Dance Informa had the opportunity to speak with NYC dance veteran Felice Lesser about her unique career as a multidisciplinary dance artist. From choreography to directing, from animation to cross-disciplinary collaboration, Lesser offers us a wealth of information about her career and what dance means to her.

How did you get started in dance? What is your background, and how has it led you to become the artist you are today?

“My early ballet training was with Russel Fratto, Jeannette Lauret, Charles Nicoll, and James Zynda, and with Alexandra (Sandy) Broyard for modern dance, at the Academy of Ballet Etudes Repertory Company in Norwalk, CT. The single most important thing I took from all of these teachers was their deep and abiding love for and dedication to the art form. And with Mme. Lauret’s vast knowledge of ballet repertoire (as a former member of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and American Ballet Theatre), we were given a firm foundation in ballet choreography.

Though I knew I wanted to be a dancer from the time I was six years old, I incurred a serious injury at age 11 when I tripped over my dog and fractured my ankle in three places, which for all intents and purposes ended my ballet career before it ever began. Misdiagnosed as a ‘torn ligament,’ I left the doctor’s office with an ace bandage and a cane, and danced in a considerable amount of pain from then on. Those were the days when you were instructed to ‘work through the pain,’ so I did. There were always things I couldn’t do as a result – like fouetté turns. The extent of the injury wasn’t discovered until I was 19 when (after having fractured a sesamoid bone in my other foot dancing on a concrete floor) both feet were x-rayed for comparison, and my feeling that something had been terribly wrong all along was finally vindicated. Unfortunately, it was too late to do anything about it. But I never stopped dancing. Nothing was going to keep me from dancing.

The summer after graduating from high school, I attended the American Dance Festival (ADF), where I was one of a group of dancers chosen to perform with Lucas Hoving’s company in his Assemblage (with Pina Bausch as the soloist). One of the other dancers chosen was Thomas Holt who was on his way to New York to start a company of his own. Tom and I became good friends and dance partners, and a few years later he played a crucial role in the founding of my own company.

College was expected in my family, so following the summer at ADF, I went to Barnard, majored in music (Barnard didn’t yet have a dance major), fulfilled my gym requirement with ballet classes at Joffrey and modern dance at the Graham School, and accelerated so I could graduate in three years. The plan was to then attempt to make up for lost time and pursue the career I really wanted – that of a dancer. (In those days, you generally either danced professionally or went to college. Not both.) Choreographing dances for student concerts at Barnard and Columbia, often to original scores by Richard Einhorn, another music major, gave me an opportunity to perform. In my senior year, choreographer/dancer Pearl Lang attended a post-performance party and said to me, ‘That was the best piece of student choreography I’ve seen in years!’ My boyfriend said later, ‘You really should seriously consider what she said.’ So, while my desire was simply to dance, in the back of my mind the idea of becoming a choreographer took root.

One of the departmental requirements for graduation was a senior piano recital, but my advisor, Dr. Patricia Carpenter, knew about my dance background and asked if I would like to produce a dance performance instead. I jumped at the opportunity and that’s how it all began, with her initiating me into what I’d face as a choreographer/director later on – finding space and personnel, choreographing and performing, doing the administrative work – all the things that would consume my life going forward. I learned then that whatever you could do yourself for free, you did, and then you either learned how to do the things you couldn’t do or found people who could do them for you – for free or through a barter arrangement.

Seeing my senior recital led Joe Spivack, a graduate student, to ask me to choreograph one of his works, which was to be performed at the Horace Mann Theater. The night of the performance, Tobias Picker and Charles Wuorinen happened to be in the audience. Toby was starting a group of his own, The Troupe for Contemporary Music and Dance, and asked me to be a part of it as the choreographer for Charles’s Arabia Felix for the premiere performance. And composer Nicolas Roussakis, who had also attended my senior recital, asked me to choreograph his Six Short Pieces for Two Flutes for a performance by The Group for Contemporary Music.”

