July 31, 2020.

Online, on YouTube.

Among the many performances presented in the new quarantine norm of livestreaming, Diavolo’s This Is Me: Letters from the Front Lines offers some much needed focus on two things. The first is thoughtful collaboration with the filmmakers who recorded the piece. And the second is an honest and unromanticized approach to capturing the moment we’re living through.

I’ve seen too many interpretive, “political” pieces vaguely reference the virus, or quarantine, or other current affairs in an unhelpful and uninformed way. Diavolo, commissioned by the Soraya Center for the Performing Arts in LA, did the opposite. In a piece about what it means to be a public hero, they centered veterans and doctors, having them tell their own story. The dancers supported, contextualized and underlined key moments in those stories.

The Artistic Director of Diavolo, Jacques Heim, is no stranger to this kind of work. For the past five years, his company has been engaged in The Veterans Project, an initiative created by Heim to help restore veterans physical, mental and emotional strengths through dance. “Sometimes you’re making a piece just for the sake of making a piece. And it’s entertaining. But eventually you start to wonder, ‘What am I doing here? What’s the purpose?’” Having already worked with soldiers from the front lines, Heim was able to work with first-responders in much the same way. Both share duty, responsibility for the lives of others and the accompanying mental stressors.

Heim approached addressing those experiences with the empathy of an artist. Through writing letters, the veterans and medical professionals featured in the piece and rightfully referred to as warriors, were able to talk through their first-hand accounts without being imposed upon. And then from those letters, Heim created a piece that included them in the creative process, staying true to the intentions behind their words.

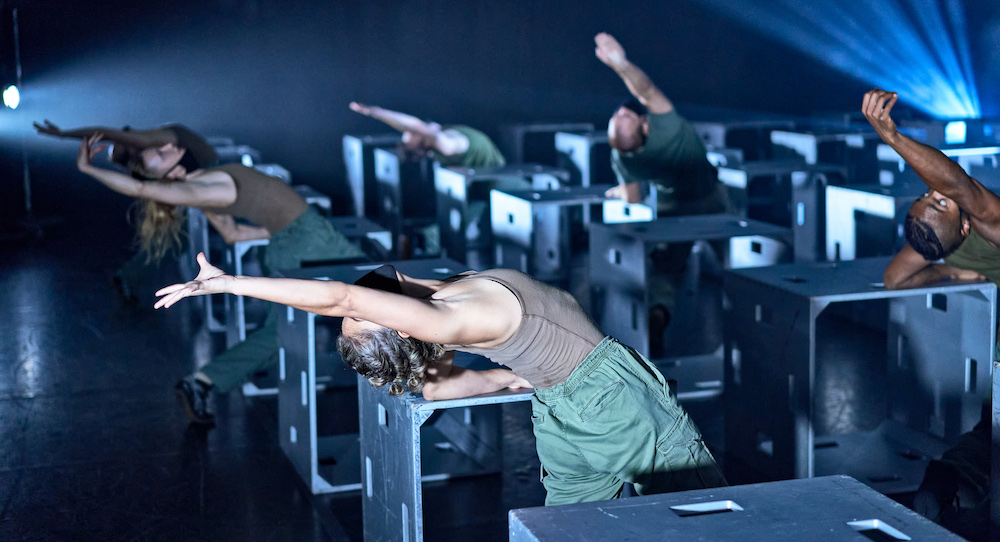

Diavolo dancers used giant architectural structures of wheels, cages, ramps, forests of poles, and stacked cubes with a dancer in each made to look like a fully occupied apartment building to portray places, situations, obstacles and other details of the warriors’ letters. The dancers climb, fall, flip and vault the structures in death defying movements, just as the warriors “defy death a little longer” (Tyler Grayson, U.S. Army) all while wearing masks.

The warriors are in and amongst the fray of dancers, speaking their letters out loud. Some join in on the chaos, more active in their movements. EMT Lucas Haas climbs the structures and lifts or drags dancers to safety. La’Vel Stacy, U.S. Navy, moves through a phrase inspired by his letter, dancing the intentions and emotions behind it as only his experiences would allow him to. Had the phrase been set on a dancer of the company, it would have lost the depth of its meaning. And when a dancer, France Nguyen Vincent, is centered in the story, she isn’t dancing as a public hero or trying to take ownership of that narrative. She is herself, stuck at home, wondering what it feels like to be fighting on the front lines and struggling with what she can’t help but feel is inadequate inaction on her part. She acts as a through-line for the piece, a character whom the audience can relate to. The role she plays in relation to the warriors of the film is our role in relation to the medical professionals outside right now: support.

Hearing the military veterans’ stories helps us grasp why that role of support is so vital. Air Force Captain Shannon Corbeil, who worked in Intelligence and dealt with cyber threats, is used to invisible enemies. She knows how difficult it is to stay inside while others are risking their lives. “But we all have our missions. My job is to make sure others have what they need. Support the fighters; that’s my role.”

Letter after letter gives us insight into all the different kinds of support we can give. This fight requires planners like Dr. Sasan Najibi, a vascular surgeon and chief of staff at Providence St Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, CA, to redesign hospital layouts and protocols in order to best protect its patients and staff. It takes protectors like Christopher Loverro, who served as a civil affairs sergeant in Iraq, taking care of the civilians in the battle space. It takes fair-minded people like Tyler Grayson, previously a Sergeant and Combat Medic in the army and now a senior registered nursing student, and La’Vel Stacy, previously a culinary specialist in the Navy, who see injustices in the systems that are meant to protect people. It takes teachers, donors, voters, protestors. It takes clothing companies becoming mask-makers, and breweries repurposing their alcohol to make hand-sanitizer. And yes, it takes EMT first responders like Lucas Haas, and ICU nurses like Mariella Keating, and every other warrior featured in this piece and on the front lines. But the rest of us don’t get off scot-free. As artists, it takes us to inspire others.

In a time when many of us sheltering at home are finding distraction in escapist art (which has its own uses), it’s wonderful to see such a thoughtfully created example of art that engages its audience and mobilizes their emotions for a greater cause — even if that cause is “just” staying home. It’s an interesting addition to the great debate of art for art’s sake. The prompt is this: in times of civil unrest or widespread disaster, is creating art while people are lacking more basic needs an inherently selfish, privileged act? Artists have proven time and time again that art is a necessity in even the most turbulent times. Songs, dances and other outlets for creativity have historically helped carry us through the worst of hardships. Throughout this pandemic, we’ve seen both kinds of art do the work they’re best at. Escapist art has helped comfort us while staying inside, and engaging art like This is Me has helped inspire us to continue to do our part by quarantining, social distancing and wearing our mask. The warriors whose stories are featured in this piece are the people we need to support right now, and Diavolo succeeded in finding the artistic embodiment of that.

Watch This is Me: Letters from the Front Lines.

By Holly LaRoche of Dance Informa.