We think of cross-training as a way to strengthen and balance our bodies, when our dancing works them in the same repetitive way. But beyond the physical benefits, cross-training introduces us to new ways of thinking about movement, too. While it’s vital to have a base technique, expanding your experience should never be a bad thing. Today, we’re talking about having passions outside of dance, and how exploring other styles of movement can inform and evolve your artistry.

I’ve always been a dancer. Since the time I was three, I’ve been in the studio almost constantly. Now, I’m dancing and choreographing professionally in New York. But there was a brief interlude in my early teens when I replaced some of my hours in the studio with training at the gym, as a rhythmic gymnast.

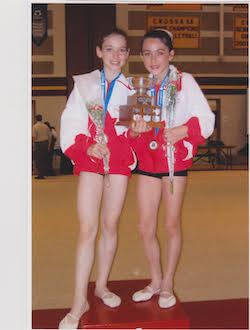

At 10, I was training 30 hours a week and going to competitions every other weekend. Over the course of six years, I won provincials individually, nationals with my duo partner and was eventually recruited to a training camp under a coach that was assembling an Olympic team. My mom (who drove me to each practice, competition and made sure I stretched when watching TV) recently dragged out a box of medals she had tucked away from my rhythmic years, and counted over 100 of them.

I loved it. But a gymnast’s career is even shorter than a dancer’s. Even in the best conditions, I would be retired by my early 20s. So at 14, when I was accepted into a professional ballet program across the country, I switched passions. My mom moved out west with me, and I re-became a bunhead.

I’d always been a dancer, but it had been some time since I had dedicated myself to it. It was a difficult transition. Because my time as a gymnast had spanned my pre-teen and teenage years, when my body was growing the most, my muscles and structure had developed for rhythmic gymnastics. I had extremely strong quads. My feet only really pointed from the toes down, and my turnout was lacking (to say the least.) While my gymnastics coaches had always pushed me to stretch my back more, my ballet teachers looked on in horror at the Gumby-like state of my torso. I had a tendency to grip and overuse my large muscle groups, and the smaller, subtler muscle groups needed for ballet weren’t properly developed. I remember thinking that maybe I just didn’t have those muscles.

But there were things that rhythmic gymnastics gave me that were assets to me as a dancer. Although it wasn’t always in the right way, I was extremely flexible. Even if my lines weren’t the most beautifully shaped, I was strong enough to hold hard positions. I was musical, performative, attentive to detail and very, very driven. This was enough to convince my teachers that I could catch up on the rest. And slowly but surely, I did. I learned how to engage my core to protect my back. I near broke my ankles trying to stretch my feet until I learned how to do it safely and effectively. But I got there. I still do daily exercises to keep my engagement and alignment in check. My hips are still set like a gymnast’s, and my quads like to takeover when my small muscle groups are tired. But I’ve learned how to use these “faults” to my advantage, too.

I have yet to meet someone in the dance world who moves like me. I’m proud of how my training has made me different. I’ve figured out how to make my body fit into the ballet mold, and retraining my muscles to do that gave me a much deeper understanding of my structure than I ever would have had otherwise. But it’s in contemporary styles where my gymnastic tendencies come through, and add a flair that makes me stand out from the crowd. When the style is left a little open, I can incorporate my old habits, and weave them in with what I’ve learned since then. I advertise myself as an acrobatic, athletic dancer, and that gets me the kind of work that I’m not only good at but I enjoy. I’m happiest when doing work that melds my two passions, and fits the body I’ve made for myself.

I heard throughout my time in dance schools that cross-training is good, but consistently practicing another sport or art form takes away from your commitment to dance. Less hours in the studio, more time spent shaping your body to some other set of ideals. “Don’t ski, you’ll get big quads.” “No, no, you’re doing it like a gymnast.”

I hear similar criticisms in the professional world. The discussion about whether a dancer’s versatility is a threat to their signature movement style is a popular one. And while I understand that the question is asked in defense of maintaining established and inherited techniques, I think the opposite is true when it comes to developing a new or personal style. Then versatility becomes an asset. What better way to discover and progress the way you move than to incorporate your other passions into it? Learning to compartmentalize our styles when asked to perform a set technique is a challenge that should be tenaciously accepted, not an excuse to stay secluded from new possibilities. And then when you do get the chance to make the movement yours, steal from other styles or sports or anything else that inspires you. Meld it in and make it your own.

Of course, different styles impose different strengths and strains on the body, and what might be good training for one could impede your progress in another. But as all dancers know, balance is key. Try boxing to add attack to your movement. Strap on a pair of heels to feel how it alters your balance differently than pointe shoes. Do it “like a gymnast.” Be as curious and as passionate about as much as you can. And then combine your passions to create something entirely new.

By Holly LaRoche of Dance Informa.