The Griffin Theater at The Shed, New York, NY.

October 13, 2019.

William Forsythe is arguably the most important living choreographer to advance the grammar of ballet. Active in the field for more than 45 years, his work has been featured in the repertoire of every major ballet company in the world. Forsythe’s impressive track record makes his personal introduction to the show all the more unexpected. He steps out in his Adidas pants and tennis shoes and performs an elaborate, comedic monologue about the importance of putting our phones on airplane mode for this quiet evening. Also mentioned in Forsythe’s monologue is his goal of subtracting sound in order to construct a community of sensitive listeners and achieve a collective intimacy, both of which A Quiet Evening of Dance do exceptionally well.

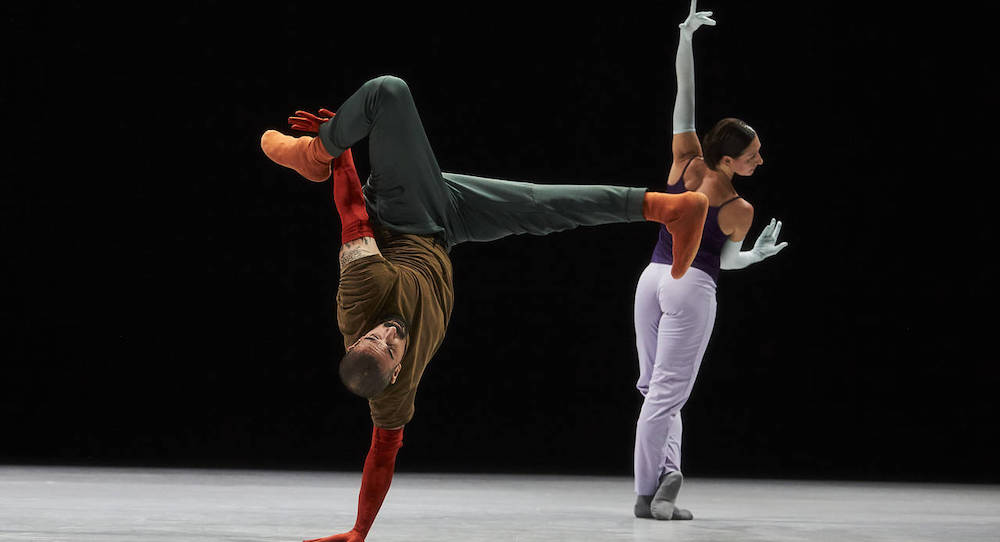

In the first half of the show, the intricate phrasing of the dancers’ breath is the primary sound score. The program opens with Prologue, where the unmistakable Forsythe movement vocabulary is introduced through a pas de duex. The couple wears mismatched, color-blocked costumes with sleek gloves and socks over tennis shoes, a look that prevails throughout the evening and gives a subtle otherworldliness to the whole affair. The dancers move almost independently from each other with calm speed, occasionally crossing arms between quick variations of light-footed, classical positions and ephemeral moments of unison that you might miss if you blink.

There is little to no pause between Prologue and the next piece, Catalogue, and this flow of motion continues throughout the entire evening, often leaving the audience unsure of when one part ends and the next begins. Catalogue is a duet between two women, and is one of the strongest parts of the show. Using mechanical gestures – cupped fingers touching shoulders and hips, isolated head tics – the movement builds in complexity as the piece goes on; the gestural vocabulary builds in both quantity and intensity, gradually becoming less angular and robotic, incorporating the lower body, and taking on a smooth, rounded quality.

For the majority of the piece, the dancers are stationary, never venturing beyond the center of the stage, but in the later sections the dancers move forward and backward, tentatively exploring other parts of the room in the characteristic, Forsythian mode – a flurry of altered tendus and augmented pas de bourrées interspersed with spurts of petit allegro.

The almost unison of the two dancers (and the way relationship is mirrored in their similar, but distinct costumes) in combination with their sidelong glances at each other give the impression that one dancer (who just so happens to be the younger of the two) is learning from the other in real time. Although it would be nearly impossible to improvise with such precision and speed, the way the dancers react to each other feels similar to a tightly structured improvisation. Not only does Catalogue toe the line between “live” creation and prepared movement, but it calls attention to the overlap of conversation and performance. Although the dancers face the audience almost exclusively, a clear sign of performance, the concurrence of their respective choreography undeniably invokes the give and take of a dialogue.

The glimmers of unison are the most striking moments of Catalogue. Toward the end of the piece, the dancers pierce the breathy quiet with a perfectly timed clap. In this moment, Forsythe’s unique voice manifests itself with resonance.

Up next is Epilogue, a series of solos and duets set to neoclassical piano music characterized by dizzying direction changes, a wide range of facial expressions (e.g. unapologetically showy, serious, playful), and nimble footwork. Although it lacks the cohesion of Catalogue, the audience is struck by the sheer amount of material that can be produced within the distinct world that Forsythe has constructed.

According to Forsythe, the final piece of the first act – Dialogue (DUO2015) – has been in the works for 20 years, evolving as new dancers step into its two roles. This version features Riley Watts, a male dancer based in Portland, Maine, with the most flawless technique imaginable, and Rauf ‘RubberLegz’ Yasit, the LA-based contemporary b-boy Instagram icon. The piece has an air of casualness that its predecessors do not. Many of the choreographic patterns from Catalogue (e.g. conversational choreography, flashes of unison) are employed, but in a less formal, more human mode that unabashedly whips across the stage leaving no inch of marley untouched. Dialogue achieves humor through facial expressions and the juxtaposition of two opposing characters who nevertheless seem to share an almost brotherly connection. Despite their differences, they are ultimately on the same page.

Following intermission is one longer piece, Seventeen / Twenty One. I must admit that after the undulations of the first half of the show, the piece felt comparatively uninflected and drawn out. Seventeen / Twenty One marks a definitive mood switch from the first act, coloring the air with the harmonies of powerful string instruments. Quick blackouts mark the end of one section and the beginning of the next and while the choreography sometimes directly coincides with the music, it is primarily independent from the bright, celebratory melodies. It is unclear what the dancers’ relationships are to each other, and equally unclear whether Forsythe is interested in these abstruse relationships beyond their spatial organization. RubberLegz’s floorwork is again a highlight, and serves as a welcome interruption to the classical tropes that are at the fore. The entire cast comes together for the first time during a vibrant, short-lived finale that ends with a synchronized bow.

With elements both human and alien, both classical and avant-garde, A Quiet Evening of Dance is genre-defying. Forsythe’s work is refreshing in comparison to a great deal of contemporary concert work for one crucial reason. I often see dance shows and think, “I know how they constructed that phrase,” or “I know what improvisational exercise this section was born out of.” With Forsythe, both dancemakers and general audiences are left asking themselves, “how did he come up with this?” Forsythe’s ability to keep audiences asking this question is the underlying reason for his unabated success.

By Charly Santagado of Dance Informa.