When did you start Felice Lesser Dance Theater, and how did you decide that starting a company was the right move for you? Can you say more about your “one-woman operation” and all the work that goes into running the company?

“In late 1974, Tom Holt came to me with a proposition. He wanted his company to perform at the American Theater Laboratory in June 1975, and needed another choreographer with whom to share the concert and expenses. He asked me, and I said yes. The catch was that you needed to be a 501(c)(3) organization to perform at that theater, so I had to form a nonprofit organization right then and there, and that was how my company was born. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

Had I known what the next 47 years were going to bring, I would have never started my own company at that point, but at the time, Tom’s offer was the one and only door that opened up for me and I decided to walk through it. I saw forming my own company as a performing opportunity for my friends and I, which felt like a worthy cause; all we wanted to do was dance. We were young and full of hopes and dreams, and took a gamble that we’d magically be discovered, that an organization would suddenly spring up under our feet. But it didn’t happen that way. I soon learned that when you’re an ‘outsider’ and haven’t come from one of the major companies as a dancer first, you’re seen as suspect from the very beginning and largely ignored. Written off for what feels like forever. You don’t get the grants or performance opportunities. People don’t come to your concerts because you’re not a ‘name.’ (And being that I was 21 when I founded the company, what did I really have to say at that point? I could have used some time to mature first.)

When you’re a one-woman operation, the work that goes into running a company is staggering. You’re single-handedly responsible for the work of about 20 people (usually unpaid since every cent that comes in, you’re saving up to pay your dancers or performance expenses). Today, for example, in prepping for my new work, Trap Ist, I’ll tackle the first step in our audition process: sorting through and watching online reels from dancers and listening to demo tapes from voice over artists (so far there are 126 to go through). Then I’ll read through notes from our lawyer regarding the theater contract, execute Lorne Svarc’s Interactive Technology contract, make inquiries on taking out a Special Events insurance policy, find and book space for a dance audition, and see if I can get Quickbooks to function. (It was misbehaving yesterday, just when the accountant needed it to get started on our 990.) Then I’ve got to finish up two proposals for dance residencies that I’ve applied for in previous years and haven’t gotten. (But as the New York Lottery says, ‘You’ve got to be in it to win it!’) Hopefully, Jonathan Burkhardt, the artist for my upcoming work, Trap Ist, will stop by later to help set up the new computer we’ll be using, and will start teaching me the basics of Adobe Premiere, which he uses (I used Final Cut Pro previously) so I can begin compiling the music with video I’ve already shot. To close out the day, I’ll have a Zoom meeting with one of the applicants for Trap Ist to listen to her read for one of the roles.”

How did you get involved with video and animation, and how have these mediums informed your work?

“I was always interested in including other art forms in my work – music, art, theater – and did so from the early days of the company when the composers I knew wrote original scores, and artist Janet Braun-Reinitz created large-scale paintings or hung draped, sculptural material ‘environments’ on the stage within which we could dance. I always felt that dance was far more interesting when coupled with other art forms.

By the late 1970s, I could see that computer dance would be part of the future of the art form, and I really wanted to be a part of it when it arrived. Walter Sorell’s quote hammered in my mind: ‘The greatest artists of all times are able to reach us across many centuries only because – whatever their theme has been – they created it out of the spirit of their own time.’ And the writing on the wall said the spirit of our time was going to be technology. I imagined all the things that could be done. Gravity would no longer be a limitation. I’d have all the dancers I’d ever want. And choreography could go far beyond what the human body was capable of doing.

I changed the name of my company to DANCE 2000 (I obviously hadn’t given any thought to what was going to happen once we crossed the millennium as it seemed so far away at the time) and enrolled in a computer course at the New School (where I taught dance) to see if I could pick up the skills I’d need to bring my tech visions to life. I quickly saw that I was completely out of my league. You needed an aptitude for math — never my strong suit. Fortram? COBOL? Just the mention of computer languages made my eyes glaze over. So, while I hoped to eventually participate in some way, I left it to those who were infinitely more qualified than I to develop computer choreography.

