Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, NY.

June 8, 2022.

In Akram Khan’s version of the classical story ballet for English National Ballet, rather than being a peasant, “Giselle is one of a community of migrant garment factory workers (the Outcasts),” according to the program notes. The noblemen have been replaced by Landlords who see the factory workers “as little more than exotic entertainment” and are content to ignore the Outcasts’ needs to promote their own personal gain.

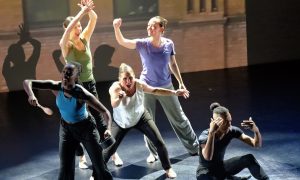

The curtain rises on the backs of a crowd of people pushing their hands against a large wall. As they step away, handprints are left behind on its surface. A lively dance ensues, but is soon interrupted by rising animosity between Hilarion, Giselle’s “would-be lover” who “trades and mimics the Landlords for his own and his community’s profit,” and Albrecht, a Landlord who has disguised himself as an Outcast to woo Giselle. The music stops abruptly as the Outcasts form two, single file parallel lines, with Albrecht caught between them; he lifts the leaning torsos of several Outcasts, presumably looking for Giselle amongst the crowd to no avail. The music soon builds again, and is complemented by the distinct 1-2-3 rhythm of the dancers’ feet as they charge across the space with animalistic chassés.

Upon being reunited, Giselle and Albrecht perform a romantic duet, at first tentative but increasingly playful and free. A series of sirens stops them short and the wall slowly rotates back, revealing the Landlords in all their costumed splendor. They move forward, unhurried and the wall returns to its place. Albrecht is offered a symbolic black hat. Giselle is mockingly offered a black silk glove; as she reaches out to grab it, the Landlord drops it to the floor. Albrecht tries to make Giselle bow, but she refuses. The other Outcasts bow without much chiding, but Giselle wants no part of it. The Outcasts then perform a staccato petit allegro characterized by high passés and syncopated rhythms, attempting to impress the Landlords with their skill. Soon, Giselle is encircled by the other Outcasts; the group that surrounds her becomes a single oppressive organism and dancers stampede across the stage in a frenzy. When the wall begins to rotate again, the Landlords disappear behind it, taking Albrecht with them. It rotates faster and faster, and Giselle is left alone to die as the curtain falls.

At the start of Act II, the curtain rises to reveal the Landlords scattered across the space with the wall hovering horizontally above. One sits atop it with Hilarion while Albrecht dances below, swaying, pounding the floor, and addressing the other Landlords aggressively amidst virtuosic turns and jumps. Soon Myrtha, Queen of the Willis (ghosts of factory workers who seek revenge) enters from beneath the wall, dragging Giselle along with her in a feat of powerful bourrées, marking the first appearance of pointe shoes which permeate the second act. She carries a stick which she uses to manipulate Giselle, eventually placing it in Giselle’s mouth. Giselle bourrées from side to side like a drunken tightrope walker as she clutches the stick between her teeth.

Then, an ominous line of women enters donning identical brown dresses; each wears her hair down and carries a stick in one hand, the other flexed at the wrist. They move like warriors, rarely coming down off the boxes of their pointe shoes, their sticks shifting to form intricate geometries. When Hilarion enters, he and Giselle perform a compelling series of lifts, but the Willis are in charge here. They bang their sticks on the floor rhythmically, eventually trapping Hilarion in their snare.

When Albrecht arrives, the Queen threatens him. She gives Giselle her stick and with it the power to harm Albrecht. Instead, Giselle and Albrecht dance together again. (At one point, the beautiful Tamara Rojo, who is also the artistic director of the English National Ballet, holds an incredible sous-sus, not a bourrée in sight, and at age 48 no less!) The music feels almost muted in comparison to all that came before and the couple completes a series of seamless lifts, one of which begins with Giselle standing on Albrecht’s stomach and somehow ends with her soaring in the air above him. But the Queen has had enough; she separates them with her stick and leads Giselle back beneath the wall, which returns to its original position, handprints facing the audience. Albrecht pushes the wall frantically (although not quite believably), and the wall draws back from his push. At first its motion seems like an illusion, like looking out a parked car window as another car rushes by. The curtain falls.

The piece is ideologically admirable, providing an X-ray of global class politics with a dint of ambiguity that rescues it from mere preaching. While the class allegory may be hampered by its reliance on outdated royalistic imagery, the stark lines of demarcation, power dynamics, and mechanisms of exploitation are very much in evidence today. Hilarion’s character is of particular interest. According to the program notes, he is a mediator between the world of capital and the world of the expropriated. He purportedly acts for the benefit of the Outcasts, yet his domineering nature and tendency to compel conformity rather than resistance leaves a bad taste in the viewer’s mouth. He seems to be midway between an “Uncle Tom” figure (a sellout puppet for the oppressors) and a trade union leader. This ambiguity begs the question: does Hilarion deserve the Willis’ wrath more than Albrecht? Perhaps their final decision to annihilate him lies precisely in his lukewarm, centrist status, his conciliatory bent that holds the Outcasts back despite nominally acting in their interest.

Although the work is unquestionably epic and well constructed, I found myself wanting for more lighting and musical variations. It was difficult to make out even the lead dancers’ faces for most of the piece, which robbed the work of certain dramatic possibilities. I was also unconvinced by the piece’s apparently contemporary angle. How are the Landlords different from the noblemen they set out to replace? By the same token, how are the Outcasts truly differentiated from their peasant ancestors? While the costumes were stunning, they blocked the viewer from truly believing that the narrative was taking place in the 21st century. Furthermore, while the movement vocabulary had a contemporary flare, I wanted it to push the envelope even further without ditching its classical roots. From many of the main characters, I believed their technique but not their passion. I wanted to see the struggles of these characters pushed to their physical limits, for Albrecht and Hilarion to fall off their centers in a fight for their lives, for Giselle to reach beyond her flawless lines into the unknown territory of an unknown future that we all must grapple with.

By Charly Santagado of Dance Informa.