The Actors Fund Theater, Brooklyn, NY.

February 13, 2020.

In this post-postmodern age, both the modern and the classical are celebrated and critiqued. All styles and qualities are fair game for exploring. The conventions and values that classical and modern works reveal — be they presented together or apart — speak to issues such as representation, privilege, and power. We can see the ways in which our culture has shifted and evolved, and the ways in which it hasn’t. Brooklyn Ballet’s Revisionist History II boldly spoke in these ways, through concept and other creative choices.

A restaging of the iconic Pas de Quatre featured four women of color (Paunika Jones, Miku Kawaruma, Christine Emi Sawyer, and Courtney Cochran), a powerful statement about representation and race in the ballet world and beyond it. Following that was a quartet with four men of color dancing different styles of hip hop — about as different from the original Romantic ballet work as one could get while still in the same structure. The night closed with Intersection, a work speaking to the modern urban condition of constant motion and lack of true community — contemporary ballet with a solid classical base.

Pas de Quatre began in that archetypal tableau — levels, gazes and port de bras wonderfully crafted for aesthetic harmony as well as a balance of connection and solitude for each dancer. The dancers’ committed focus was immediately clear. Their costumes were in the same theme (in color, design style, material), but each dancer wore something slightly different — giving each a concrete sign of individuality.

They moved through solo, duet, and group sections, all offering their own movement quality and aesthetic. One dancer was notably gentle and clear. One came with a sense of focused, accented attack. Another had a somehow soft sense of groundedness. Still another had a distinctly jovial, coy presence, and a sprightliness in her movement.

There were several falters in turns, and I did wonder if choreography could have been altered to prevent this. It did detract from the lovely classical choreography and unfaltering presence of the four dancers. On the other hand, perhaps it was due to venue conditions — such as a slippery floor or lighting making spotting hard.

On the whole, however, the dancers offered bold, fierce individuality as well as harmonious grace. They were fully attuned to their group and partners. I could hear their pointe shoes across the stage. The strict technical teaching says that you don’t want to hear that, but this effect offered another auditory layer that I enjoyed. All formations were structurally clear and visually enjoyable.

The work ended in a tableau, as it began — the four women as their own unique spirits but in joyful, harmonious community with each other. I reflected on the power of the imagery here, four women of color dancing in an iconic work, that iconic nature specifically white. I wondered what child of color — or person of color of any age, for that matter — who came to the show might for the first time see themselves in ballet and be inspired to put on ballet flats themselves.

Quartet followed that, with choreography from the dancers and concept from Lynn Parkerson (Brooklyn Ballet’s Artistic Director). Four men of color (Michael “Big Mike” Fields, James “J-Floats” Fable, Bobby “Anime” Major, Ladell “Mr. Ocean” Thomas) danced in a structure similar to Pas De Quatre — each in their own signature under the larger umbrella of hip-hop movement. One moved in a “flexing” style, bending and placing joints in ways that did not seem humanly possible. One “popped and locked”, accenting with strength and then releasing. Another tensed muscles in his chest, buttocks, and arms in comedic, lighthearted ways, making the audience chuckle. Yet another had a smoother, more lyrical style, smoothly waving and flowing through his joints with the beats.

Interestingly, Pas De Quatre translates from French as Quartet. They began and ended in a tableau of varied levels and shapes, just as the prior piece had. As a variation on sections in Pas de Quatre when the dancers bourreed around in a circle, facing outwards, the men did the same but on flat feet and alternated levels with their arms bent at the elbows (which was visually and energetically pleasing). The music began and ended in the same score as Pas de Quarte, yet in between “R & B” and hip-hop tunes accompanied the dancers.

There were also more humorous and theatrical moments in this work than in the prior piece, underscoring the increased place of overt theatricality in modern, post-modern, and post-post modern dance. Yet like the prior piece, it powerfully questioned classical and social conceptions of dance art through offering an enjoyable, well-done alternative — apart even from being in a very similar structure.

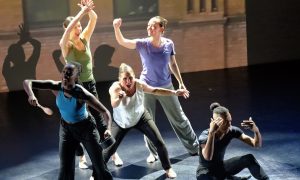

Intersection followed, a thoughtful and well-crafted work on the modern urban condition of constant motion and lack of genuine human connection. Parkerson choreographed this work. Dancers entered and exited, shifting through paired sections. Audio of messages from the MTA (New York City’s transit system) rang through the theater. Dancers wore stylized everyday clothing, each in a slightly different outfit (though with some similar pieces and patterns). All of these choices and qualities coalesced to form the illustration of people busily and quickly moving around an urban space.

The women wore pointe shoes and danced in a more classical style, while the men danced in more of a hip-hop style. Parkerson called upon linear aspects in both movement styles to create compelling partnering — such as a motif of men with their arms straight out as support and their partners arabesqueing behind them. At other times they moved their torsos through squares that the men also made with their arms. Another memorable motif was partners facing each other and the women rolling up to full pointe and then back down to flat — simple but clean, intriguing, and memorable.

The dancers continued to move through different formations and groupings, those MTA intercom messages intermittently playing. When they weren’t, live cello (by Malcolm Parson) and drums (by Killian Jack Venman) accompanied the dancers. The resonant tones of these instruments brought a sense of something deeper underneath the outward presentation of commuters in hustle-and-bustle mode, and the myriad sensory stimuli present for urban-dwelling people as they commute.

Dancers exited individually and in groups, and the lights went down. The work ended, but it had left a new vibration in the room. Classical and modern elements in meaning and aesthetic had together truly left an impression. We can honor the past while we work to correct its harmful wrongs, as best we can. Art can be a place to start.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.