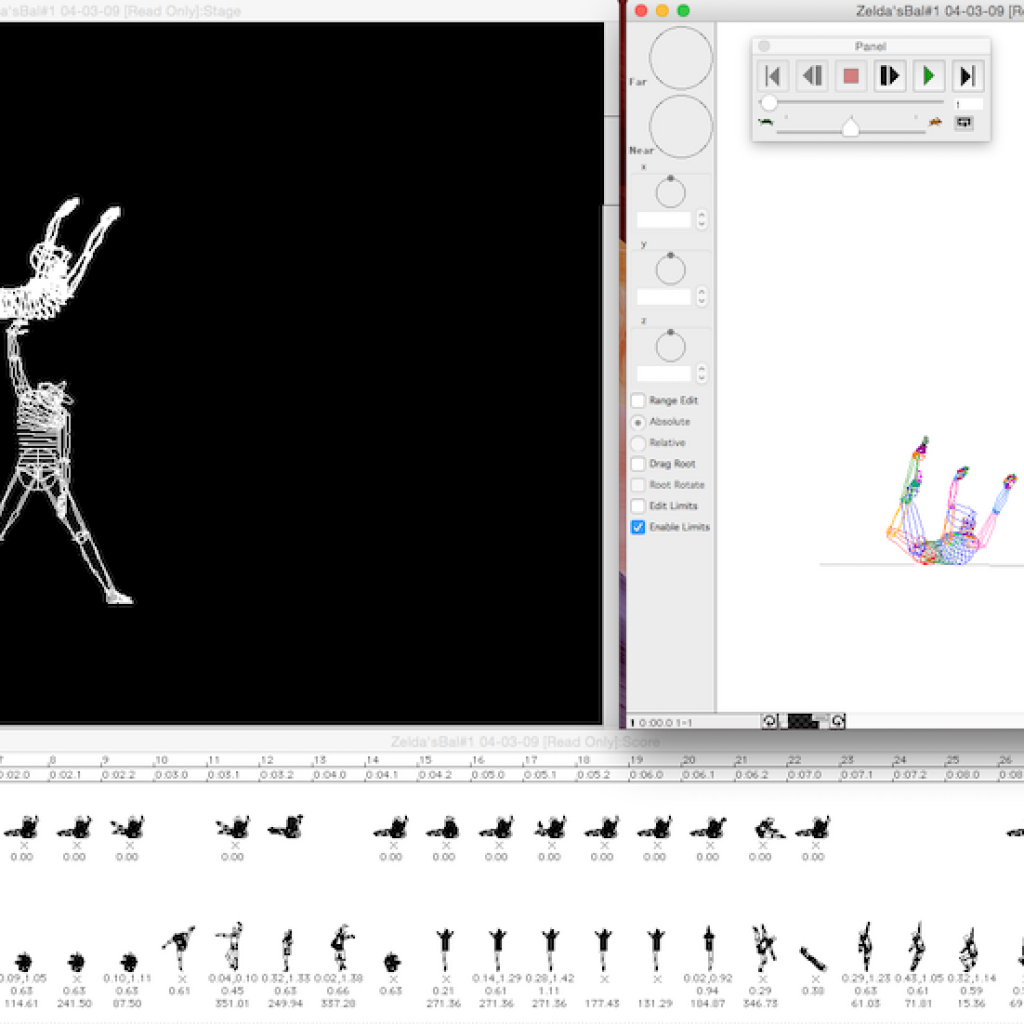

Eventually, I came across an article in Science Magazine and saw that Thomas Calvert of Simon Fraser University in Canada had created LifeForms (subsequently renamed Dance Forms), a dance animation software program. Still wanting desperately to be a part of this coming revolution, I rushed off to attend a national conference on Computer Dance where one of his associates, Thecla Schiphorst, was speaking. Approaching her after her presentation and pleading my case, she very generously gave me a copy of LifeForms. I bought my first computer, a Mac Centris 660 a/v, and had my cousin Andy, a computer engineer, teach me the basics. Over the years, Dr. Calvert and his team were extremely generous in allowing me to use LifeForms for my own work, and furnished the software for my Arts-in-Education residencies in Idaho and elsewhere. As for my work with video, that came later, in 1998, when the Field offered a free program in conjunction with Manhattan Neighborhood Network for artists working in various mediums to learn how to film and edit video. That program changed my life. After I had completed it (and then went on to take other television and video courses offered at MNN), I had the tools to do what I had set out to accomplish.”

