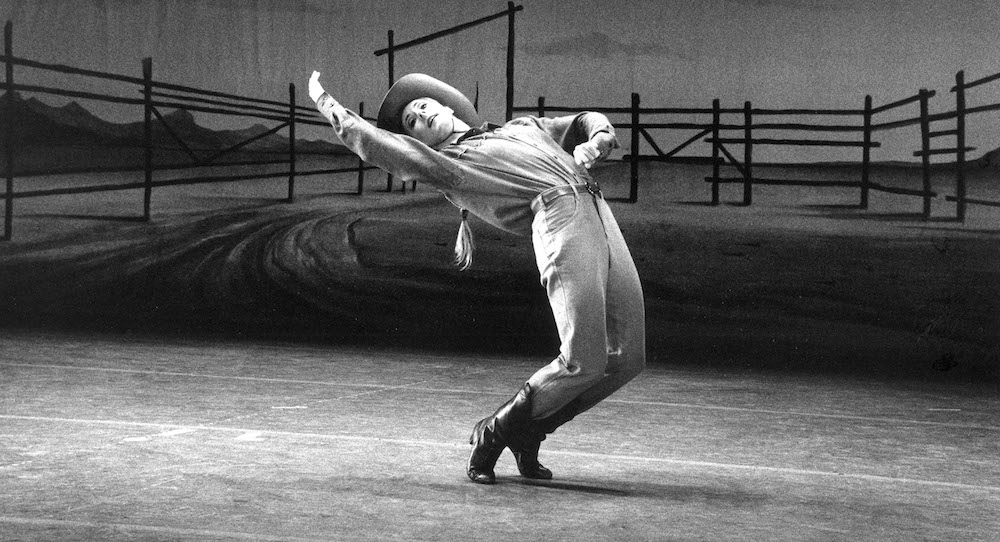

It’s the 80th anniversary of Rodeo, the ballet that launched choreographer Agnes de Mille’s career in creating Americana ballet. Rodeo tells the story of a young, headstrong, misfit cowgirl looking for love. We discussed its legacy 80 years later with Diana Gonzalez-Ducert (former rehearsal assistant to de Mille and Associate Director and Repetiteur for The De Mille Working Group), and two dancers who have reprised the original Cowgirl role over the years: Kathleen Moore (former principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre [ABT]) and Jenna Rae Herrera (principal dancer with Ballet West.)

Agnes de Mille herself said of Rodeo, in a letter to her future husband, that the ballet is “about Texas, and the way I feel about you.”

So many years later, the meaning of the ballet has compounded – finding relevance in new modern moments.

Gonzalez explains its evolution – “Rodeo premiered October 16, 1942, less than one year since America engaged in World War II and young soldiers were shipped overseas. The country was ready for something that could boost morale and try to define an ‘American spirit’ with both humor and heart. Rodeo is a ballet, and yet the choreographic language was not the codified ballet language brought over from the European continent. Instead, it smacked of American gesture and energy,” which the Russian dancers of Les Ballets Russes, whom the ballet was originally set on, struggled to imitate. “After the first few rehearsals of ‘roping,’ ‘riding,’ ‘lurching,’ and ‘sitting on a horse,’ many of the Russians said ‘It is not dancing’ and left.”

The individualistic spirit of the Cowgirl is distinctly American. “The story of an awkward outcast still tugs at our heart strings. In one way or another, we can still relate to the Cowgirl, and we cheer her on in the Hoe-Down at the end of the ballet, as she wins the challenge of being proud of who she is.”

Moore notes, “This Cowgirl really was Agnes.” De Mille not only choreographed the role, she was the first to dance it, too. “Agnes at the time hadn’t had big successes; she was fragile. She came to ballet late, she didn’t find the classical stuff easy. She was great friends with Martha Graham, and sought guidance from her, but Martha encouraged her to stand on her own two feet and to keep trying. Through that process, Agnes became this confident, courageous, feisty, funny, persistent, imaginative person. Her Cowgirl is all those things.”

Says Herrera, one of Rodeo’s most recent Cowgirls, “I couldn’t help thinking she is just so determined. How many times does she literally get knocked off her horse, get back up, brush herself off and keep trying? Staying true to yourself is something that stuck with me while performing the Cowgirl, never apologizing for being who you are.”

In the Americana brand de Mille became known for, those qualities resonate as deeply American, especially in a time when the U.S. was fighting for American ideals and identity. That identity is part of what keeps de Mille’s ballets pertinent and relatable today. “De Mille was passionately interested in history, a people’s culture and human behavior,” says Gonzalez. “She was always searching what could be ‘intrinsic’ in a culture. Most of this searching was through women’s narratives that revealed…their inner lives. De Mille created a venue for this expression of women’s stories, which are also universal.”

So do dancers find taking on the iconic Cowgirl role intimidating, especially given de Mille’s reputation for specificity? Rodeo was the first ballet de Mille did that she demanded to have full control of, from music, to costumes, to casting. Even when it was being set on ABT in the ’70s, she would bring on Broadway dancers she had worked with to play the Cowgirl. Moore says with that kind of control over the ballet, she was comforted in knowing that de Mille specifically chose her.

Moore had also been working closely with de Mille previously, while de Mille choreographed The Informer on her. She felt a kinship to the choreographer. They both had long red hair, braided for the Cowgirl role, neither identified as the stereotypical classical ballerina, and both had performed the same role in Antony Tudor’s Dark Elegies. Moore was just about to get married, which is where de Mille was in life while she was creating Rodeo. De Mille even offered Moore her wedding veil.

Comparing Moore’s personal experience to Herrera’s, who was handed down de Mille’s direction from secondhand sources, how did Herrera stay true to the original intentions?

Having Gonzalez by her side with a binder of notes and quotes from de Mille, recorded during the original choreography process, definitely helped. “Getting to hear what Agnes herself had said about how the Cowgirl is feeling in this moment or that one, that was valuable to have those intentions lead us through the ballet. It always felt to me like a beautiful narrative, like Diana was reading us a story. That helped bring the Cowgirl to life for me.”

“Diana and Paul also allowed me to put my mark (small as it was) on the role. There’s a moment in the ballet, my favorite, after the Cowgirl gets rejected again by the Head Wrangler, where she steps out on the porch and is looking out at the land. Even though I was just standing and looking out at the audience, I loved that moment. And then in any of my interactions with the Champion Roper, we got to play around and add our personal touches. Those were moments when I got to see me inthe Cowgirl.”

Moore echoes that feeling. “The interactions, the conversations between the dancers that the choreography gave us the structure for. Those will be different between different dancers.”

But the rest stays true to intention. “When Rodeo is successful,” she says, “the timing and the steps are specific, even if it looks natural in the moment, even in the way she pulls up her pants. We spent hours on those details.”

Gonzalez knows it’s those details that translate the intent of the piece through the years. She recalls, “(Agnes) once said to me in rehearsal, ‘I can’t remember a step I choreographed yesterday, but I can remember how someone buttoned their coat 30 years ago.’” Those human gestures, and the importance de Mille placed on them, is what marked Rodeo as a relatable and enduring story, rather than simply aesthetic movement.

Gonzalez speculates, “I think in difficult times, as we are in now, an audience wants a story and simple human gesture that they can relate to – an experience that is perhaps less abstract and more…a moment of entertainment. I think de Mille still brings that to an audience. The recent Ballet West’s premiere for Rodeo’s 80th anniversary and the audience’s enthusiastic reaction showed that.”

By Holly LaRoche of Dance Informa.