Auditions — they’re nerve-wracking and inspiring all at once. Unfortunately, for some dancers, they can also feel disrespectful; directors may, albeit likely unintentionally, run things in ways that don’t honor dancers’ time, practical needs and feelings. Given the realities of dancers’ lives, practical resources and expectations might be quite fragile matters — and such disregard can have quite a harmful impact.

To discuss how directors can improve their “audition etiquette”, and therefore avoid that kind of unfortunate impact, Dance Informa speaks with a choreographer on how she does as much, Megan Curet of Curet Performance Project, and two dancers on their audition experiences — Ursula Verduzco and Kristen Hedberg, both NYC-based. And here we go!

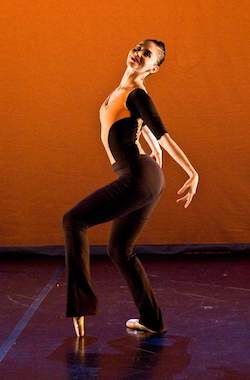

Photo by Rachel Neville Photography.

Pre-audition

Being courteous with dancers’ time and expectations indeed begins before the audition. Curet shares that she pre-screens dancers seeking to audition through a video requirement. She invites to live audition a certain number of dancers who catch her eye through their videos. This saves those dancers who don’t seem to be what Curet is looking for the time and effort of auditioning in person when there’s little to no chance that she’ll bring them into her company.

A secondary effect here is a less crowded audition room, less frustrating for the dancers and in which Curet can see more from each of them. Further, she holds public classes which dancers can attend, to see how the movement feels before committing the resources necessary to send in a video audition as a first step.

Hedberg favors this kind of transparent pre-screening as well. She recounts certain instances when she’s auditioned with slim to nil chance of getting the gig — not because of anything to do with her technical or performance skills but because of a physical characteristic or characteristics that she can’t change. “Sometimes I wish casting directors would state what they are looking for in particular,” Hedberg says. “If they are looking to hire someone super tall with brown hair, I’d know not to show up, and then they would get to see lots of dancers with the look they’re after. Everyone would win, and no one’s time would be wasted.”

Hedberg does acknowledge that every chance to put herself “out there, network and experience something new might very well still be worth it. Yet zero chance of landing that role — and there likely never will be a chance of landing that role — it comes to question whether auditioning is worth my time or not.” It’s a question of giving dancers enough information to put them in control of how they spend their time and energy, or not doing so.

Audition

Hedberg also remembers a particularly well-organized audition experience, that dignified and respected the dancers with the level of decorum and thoughtfulness that they themselves were bringing. All aspects — from their numbers, positions in the room, which studios they’d be in when and other details — were crystal-clear. Dancers could therefore fully focus on what they were being evaluated on — their technique and artistry — rather than be distracted by any confusion on details and logistics.

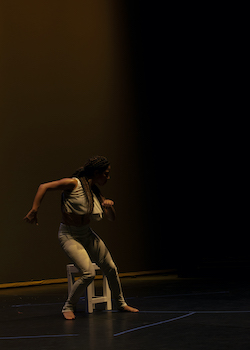

Photo by Danel Photography.

“I remember the audition feeling stress-free beyond the normal stresses of auditioning because it was so well organized,” Hedberg recounts. Directors can make an enormous difference for nervous auditioning dancers by lowering their stress, and allowing them to focus on what’s really important, through such clear organization.

Clarity around time commitment is another way in which directors running auditions can be courteous, or less than courteous, to auditioning dancers. For example, Curet runs her auditions in a workshop format, a few hours on a Saturday afternoon. That’s a good deal less than the six-hour or multi-day auditions some directors hold, and in which she can still see what she needs to see.

Also, recall, all dancers have been pre-screened through video auditions — so they know that they have some sort of shot at being hired. Yet none are cut before the afternoon is done — so even if they aren’t, they still get a great class and know to block out those hours on their schedule. Dancers are notoriously short on time, and directors can respect that (and over time, on a wider scale, help that) with clarity around audition time commitments.

Wider view: Acknowledging dancers’ humanity

Verduzco surfaces key broader matters relating to artists’ humanity, role in the world and how regarding both plays into the dance world’s internal operations, which includes auditions. She warns against perpetuating society’s view of dancers as just bodies to be used toward one’s own end — evident in the term “cattle call”, which “disgusts” her. The term undeniably carries a whiff of dehumanization. In contrast, fully respecting dancers, in all of the ways here discussed — and far more — acknowledges their full, complex humanity.

Photo by Daniel Olguin.

Verduzco cites a laundry of bad audition experiences — “having to pay to audition, being disrespected as an artist as well as a person, being the recipient of bad manners, power games and ego-based attitudes, being treated as a ‘child’ with no maturity to choose or decide, assuming that if we are there to audition we are willing to take any unfairness to have the possibility to dance and participate in an art form.” She also points to a larger picture, however, with these things as symptoms of bigger causes.

The lack of social regard and funding for the arts leaves everyone short on time, money, mental space and patience, for instance. That can lead to shortness in temperment, lack of clarity in logistics and expectations and treating each dancer just like one of a pack. Directors might be looking for a certain technical level or physical stereotype (“typecasting”), but Verduzco is clear that “none of these qualifications, by themselves only, give us value as artists and human beings. We are who we are at the core, regardless of our low, medium or high extensions, the technical proficiency that we work so hard to achieve, our different body types, performance experience or virtuosity.”

Verduzco points to our values and our unique personalities as far more important, and hopes that “directors and choreographers are not only in search for any kind of stereotype but also in search for dancers who can generate the beauty, emotion and can deliver on stage as artists what is needed to be expressed.” What can support that sort of wider, deeper and more comprehensive vision? As Verduzco puts it, “Being in an audition environment where who [dancers] are in body, mind and spirit is respected and valued.”

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.