I have always been curious about the LifeForms software. Can you tell us more about it and how you have used it during your artistic journey?

“LifeForms (renamed Dance Forms) is fun and relatively easy to use, and the great thing about it is that if you’re a dancer, you already know how to design the movement. You‘re given a wireframe body, and you can move its limbs into various positions. The body can be put on a ‘stage’ and moved from place to place. The poses you’ve drawn can be connected one to another so you can construct actual dance phrases either manually or by letting the software make the connections. The best part is being able to do things no human being can do – defy gravity, turn forever, jump through the roof. I’ve even used it to make costumes by squishing up some of the dancers into little balls and then layering the balls onto another dancer to form a dress or tutu. And those tutu dancers can then be unfolded as the piece progresses so that they return to the shape of a dancer’s body and can dance from there.

The one drawback is that it’s a little cumbersome to actually notate choreography. I tried it once or twice, and even did the entire opening section of The Green Table for practice and my own amusement. But for augmenting live dance work with visual design, it’s great, and the software has helped me through various ‘creative emergencies.’ When I was working on my spy spoof, Funding the Arts (2010, Baryshnikov Arts Center), I needed cartoon characters to supplement the live dancers. I contacted two well-known animators and was told, ‘This kind of animation will cost you $5,000… per minute.’ With a 90-minute piece… Well, you do the math. My friend (the composer), Seymour Barab, said, ‘Felice, why don’t you just go ahead and do it yourself?’ So with LifeForms (and an assist from Motion and Anime Pro), it all got done.”

Can you tell us about your ‘living movies’? What does that distinction mean to you?

“I was basically looking for a way that an independent choreographer could create the equivalent of a Broadway show on a ‘nonprofit sized’ budget. When you’re running your own company, you’re always looking for savvy ways to get the wild ideas in your head to co-exist with the realities of no staff, no space and very little financial support. In response to my big ideas and limited resources, I started making what I called ‘living movies’ (multimedia works with live dance, theater and a projected “moving set” of animated video) in the 1990s. Owing a nod to the old Gene Kelly films in which he appeared to be dancing with cartoon characters, I wanted to do something similar, but rather than putting everything on film, I’d project video onto screens behind my dancers for them to interact with.

The other thing that came into play was that out of the blue, I had started writing plays and screenplays. Writing was something I could do by myself when I didn’t have the money to hire dancers or pay for rehearsal space. My first play, Running Backwards on the Treadmill (performed at Symphony Space in 1995) revolved around a choreographer’s struggles to mount a performance against almost insurmountable odds (as they say – write about what you know). It became my first ‘living movie.’ In it, I used projected LifeForms animations for the first time to depict the ‘voices” in the choreographer’s mind.

‘Living movies’ enabled me to bring set design and special effects into the work for only the cost of my own (free) labor. And when the world switched from analog to digital, I learned Final Cut Studio which gave me a timeline into which everything could be laid out (music, dialogue, animation).

Unfortunately, technology keeps advancing much faster than I can keep up with it, and it has reached the point that unless I want to spend the rest of my life upgrading expensive equipment every year and learning to use very sophisticated creative tools, I need to find people already well-versed in and working with up-to-the-minute technology, such as the artists I’m collaborating with now. The worst part for me about these technological advances is that the tools I was very comfortable using have become obsolete, and I’ve lost access to many of them and their unique modes of expression.”

Can you talk about your new piece, Trap Ist? What are you most excited about in relation to the piece?

