Here’s an upside to the dance world finding its footing in the new normal: we’re all learning the steps together. While I’ve been teaching livestreamed classes and running remote rehearsals, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was doing it “right.” Is there a “right” way? Luckily for me, Emmy Award-winning choreographer Mandy Moore (La La Land, Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist, So You Think You Can Dance) and Emmy Award-nominated, beloved Steps on Broadway teacher Al Blackstone (also choreographer of his recent production, Freddie Falls in Love, among others) were happy to help. Here’s what they have to say on working remotely as the artist at the front of the room.

Moore and I last chatted a few months into quarantine, when her film Valley Girl was released. She had mentioned that she’d been working on other projects since the lockdown had started. All aired now, her quarantine content so far includes the Facebook Messenger Rooms commercial, a Stella Artois commercial and two Disney sing-alongs. She’s been busy, to say the least.

“I feel so fortunate,” Moore shares. “I was like everybody else, everyone’s jobs within days were just gone. So I feel super lucky to be able to do something, even if it’s virtual. Because that’s a very different process, obviously.”

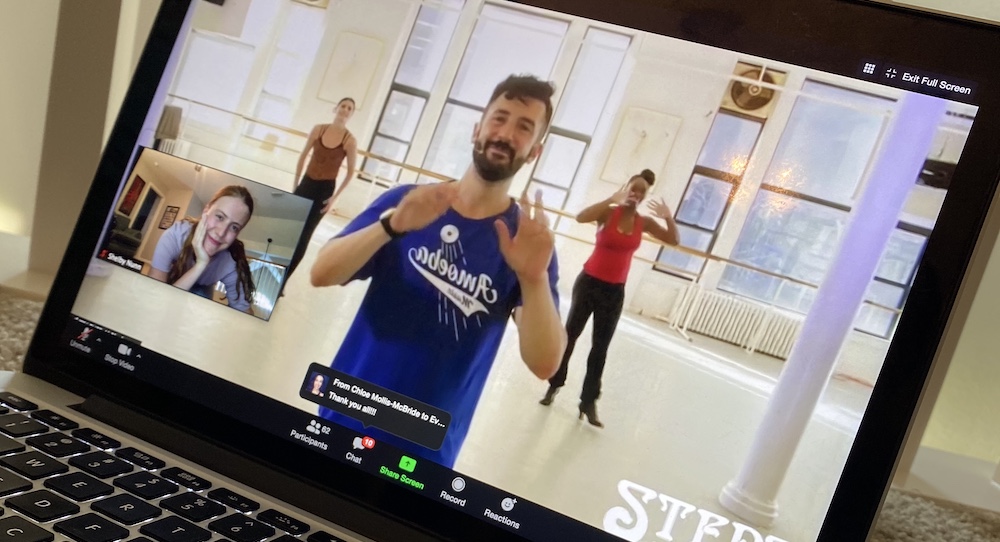

Blackstone hasn’t been idle either. His theater jazz class at Steps on Broadway is a staple in many New York dancers’ schedule, and a pandemic wasn’t going to change that.

“As soon as it was possible, I began,” he says. When asked if teaching through Zoom has affected the structure of his class, he said in some ways, no. “I’m still teaching my same warm-up. Although it’s a shortened version, because I think it takes more time to learn choreography in this setting. I’m still teaching a phrase.” Obviously, across-the-floor work isn’t doable, but Blackstone says the rest has proved adjustable. The acting components of theater jazz and the fact that New York dancers are used to tight quarters has helped him transition his class online. “I was really thrilled by the challenge of having to create choreography that was still satisfying and challenging that didn’t travel, didn’t require a lot of space,” he says.

Both Moore and Blackstone note the importance of clear communication. And Blackstone’s found a way to turn that challenge into an opportunity. “A lot of people are taking class wearing earbuds,” he says. “I think about the idea that I’m talking directly into their ear. Which is in some ways so intimate. In a format that feels like it’s not, I’ve found that there is an intimacy there.” He underlines being conscious of the timbre of his voice as a way to connect with the dancers.

Concerning communication throughout the choreographic process, Moore has great tips. “This sounds obvious, but it’s less show-and-tell. It’s more discussing and directing. You have to be really smart when you first create it. You’re not going to be able to make a lot of changes. You also have to manage expectation. It can’t be too intricate. You have to think bigger picture. You rely on the talent to fill in some of the blanks, because you’re just not there to physically show them.”

That proves the superpower of smart dancers. Working with a cast that knows how to make it work is more vital than ever. Moore adds that it’s her job to be a guide and support for her talent, but that at the same time, “they’ve got to be the ones to make it happen.”

Musicality on Zoom is also a shared issue. Coming from a post-modern background, I’m familiar with setting movement to music only after it’s been choreographed. But never until now have I used that approach in commercial styles. It seems that Moore and Blackstone are using similar work-arounds.

“My approach lately, and this might change,” Blackstone reveals, “is I’ve started to give dancers permission to create their own musicality, to take ownership of it. And maybe that’s a new way for them to build musicality, rather than having it given to them. I’ve been thinking that I want to start making movement and changing the music up.”

Moore ran into the same sound problem. “It’s the worst,” she says. “It was a huge issue on this Facebook commercial [filmed on Zoom]. I couldn’t find where people’s downbeat was. I had them all clap on their one count, so that I could see in the nine boxes where people were in the music, and so post-production could understand their timing.”

Her solution differs slightly from Blackstone’s. “I realized I can’t be so specific with it,” Moore says. “It needs to be movement that can transcend timing. Not ‘one-y-and-a-two-y’ but finding movement that tells a story, that the music can become a soundtrack to.”

As for what they miss most about in-studio sessions? Blackstone discusses the sense of community, and how he’s been trying to humanize online training. “This is one of the dancers’ only opportunities to feel like they can be together. For awhile, there was a heaviness to that, so much pressure to provide something like what people had before. But then I realized that it’s not about me at all. They’re here for one another, and for the class. I’m happy they can have that space.”

He interviews new students, encourages them to encourage one another through Zoom’s chat feature, uses the spotlight feature to change up the screen and highlight dancers, and “every 10 minutes, I make everyone come really close to the camera and put themselves on gallery view and wave at each other. Because sometimes you just forget that we’re all there.”

Despite the difficulties, Moore says it’s pushed her as a choreographer, forcing her to cut down on frills and focus on her choreography’s role within the bigger context of the commercial or show. “Because it’s never about your choreography, as a choreographer, but in this moment, it’s really not about your choreography,” she explains. “It’s about execution, making sure the dancers are comfortable with what they’re doing, and that the director is happy with what they’re looking at. You have to trust your gut and realize that it’s not worth a crazier, more creative step. Because it might go down in flames.”

Quarantine dancing is definitely different from the work we usually make, but not in a good or bad way. Out of necessity, it’s become more focused, bringing a simple clarity to the movement. It’s also freer, in a sense, giving dancers the chance to explore musicality on their own terms. Dancers, teachers and choreographers alike and at every level are figuring it out as they go.

“None of us really know,” Moore says. “We’re all just trying to do the best we can. People just want to dance however they can, and we figure it out. Little hustlers, all of us.”

By Holly LaRoche of Dance Informa.