich oasis” in Brattleboro, VT, and from the ages of 12-16 lived in New York City every summer to train at Ballet Tech. She was offered a job with the company during the summer she turned 16.

Tapia danced from the age of two but did not fall in love with it until high school when she really saw where dance could go as an art form and career. “When I was a freshman, the school had newly begun a dance after-school program,” she explains. “I found modern dance and was newly inspired by Graham and Taylor and found myself surrounded by a positive community of dancers. I’d fallen in love with dance for what felt like the first time and spent my high school summers at Usdan and Eglevsky Ballet.”

“As a circus performer, it feels there are more opportunities to take gigs that pay livable wages than as a dancer,” says Tapia. “Aerialists categorize gigs as corporate, contract, nightclub, cabaret/variety and for the art. If a performer takes a corporate or nightclub aerial gig, and while on the job is asked to perform more than what had been agreed upon, there is an expectation that the performer will be paid more. That’s a mental shift when coming from the dance world, where everyone is so eager to have the most stage time, no matter the rate. Aerialists are often more business-minded than dancers. Just because we love what we do doesn’t mean we don’t deserve to be paid for our work, and that’s respected more when coming from a circus performer.”

“Circus artists generally demand better treatment than most dancers,” adds Ernst-Alper. “There are hundreds of qualified dancers competing for very few dance jobs, and if you’re talking about dance jobs that pay a livable wage, the competition is just ridiculous. Dancers are conditioned to say ‘yes’ to everything, whereas circus artists are more inclined to stand up for safety, proper working conditions and respectful treatment. A dancer who speaks up is easy to replace; a super highly skilled circus performer is not quite as easy to replace. Within aerial, there is more solidarity among performers and more respect for the artist. A large part of that respect is probably also due to the very obvious physical risks a performer takes as an aerialist or acrobat.”

Being a professional aerialist requires determination and investment of time and resources and continued good practice in every day health. “Being a well-trained dancer will give a budding aerialist a huge advantage, but there is still an immense amount of intense training necessary,” Tapia explains. “Aerial requires a continued investment in training and equipment. Proper equipment and hardware are several hundred dollars at the bare minimum and have to be maintained and replaced.”

Tapia is also a certified yoga instructor, and both artists “spend many hours studying methods for making our bodies stronger and more flexible,” she says. “We have a straps coach here in NYC, a contortion coach and seek out coaches whenever we travel. We train consistently, we do our pliés and tendus, and lately we’ve gotten more strict about taking rest days. We also eat a lot of nutritious foods.”

Ernst-Alper and Tapia stress that their work is collaborative in many ways. “RAVEN is often more than just the two of us,” Ernst-Alper says. “Any act that involves someone pulling lines or opening a motor means that we’re working as a trio. That person is an integral part of the act and thus become part of RAVEN for that performance.”

Tapia adds, “As circus performers, our ‘specialty’, as it’s often referred to, is our responsibility to create, rehearse and costume our act. At House of Yes and Slipper Room, for example, we perform acts that are 100 percent our creation. The Devouring is a contract show in which we are a dance ensemble as well as featured specialty performers. For our straps act in The Devouring, we came to the creation process with various duo straps sequences already developed for our own acts, worked with the directors to explore new ideas and riff on the already established sections, and now perform a unique act for the show that is a combination of all those elements. That’s such a different process than in dance where generally a dancer is hired to replicate the choreographer’s specific choreography.”

The Devouring is an exciting venture for RAVEN. The duo relishes that they are “always performing” due to the predictability of the show and their commitment to maintaining additional work outside the show. However, they celebrate the uniqueness of the project even more.

“One of the most exciting elements of The Devouring is that it combines highly technical dance with highly technical circus, and we’re expected to be engaging personalities on top of it all,” Ernst-Alper says. “It’s just not a common combination. We go from dancing en pointe to dancing in heels to doing a super technical aerial straps act. It’s much more common for a show that incorporates dance and circus to have dancers who can maybe do some basic aerial, and then separate specialty circus performers who can’t really dance. Our two directors, Anya Sapozhnikova and Matthew Dailey, have a lot of respect for dance, and you see their love for dance throughout the show. The Devouring is also super exciting because it is a New York cast; other shows with a similar format have imported performers from elsewhere. We’re actual New Yorkers, and that’s quite special.”

For more information, visit www.kindnessofravens.com and follow RAVEN on Instagram.

By Emily Yewell Volin of Dance Informa.