“Trap Ist’s story focuses on contemporary topics: the destruction of the environment, controlling our A.I. before it is too late, racism, diversity and inclusivity, unwelcome immigrants in a strange land (or in this case, planet), and ageism. It references events from the history of slavery in the United States such as ‘Dancing the Slaves’ (when Africans en route to America in slave ships were brutally forced to dance so they’d stay healthy and command higher prices), and the Stono Slave Insurrection of 1739.

Here’s a brief synopsis: One second before the earth is destroyed in a nuclear holocaust, an egomaniacal, rogue A.I., transports a group of dancers (and the audience) to the seemingly uninhabited Trappist 1-e as its slaves in developing the planet. By mistake, A.I. also beams up Astana, an older female choreographer. Discovering the error, A.I. (about to murder Astana for spare body parts) is stopped by a seeming ‘power failure’ that temporarily saves Astana’s life. Waiting, she watches as A.I. ‘dances his slaves.’ Inspired by the dancers’ movements – and with a telepathic assist from the planet’s purely spiritual, technologically advanced life-form – Astana becomes a modern-day Joan of Arc. With a young breakdancer and what appears to be a leaf as her muses and champions, she leads a balletic battle for freedom that outwits and destroys A.I. But once the humans have triumphed, they are confronted by the planet’s own native life form who will not allow them to stay…

Trap Ist is similar to my previous works in that it’s a ‘living movie’ with a full-length script, original choreography and video, but it’s different in that I wrote Trap Ist with the goal of bringing audiences into the action from the moment they entered the theater; they, too, are ‘beamed up’ as enslaved humans, thus making the audience part of the cast. At times, through interactive technology, they’ll also contribute to the work. The dancers themselves will be representative of the diversity of our world, and to that end, I’ll attempt to combine very different dance idioms simultaneously in some sections of the choreography. The work takes place on a distant planet with a dwarf sun and other nearby planets shooting by so there will be lots of animation in the set design. I’m also going to try to choreograph a pas de deux for a live dancer and an animated leaf, which should be an interesting challenge.

Trap Ist will have music by a number of different composers: Borut Krzisnik, Stefania deKenessey, Richard Einhorn and probably a few more. Jonathan Burkhardt will design the animated set and characters using Lorne Svarc’s interactive tools, allowing him to create some rather magical special effects and enabling the audience to participate in the action from time to time. And in addition to the script, choreography and direction, I’ll also contribute some of the video.

What am I most excited about? I don’t think I’d use the word ‘excited.’ I think ‘petrified’ is more apt. It’s a huge production with a large cast, all kinds of technical complications and not a lot of time to put it all together. Will the interactive technology work? And what will happen if it doesn’t? Will I be able to find enough really good dancers who can also act? Being that the rehearsals and performances will take place smack dab in the middle of Nutcracker season, will I be able to find the ballet dancers I need? Is there a spectacular breakdancer out there somewhere who will want to work with a small contemporary ballet/modern company, not to mention a leading actress in her 70s who dances? And the biggest unknown is Covid lurking in the background. What will happen if our dancers get sick? Will we even get an audience if people don’t feel safe enough to come out to the theater? Will we have to shut down entirely if a new Covid strain appears? And how am I, currently hobbling around with two torn menisci, going to navigate the process? Those are the things on my mind at 4am when I’m jolted awake in a panic!”

What have been the most meaningful shows/performances of your career, and why?

“I’ve had many meaningful performances, and being invited as one of 20 choreographers worldwide to the 1991 International Choreography Competition in Tokyo was certainly a highlight. Another was having the chance to choreograph for the wonderful dancers of the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre when I was in the Carlisle Project. A third was performing for an audience of over 2,500 people at Lincoln Center Out-of-Doors in 1985. Filming the video for New York, NY (Joyce SoHo, 2000) with the extraordinary dancer Stephanie Lyon (now Albanese) also stands out. The two of us spent a full year running around town with a video camera, having incredible artistic adventures in parks, on the subway, on city streets, and especially at Project FIND where the seniors there became part of our moving set, creating a generational juxtaposition with Stephanie who danced in front of them on stage.

