Part One

Life has its seasons — shifting practicalities and needs leading us in different directions. Dance is a pursuit calling for sincere dedication, for hours in the studio full of mental, physical and spiritual investment. Yet, there are times when life guides us elsewhere, and we place that dedication elsewhere. Once a dancer, always a dancer, however; those hours and energy spent become part of who we are.

Accordingly, sometimes we find ourselves back in the studio, back doing pliés and counting off “5678!” What’s it like to come back to dance after time away — physically, mentally, creatively and otherwise? What’s challenging, and what unexpected gifts can emerge? To learn more here, Dance Informa spoke with four dance artists who came back to dance after time away from it — two of their stories shared here and two more shared in Part II of this series (stay tuned!).

Alexandria Nunweiler: Dance is the answer

Alexandria Nunweiler’s mom is a dance educator and studio owner, so growing up dancing was a rather natural outcome for her. She attended College of Charleston before transferring to Winthrop University, where she majored in dance and professional writing. After graduating, she was a full-time dancer and teaching artist in Charlotte, NC. That came with a whole lot of travel and “hustle”, leading to burnout. The lifestyle felt financially unsustainable as well. Craving change, she decided to head back to school for business in Boston, MA.

After graduating, she held a corporate job in Boston for two years. Technically, she could still dance, but what ended up happening was “taking class sporadically and presenting work here and there,” she explains. “I gave into pressure to take a more traditional path.” Ultimately, Nunweiler realized that such a path wasn’t the right one for her. “What am I doing, and why am I miserable?” she would ask herself. She realized that dance was her answer.

COVID was really the thing that made that dynamic crystal clear for her, crystal clear enough to take action for change in her career and in her life. “The pandemic spurred reflection for me, and I also couldn’t distract myself with fun things and ‘breathers,’” she recounts. “I fully realized that what I was doing wasn’t fulfilling.”

Shifting course to being a full-time dance teaching artist again wasn’t easy, particularly in the midst of a pandemic. Yet, Nunweiler found tools to help with that, including massage therapy and a yoga teacher training (for building strength and stamina back up as well as mental and physical self-care). Her mom is also a mentor to her, she notes (which demonstrates the importance of calling upon social networks for help with big career and life shifts).

The result of coming back to dance full-time for Nunweiler? “I’ve noticed a big, big difference in my mood and a feeling of fulfillment, which my partner has even noticed!” she shares with a little laugh. She’s been able to build her own schedule — and even cut back on teaching a bit and focus more on creative projects, particularly in the summer when teaching artist work naturally slows down.

One of those projects is 10 recalling 20, which will include film, COVID-safe in-person, workshop, and writing components. The project will highlight, through dance and storytelling, 10 different individual’s experiences of living through 2020 — 10 people from all walks of life. “I feel like I’m living and working more on my own terms now,” Nunweiler says joyfully.

Along with skills like acceptance from yoga, she affirms that “it’s all relative; it’s not about status or comparing ourselves to each other or competing.” She believes that what matters is finding fulfillment in touching people’s lives in big or little ways. For her, that’s through sharing the art of dance, which is “elemental to humans,” she argues. “There are so many ways to have a life in dance, and the body and soul can start to shut down when you’re not dancing but still you need it.” Nunweiler has found that she can’t just let that shutting down happen; dance is a much better answer, and it’s her answer.

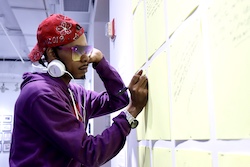

David “Sincere” Aiken: Find and share what’s you

American Ballet Theatre came to PS156 (Queens, NY), and they picked one young David “Sincere” Aiken to help demonstrate the dance lesson. He had already been involved with singing and acting, so he gravitated toward dance fairly naturally. He didn’t love aspects of ballet, such as having to wear tights — but after seeing a Michael Jackson-themed routine, he knew that he wanted to dance. Aiken had “two left feet” at first, he recounts with a laugh, yet he trained in a wide variety of styles and kept at it. After a couple of years, his technique was more refined and he was able to pick up choreography much more efficiently.

The studio where Aiken was dancing asked him if he could teach hip hop, and from there, he delved deeper into the style. With choreography and performance gigs under his belt, he got a scholarship to dance at Long Island University. Yet, while in school, he got an opportunity to tour with the R&B singer Ashanti, as a dancer, and made the hard choice to leave school in order to take the opportunity. That led him working as a dancer and choreographer in Los Angeles, and that’s when he saw things in the dance world that bothered and discouraged him.

Through spaces like social media, auditions and rehearsals, he didn’t see a true valuing of talent, hard work and dedicated years of training. With dance television shows like America’s Best Dance Crew and So You Think You Can Dance, the dance industry also felt oversaturated to him, he shares. At the same time, Aiken wanted to be fully committed to dance and aim for excellence if he was going to do it all. “I didn’t want to just ‘play around’ with dance and movement,” he explains.

All of those factors at play, Aiken decided to dive back into music rather than spend time and energy on dance. Yet, he “didn’t realize how much I needed dance until I didn’t have it. I needed [a dance community] around me,” he shares. Aiken describes having low energy and “missing an outlet that I would normally use to release my emotions” when not dancing. “Beyond missing dance, I realized how much I needed dance to live. Dance brings joy to my life….medicine to my drama.”

The Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020 rose up, and it became the thing that ultimately led him to dance again. Aiken was moved to use his art to speak out on social justice. He choreographed a solo to an original racial justice-themed song, had someone shoot it and then put it up on YouTube. That YouTube clip got a good deal of visibility, leading to booking requests and him setting the choreography on a larger group of dancers. Artists have been wanting to have content ready to release once COVID feels more under control, he adds, leading to more performing and choreography gigs. “It was sort of an organic return to dance,” he says.

Physically, “coming back to dance was rough for the first couple of weeks…from getting Charlie horses in my legs and my body feeling like a truck hit it the next morning,” Aiken explains. That “quickly reminded me to stretch again,” he notes. Getting stamina back, on the other hand, “was like riding a bike” — because he had always been a dancer with a lot of energy.

These opportunities have continued, including being a choreographer and creative director for Lil Mama’s “UHOH” music video. He also wants to make a visual album with his own choreography and music. He hopes to inspire dancers to “really make something of their own and put a lot into it,” he shares. “If you see something missing, make it yourself!” As for social media, Aiken says he’s found a “niche” within it as well as an appreciation for what’s useful about it, such as networking and brand building.

“I had to go back and realize why I dance — not for the clout, but because I love it,” Aiken affirms. “It’s not about the likes. I don’t want to follow the trend; I want to create.” The communities that dance creates — the energy and conversations that emerge in the studio, on stage, on set — are also incredibly meaningful to him. “There’s no substitute for being together in space [in that way],” he argues.

Aiken believes that he’s with dance for good now. “When a lesson is given to me, I learn my lesson. I think the lesson has been given to me; I know that I need dance.” He also believes that he has a lot to share and contribute — his perspective of the importance of hard work, as well as going back to fundamentals and honoring dance history, for example.

“Do your research,” Aiken advises. “It’ll make you a better dancer. You can do it right and then make something of your own.”

Aiken and Nunweiler’s experiences show that sometimes it takes stepping away to know what that something of your own might be, and the degree to which you just need to make it. After all, as A Chorus Line tells us, “a dancer dances.”

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.