Jacques d’Amboise was a dance icon, gracing stages with the New York City Ballet (NYCB) across the world for decades. Graciousness and generosity characterized his career, in multiple ways. For one, he danced with a unique vibrancy, giving all to audiences and the work he was dancing. For two, he was deeply passionate about access to arts education — and a notable part of his legacy is millions of children having that access when they otherwise might not have.

d’Amboise passed away on May 2, at 86 years old. His daughter, actress Charlotte d’Amboise, shared that complications from a stroke were the cause. The dance world is fondly remembering that unparalleled legacy of generous dancing and making the gift of dance more widely accessible.

Finding something magical and very hard to do

d’Amboise was born in 1934, in Dedham, Massachusetts (a suburb of Boston). It being the height of the Great Depression, his family soon relocated to New York City for more work opportunities and enrichment possibilities for the children. His mother — whom he referred to as “The Boss” — enrolled him in ballet at seven years old. She told him that ballet was “magical and very hard to do,” D’Amboise shared in his 2011 memoir, I Was A Dancer. After a few months, he and his sister were dancing at the School of American Ballet, under a certain now-famous Russian expatriate — George Balanchine.

By 12 years old, he was dancing with the precursor to NYCB, Balanchine’s Ballet Society. Three years later, in 1949, he became an inaugural member of the newly-formed NYCB, as the company’s only “hometown” male dancer. He then danced with the company for 35 years, dancing pivotal roles in ballets from Western Symphony to Concerto Barracco to Afternoon of a Faun.

A multi-dimensional muse

d’Amboise partnered some of the ballerinas most well-known in the company’s illustrious history, including Maria Tallchief, Diana Adams, Tanaquil Le Clercq and Allegra Kent. He might have also been responsible for Suzanne Farrell coming to Balanchine’s attention as a young dancer with potential beyond dancing in the corps. Later, as he coached young dancers, his love for the art form and deep wisdom was undeniable. Balanchine, his teacher at a young age, remained a fundamental part of his creative life throughout. The pioneering choreographer’s muses were largely women, yet he created a number of roles for d’Amboise, including in the famous ballets Stars and Stripes and Jewels (1967).

d’Amboise danced with a “youthful, fervent heat,” says Gia Kourlas, chief dance critic at The New York Times. His athleticism was striking, but he also danced with an interior life — going beyond the technical “tricks” to express mental and emotional depth, Kourlas adds. Dancing Apollo, he executed angular choreography with precision but not tension. His physical strength was clear, yet so was a sort of soft receptivity. At a time when many men considered ballet too “soft” or “effeminate” for them, d’Amboise made clear that strength and softness aren’t mutually exclusive.

In another defiance of binaries, in a television appearance with family members, he demonstrated a striking work ethic but also the ability to let loose and not take himself too seriously. Dancing, acting and singing in Seven Brides, Seven Brothers (1954) and Carousel (1956), as well as on Broadway, he also didn’t seem to put much stock in the idea that ballet is “high art” above other forms of theatrical entertainment. He seemed to love to dance, and wanted everyone else to know its magic, too — and that’s what mattered.

Dance reaching far beyond Lincoln Center

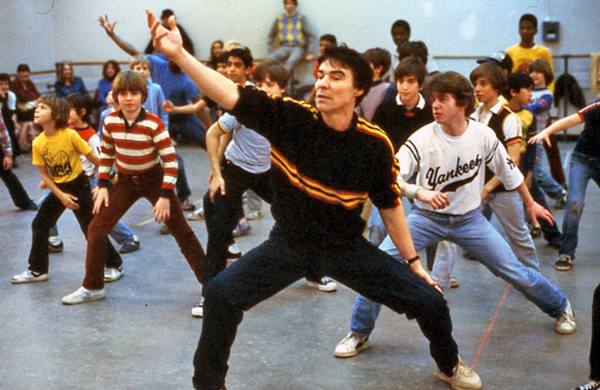

Along with his wife, Carolyn George d’Amboise, d’Amboise formed National Dance Institute (NDI) in 1976. While still a NYCB principal, and thus handling a rigorous schedule and energetic demand, d’Amboise would boldly approach school administrators and offer to teach dance classes for free.

Apart from notable generosity, some may see confidence bordering on hubris in that approach. Yet, when D’Amboise was offered a book deal at 20 years old, he is said to have responded, “Ridiculous! I haven’t lived yet!”. More than hubris, it seems that D’Amboise had a deep self-awareness — knowing how, when and where he could best contribute and make a difference.

NDI has grown far beyond those first bold asks. Each year, the organization engages more than 6,500 children in New York City, and more than 60,000 globally. Since its founding, the organization has reached over two million children. Making ripple effects through continued work in its method, NDI has trained over 1,500 educators and teaching artists. Post-mortem surveys attest to NDI programs’ ability to boost self-confidence, creativity, social-emotional intelligence, and many more skills and attributes essential for life-long success.

d’Amboise would note how as a young man, dance kept him from getting into trouble; when not dancing, he would spend time with a youth street gang. He wanted to pay forward the difference that dance made in his life, through dance education — training and exposure not necessarily for a professional life in dance but to build stronger, more creative, more capable people. “The goal isn’t to churn out top-notch dancers; rather, [NDI] strives to give students a sense of discipline and expose them to an outlet for creativity and self-expression,” notes The Washington Post’s Sarah Halzack.

d’Amboise’s life exemplifies how dance continues through generations through generous legacy — the cyclical passing down of knowledge and skills. Yet, d’Amboise is unique in how far and wide he shared his knowledge, proficiencies and passion for the art of dance. We can’t truly know how deeply impacted countless lives have been as a result — but we can know that such impact is something to treasure and be profoundly grateful for. Rest in power, Jacques d’Amboise, until we dance with you one day again.

For more information on National Dance Institute, visit nationaldance.org.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.