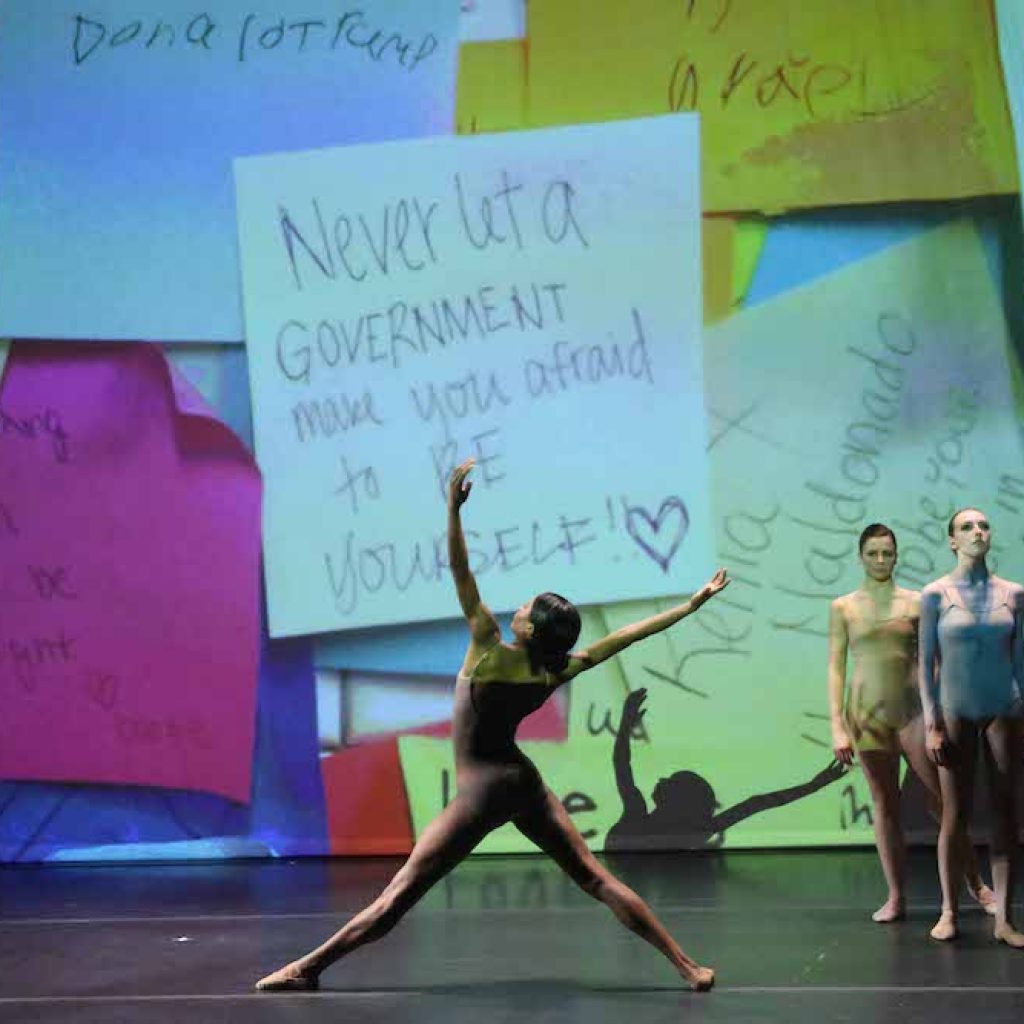

In a very different way, 2017’s Lightning also falls into the ‘most meaningful’ category. Premiered at The Duke on 42nd Street a few weeks after Trump took office, it dealt with important social issues confronting us at that time: racism, global warming, homophobia, xenophobia, and immigration. Strangers came backstage afterwards to tell me how much the work meant to them in terms of what was happening here in the United States. One woman confessed that she, an immigrant, no longer felt safe in America, and was frightened of what was to come for her and her family; another said that seeing the work was the first time since the election that he felt any hope at all. Our post-performance ‘talk-backs’ turned into profound conversations, giving people a chance to express their thoughts and vent about what was happening to our country.

