Alla Kovgan is the writer, director and editor responsible for bringing the work of Merce Cunningham to life in the stunning, new 3-D film, CUNNINGHAM. By her own admission, she is not a dancer, and Cunningham was never even one of her favorite choreographers. And yet, before she could even start filming, she spent four years doggedly searching for the funding to bring this ambitious project to life. Along the way, she would adopt Cunningham’s motto as her own: “The only way to do is to do it.”

Although Kovgan had long admired filmmakers like Charlie Atlas who collaborated with Cunningham, she traces the origins of this project back to 2011. The Merce Cunningham Dance Company was performing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as part of its farewell Legacy Tour, and Kovgan was in the audience. As she was watching, it struck her that 3-D technology could make it possible to capture the complex spatial relationships of Cunningham’s work on film. After the show, she reached out to Robert Swinston, Cunningham’s longtime assistant who was named Director of Choreography upon Cunningham’s death in 2009. With Swinston’s enthusiastic support, Kovgan charged ahead despite mounting obstacles.

While Cunningham is an icon in the dance world, Kovgan quickly found that many in the film world, including would-be funders, didn’t have a clue who Cunningham was or why his work was important. At best, people would recognize the name of one of his collaborators like John Cage or Robert Rauschenberg or, more likely, Andy Warhol. Instead of getting discouraged or questioning the project, this apparent ignorance of Cunningham’s accomplishments motivated Kovgan to keep pressing forward.

As an experienced filmmaker, Kovgan is accustomed to defending her vision in the face of critics, but she was a bit surprised by level of skepticism she faced about her plans to use 3-D technology. The legendary German director and producer Wim Wenders had recently garnered much acclaim for his incorporation of 3-D into his film, Pina, about choreographer Pina Bausch, but its success was attributed to Wenders’ special genius despite its reliance on 3-D. However, as Kovgan explains it, 3-D technology itself functions in a way that makes it the perfect vehicle for translating concert dance to film because it “slows the audience’s perception.” In other words, the brain has to work harder to process the images being seen which has a calming effect on the viewer. “This is great for Merce’s work because it causes the audience to slow down and really take in the details in long shots,” Kovgan says.

Having studied Cunningham technique myself for years, I have a deep, embodied memory of the movement language upon which the works in the film are built. As I watched, those memories were rekindled in a way that I usually only experience when I am watching the company in live performance. Maybe it is the magic of 3-D, or maybe it is just Kovgan’s own brand of special genius, but, for me, the film evoked the tensions and textures of Cunningham’s work with more resonance than even Cunningham’s own forrays into dance on film.

