Available through artistsclimatecollective.org.

August 31-September 28, 2021.

Artists naturally have a platform; they can speak through their work. Some use that platform to speak up on issues in the world that matter to them. Art’s sensory and visceral qualities can make an issue more vivid, more emotionally resonant, more human. That was all certainly the case with Artists Climate Collective’s dance film Art to Action. The organization “is dedicated to using the arts as a vessel to promote a positive impact in the fight against climate change.”

No matter one’s views on climate change, these artists’ commitment and authenticity were compelling and commendable. Hearing directly from artists also made their work all the more authentic and rich. Those things paired with thoughtful and skilled creative crafting of each work by each involved collaborator, the film was something any viewer could enjoy. And some, if inclined to listen to its message, might even be moved to action — “art to action.”

X Years kicked off the program, with choreographer Phillippe Jacques sharing the work’s concept — the youth of today not being able to always enjoy the natural world that’s currently present, and the emotions that come with that understanding. The short film began with dancers spread out in an open field, under a bright sun (film work and editing by Jordan Popowich). Their gaze was distant, looking far beyond themselves, and also resolute. They moved slowly and intently, as if mindful of every moving joint and contracting muscle.

As the score of ambient electronica (“Untitled” from Burial) rose in volume and its speed picked up, the movement evolved accordingly: more expansive, more accented, more technical. Yet the dancers remained centered in their presence, focus, and the natural space holding them. At a particularly poignant point, the dancers stood in a line and swung their arms in a circle in canon timing. This moment reminded me — vividly and into my bones — that the simplest movement can hold the most meaning.

That movement vocabulary developed into bigger, more forceful movement — which the dancers danced in their own timing, and in their own unique movement signatures. I thought about how in making change in any area of life, we must work together yet bring our unique talents and experiences to the work.

The score then shifted to something more mournful. The dancers again looked around to the natural space around them, taking in what isn’t guaranteed to last. The score rose again, and I sensed a new element of hope — reflected in the dancers’ expansive, soft yet assured movements. Coming in and out of unison, they found common purpose yet stood firm in their uniqueness.

Toward the end, the dancers joined in a movement almost blissful and playful, jumping side to side with arms raised toward the open sky. This choice once again reflected that hope, the need to find joy and the possibility ahead. The dancers’ white costumes reflected that possibility, as an open slate of what the future can be.

In a final ending section, they formed a circle and fell to the ground, shifting to turn a cheek to the earth, acknowledging its preciousness — bringing sadness to the moment. Despite that sadness, one dancer rose and gestured with conviction, and then gestured to the dancers in the circle as if calling them to rise. With courage and intention, we can call each other to action.

Later came Perspective — A Work in Progress, a story of connection and separation, of closeness and distance, through abstraction. Choreographer Leiland Charles introduced the work, sharing its concept of the effects of climate change on personal relationships. The film opened on a quintet of dancers in a brightly lit, white room. The blank slate quality of the white space brought the specifics within the work to a more universal space.

The costumes, of dark colors with different colored leotards, offered a sense of formal beauty — but also a relatability and everyday quality that could also allow any viewer to see themselves in the relationships portrayed. The contrast of the dark costumes and the white, brightly lit setting was also visually clear and appealing.

The dancers, from BalletMet (Columbus, OH), began moving in a circle and then branched off into separate groups. They found frequent interactions with other dancers and in new areas in space — bringing a frenetic quality. That quality reflected the uncertainty, social upheaval and uprootedness that scientists tell us are in our future if we fail to act on climate change.

The score (in motion by Gabriel Gaffney Smith) brought a mournful, mysterious quality to the movement — in a sense that the future is unknown, but it likely holds suffering. Yet the clear, focused gazes of the dancers offered a grounding force amidst the freneticism. The choreography was classical, lifted, highly codified, yet fresh gesture and shape made it fresh and innovative. It allowed these performers to shine in their own individual movement qualities.

Toward the end, the dancers stood in a line and moved in canon with simple, clear movement. This felt to me like a reflection of the common purpose needed for mass social action and to make change. Enhancing this effect, the dancers gazed intently to the camera, in effect to the audience, as the credits rolled. It was as if they were asking viewers what their action will be.

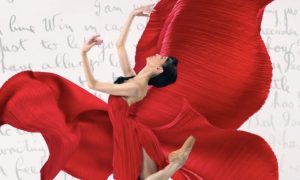

Reverie was a breath of fresh air and a reminder that amidst multiple ongoing crises, beauty still exists in this world. A dancer (American Ballet Theatre’s Anabel Katsnelson) moved in a lushly green and open space, barefoot and in a loose white dress. She moved in a way that was lifted but grounded, released but stable and supported. In the air was an Isadora Duncan feeling of moving in accordance with the truths of her body and those of nature.

The work began and ended with Katsnelson resting in the grass with her hands as pillows, hence “reverie”. This choice made me think of resting in a park on a perfectly temperate, cloudless day and it feeling like everything is at peace. Aligned with that same harmonious feeling, throughout the film a cellist in the center of the space (Sophia Bacelar) accompanied the dancer with an uplifting classical score (J.S. Bach Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major — Prelude).

The score was an undeniably beautiful piece of music that can resonate through the ages, and its timelessness led me to reflect on the past and the future; the sense of hope in the work could be hope for a better future, and black and white filter (film work and editing by Alana Campbell) could offer reverence for the past.

I also thought about how in a dream, one’s sense of time can be diffuse and hazy. Even with the urgency of social and environmental crises we face, and the resulting need to act fast, we can’t forget to take certain moments to let our sense of time be dreamy — to leave that urgency behind and dance in nature, to appreciate the beauty in life that we’re fighting to preserve.

Darian Kane’s All Eyes Forward closed the show, a work of both memorable concept and execution. In her introduction, Kane explained the very unique and bold concept of nature and industry personified, and those forces debating rights and ownership to this earth and its wonders. The movement was thoughtful, beautifully balanced between codification and ingenuity, and remarkably executed by the performers.

The score (Cc by Gabriel Gaffney Smith) was full of tension and freneticism, effectively supporting the atmosphere of contention at hand and the concept behind it. The setting, an industrial park with buildings dressed in graffiti and a perhaps once grassy area now full of dirt and concrete, further enhanced that atmosphere.

Earth tone costumes visually split the dancers into male and female groups. Thinking back on the concept of nature and industry personified and in tension, was nature female here? All historical and philosophical context considered, that was intriguing to ponder.

Indeed, various pairings put nature and industry head-to-head. On a smaller scale in a real-world sense, these are tensions between one company and individual forest area, bodies of water, or Indigenous tribes who call upon those resources for livelihood and spiritual lifeblood. An especially poignant moment featured one dancer being lifted and then running in place while carried — illustrating undesired effects of industry and lack of consent from those affected.

The ending section had all six dancers mostly moving in unison, embodying the totality of those individual tensions and debates. In a way, that’s similar to art on larger issues in the world — a specific window into an issue with the potential to speak to something much bigger and much more universal. It’s artists leading the way in that process by crafting the window, fueled by their convictions and commitment.

Those essential ingredients, along with thoughtfulness and intentionality, are what make works like Art to Action wonderful — wonderful on many levels, from something to simply enjoy to something that can change the course of the way someone engages with an issue. With the latter multiplied many times, that could just change the course of history. That’s art to action.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.