Another piece that comes to mind is a very early one, Arabia Felix (1977). I remember a few days before the performance, my mother and I were seeing Aida at the Metropolitan Opera, but my thoughts wandered elsewhere; I couldn’t stop thinking about my piece. It was either going to be a big success or a tremendous flop. We had rehearsed the complex score in a small room at the Manhattan School of Music. The musicians and their instruments – including a piano and vibraphone – took up most of the available space so the dancers were very limited in how much we could move. Therefore, I choreographed the piece as a light comedy, allowing us to be additional ‘instruments’ in the ensemble, sitting or dancing on chairs, circling around the group on the perimeter of the room, mixing with the musicians, or popping up from behind the piano. When performance night came, there was laughter in all the right places and quite a bit of applause, and the next thing I remember was riding home on the subway, reveling in how lucky I was to be doing what I do. Adding a little icing to the cake was a phone call from Dick Einhorn the morning that Amanda Smith’s review appeared in Dance Magazine. He said, ‘If I were you, I’d go out and buy 10 copies.’

But if I had to pick just one performance, I AM A DANCER is probably the piece I’m proudest of. It was a ‘live documentary’ about freelance dancers trying to make it in New York – call it a love letter to all the dancers who spend their lives doing what they do with very little chance of acknowledgement or fame, other than their own satisfaction at doing what they love. The early creative work for me was the best part. The Field held lotteries for three-month-long residencies at their FAR space, and I was fortunate enough to get one. I hired two extraordinary dancers, Kristin Licata and Lauren Toole, videotaped them, and manipulated the footage so they appeared to dance with their own ‘clones,’ upside down, or with various special effects. The studio’s resident dog and cat made ‘guest appearances’ at critical moments, the dog chasing Lauren as she ran across the room or the cat doing a very similar warm up to the one Kristin was doing on the floor.

Performed at Baryshnikov Arts Center in 2006, with an expanded cast, the live dances were interspersed with filmed interviews so that the audience was brought directly into the lives of the people dancing right in front of them as they discussed issues like injuries, body image, financial insecurity, multiple jobs completely unrelated to dance and the very short career of a dancer – all coupled with the love for the art that kept them going in the field. Virginia Johnson (now director of Dance Theatre of Harlem), who I had never met, was in the audience and after the performance, she came over to me, introduced herself, and said, ‘You did everything right.’ In a field where there is so little, if any, positive reinforcement, I’ll never forget her words.”

What are your goals as a professor/teacher? What knowledge do you want to pass on?

“What I want to pass on is my love for this art – to get others to feel the same passion for dance that I do. My goals are different for the different populations I teach. When I present residencies in the states where I am on Arts-in-Education rosters (currently Nevada, formerly Idaho), I often deal with entire communities that have little, if any, exposure to dance. I construct residencies that introduce the participants to dance in a non-threatening way, often starting with folk dances as they consist of steps people have done all their lives: walks, runs, hops, skips, stamps, jumps. And once they’ve gotten over their initial fears, I can move into rudimentary instruction in dance technique. My Dance Sampler and Dance Around the World programs pair relevant academic subjects (European History, African-American History, foreign languages, geography, etc.) with their dance counterparts. I also developed a program called Dancing on the Keyboard in which elementary school students learned how to choreograph both in the studio and on the computer screen using LifeForms.

At UCONN/Stamford where I’ve taught since 1981, I also frequently teach a Dance Appreciation course to people with a limited background in dance who need to fulfill a requirement. For them, I want to provide a broad overview of dance with studio classes in various techniques, dance history, ‘field trips’ to performances, video screenings, visits by guest artists, and a final project in which each student choreographs a dance and performs in original student choreography created by other members of the class. I believe that once they have seen what goes into a dance by creating one themselves, they’ll never look at the art form the same way again.