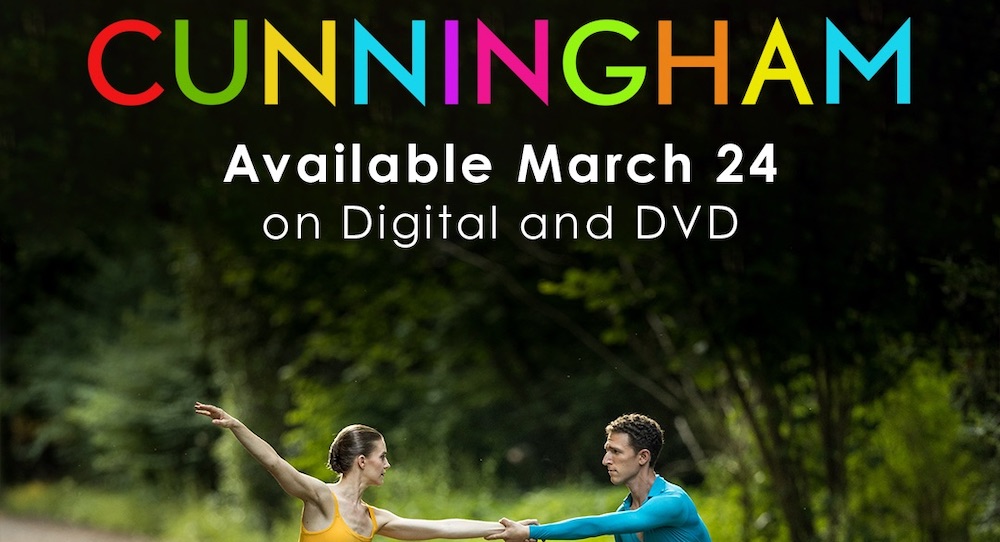

Watching the film unfold, it is hard to believe that it was shot in just 18 days. With 14 dances embedded in diverse settings, from a forest glade to an industrial zone rooftop, each of Cunningham’s works is treated as a world apart from one another and from the rest of the film. The effect is mesmerizing and immersive, even on the small screen in my living room.

Although Kovgan had originally hoped to shoot the film in New York City, the cost proved prohibitive, so ultimately, they just had just one day in Cunningham’s hometown during which they shot several rooftop scenes by helicopter. Two of Cunningham’s most iconic works, Summerspace (1958) and Rainforest (1968), were shot on a soundstage in France, but the majority of dances were shot on location in Germany over 15 days as the cast and crew worked their way across the country. In order to make this tight schedule work, Kovgan, her film crew and the dancers had every movement and corresponding camera angle coordinated down to the second.

When I asked Kovgan about the process of location scouting, she joked that she could write a whole book about it. For just one of Cunningham’s work, Crisis (1961), Kovgan and her crew visited 15 potential wooded locations, taking detailed measurements of each space. They used those measurements to create virtual models of each space complete with a virtual dance to inhabit it. Once they chose the final location, the shoot was storyboarded so precisely that the dancers and film crew just had to execute the plan on the day of the shoot. By necessity, most of the dances in the film were shot in just one day, which is an astounding feat.

Over the course of the film, Kovgan slowly increases the length of the dance sequences, from mere seconds to more than four minutes, in order to lead the audience deeper and deeper into the richness and complexity of Cunningham’s work. At one point in the film, Cunningham is seen in archival footage answering the question, “How do you describe your dances?” His response is quick and simple: “I don’t describe it. I do it.” Like Cunningham, Kovgan wastes little time telling the audience about the work; instead, she invites the viewer into the space between the dancers and leaves us to take what we will from the experience.

Of course, the film is more than a patchwork of 14 dances; Kovgan also creates rich collages of archival materials that provide glimpses into Cunningham’s motivations as both a man and an artist. Inspired by Cunningham’s own collage work in Changes: Notes on Choreography, Kovgan layers celluloid photos, slides, Cunningham’s own drawings and archival film in a way that intentionally evokes Joseph Cornell’s shadow box assemblages. The effect is a powerful one, lending the images of the archival materials an almost visceral quality. It reminded me of the feeling of rummaging through the Cunningham archives myself when I was an intern there many years ago.

Ultimately, Kovgan says the film seeks to demystify Cunningham and his work, taking viewers on a journey through Cunningham’s life and work as an artist as it evolves over time. Kovgan makes it clear that she wasn’t interested in making a typical dance bio flick with lots of talking head interviews with and about the subject. She insists, “It isn’t meant to be educational. It is an experience, evocative. The dances aren’t filler; they are essential.” Instead, Kovgan wants us to be transported into Cunningham’s work, and she succeeds. Immersed in world of CUNNINGHAM, the rest of the world receded for a while, and it was a welcome respite for me.

Like my fellow dancers around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has separated me from my studio, my students and my dance colleagues; we meet only online now. Kovgan herself was on lockdown in New York City when we spoke, and she offered up these words of encouragement to artists at this time: “It is always the time for art. When everything else is in crisis, what saves us is the art. It is what is left of us. Presidents come and go, but our art perseveres.” As Cunningham would say, “Someone has to do the work,” no matter what else is going on in the world. Kovgan has certainly done the work, and we are fortunate to have a film like CUNNINGHAM at such a time as this.

By Angella Foster of Dance Informa.