For my online courses for seniors (such as those at the Lifetime Learning Institute at Norwalk Community College), my goal is to enhance their lives by having them view and discuss extraordinary dancers and choreography that we watch together on video. These students are generally knowledgeable dance appreciators, so I want to give them an inside look into what they have been seeing on stage, making them more aware of and conversant with the details of the technique and artistry.

When I teach ballet classes to professional dancers, I concentrate on the artistry beyond the technique, and specifically on musicality. Everyone is technically proficient these days, but this proficiency sometimes comes at the expense of artistry. I try to bring out that intangible quality that separates the good from the great. It’s also a lot of fun to create challenging and stimulating combinations that exercise the mind and keep accomplished dancers engaged and interested.

When teaching ballet to teenagers in local dance studios, you don’t always find the ‘perfect bodies’ that students in schools like the School of American Ballet possess. What really interests me there is looking at each student individually and helping them become the best dancer they can be. That’s in part a rebellion against some of my past training, where I was often ignored since I never possessed that perfect ballerina body. So, for me, it’s very personal, and I make sure that my students have the encouragement and training they need to succeed.”

How has the dance field changed and how do you maintain the energy and motivation to keep creating?

“It’s better in that it is becoming more open and inclusive. Minorities are getting their well-deserved and long-awaited chances. But, and here is where the ‘worse’ comes in, for people like myself who have been toiling away, waiting for ‘our turn’ for years and years, we’ve been skipped over entirely. There are grants and programs out there now to which I can’t even apply because I’m not in a certain demographic or ‘an early career artist.’ And nobody was giving grants to early career artists when I started. I totally understand and wholeheartedly agree with the movement to bring people into the field who have been denied access because of prejudice, but I hope people see that the field needs to be opened to include everyone.

And as I’m getting older, I’m seeing that ageism is also a real factor. That’s one of the reasons I wrote Trap Ist – to explore that issue. Our field is ever-focused on the next ‘great new thing,’ but that goes too far sometimes; those of us over the age of 65 still have plenty of important things to express. And once you’ve reached a certain age, people think you should either be sent out to pasture in this youth-obsessed world or assume that you’ve already made it and need no further support. But that’s certainly not the case. Those of us who haven’t been lucky enough to figure out how to make the connections that would catapult our careers to the next level are still out there barely hanging on, pretty much the way we were in our 20s.

There is such enormous competition to get the few opportunities that currently exist. I’ve been applying for NYFA Fellowships and Guggenheims for decades and have not yet been selected for either. I haven’t been invited to things I’ve always wanted to experience like New York City Ballet’s Choreographic Institute or the National Choreography Initiative, but I keep applying because maybe at some point my number will come up.

It’s not all gloom and doom. Every now and then, a wonderful opportunity does come along, like this year when I was chosen for a Monira Foundation Residency to rehearse Trap Ist in October, and we also received a very substantial grant from LMCC’s ‘Creative Engagement’ Program. For every 30 proposals I submit, I’m lucky to get one or two. Think of all the time that went into writing all those rejected proposals that could have been spent making art and you get a pretty good sense of the lives of one-person dance company choreographer/directors. We spend all this time on administrative tasks like grant proposal writing just so we might actually make a dance someday. Choreography is the reward for doing all this other stuff! That is really what the life of the freelance choreographer boils down to.

I maintain the energy and motivation to keep creating simply because I have to. Years ago, I told myself, ‘Forget about the unfairness of the politics in the dance world. Just go do your work.’ No matter how much I’m ignored, I’m not going away, and I’m not about to let anyone else define my life. If I have something worthwhile to say, I’ll find a way to say it. I may never become well-known or win a MacArthur or whatever, but I’ll have lived, and will continue to live my life the way I’ve always wanted – creating art. And if by doing so I am able to make a difference in someone else’s life, someone who sees the work and is inspired by it, then that’s a bonus.”

Felice Lesser Dance Theater will present Trap Ist at New York Live Arts from December 1-3. For more information, visit www.fldt.org.

By Charly Santagado of Dance Informa.