The Wilbury Theatre Group, WaterFire Arts Center, Providence, RI.

March 10, 2023.

“Take a risk!” I can’t count how many times I’ve heard it from dance teachers. The courage to try something new, to step onto an untrodden path, is essential in art-making. Otherwise, the art we experience is only that which we’ve experienced before, and artforms as wholes stay stagnant. At the same time, after we take those risks, refinement is necessary. Audience and artist experience are both important parts in the mix. Taking in the 2023 Motion State Dance Festival had my brain chewing on these matters.

The program kicked off with one I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing before (or at least an earlier iteration of it): Doron Perk’s Grandfather Visit (2021). I first saw a filmed version of it, and – with Perk performing right before us – his kinetic ease and keen musicality were even more palpable. He took his time to build an atmosphere with this work, something I noticed even more this time (or perhaps an effect of how Perk has evolved the work in the past year and change). With both calming and unsettling elements, the work leverages Perk’s uniquely supple physicality to bring us deep into an inner world.

I’d also seen the second work in the program – Baye and Asa’s Suck It Up – once before. The twenty-minute dance film is a bold, memorable exploration of modern pressures on men. Seeing it on a bigger screen this time (the first time being on my small Chromebook screen) also allowed me to more so appreciate the nuances in Baye and Asa’s performance — from facial expressions to characterized physicality to movement quality. On this second viewing, I also saw its humor more than its absurdist bent. Other audience members chuckled along with me. It just goes to show how various layers of a work can be uncovered, and then enjoyed, from multiple viewings.

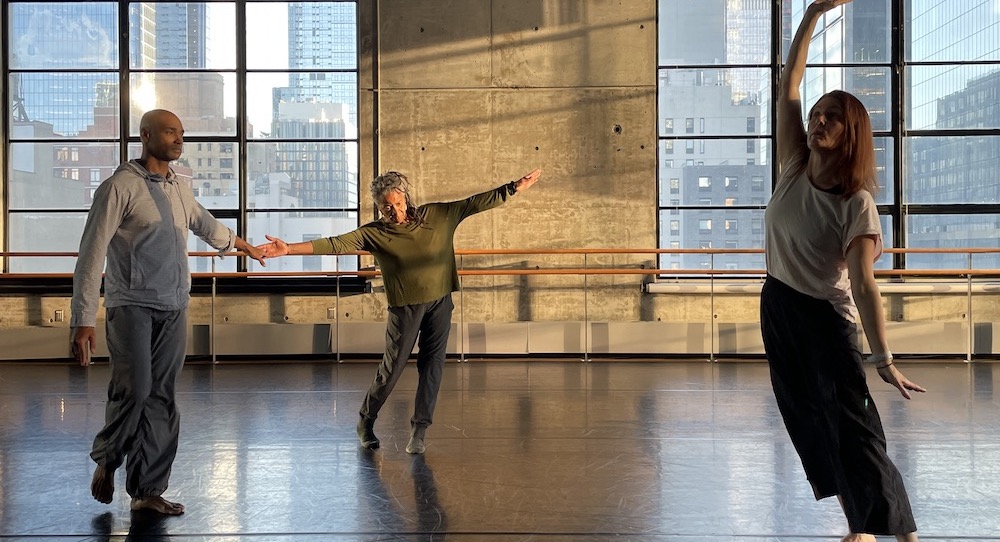

After intermission came works I hadn’t seen before – beginning with Tether from Angie Hauser, Darrell Jones and Bebe Miller. It’s a cozy exploration of kinetic possibilities within time and space – and how those possibilities expand with multiple embodied agents engaged. The trio of dancers investigated movement more pedestrian than athletic – yet clearly with its own sort of virtuosity: of integration, of release, of smoothly riding waves of momentum through the body. Musicality was another memorable element of the work; that physicality also – just as smoothly – rode the wave of rhythmic possibility in relationship with the score (from John Cage and Dream).

Another intriguing element in the score was voiceover of two words (only two words), alternating: “rest” and “stop”. Guiding these dancers, these words were their own sort of tether. Possibility fully co-existed with that tether, however – and possibility really felt like the operative idea here. It seemed a mystery as to what the dancers might examine next: in relation to space, time and one another. In that way, they offered an element of children at play, with full openness to what they could experience.

Certain sections could have been condensed and edited down, in order to feel like they weren’t dragging. Yet, that sense of open, curiosity-fueled discovery I nevertheless greatly appreciated. Indeed, the spare, unassuming nature of the work might be different from what some audience members might expect from a work of concert dance. As such, there’s a courage to presenting a work like this. The ultimate impact of such courage, one might argue? A work like this can reveal that the investigation, and the easeful integration that it often sparks, can be enough.

The following work, Verena Billinger and Sebastian Schulz’s film Car Walk (2021), even more so teased at the boundaries of what dance art can be – and, with cohesive elements of movement and sound, I’d defy anyone to say that it’s not that. With nothing but a camera, a group of movers, a car (with brakes off), a parking lot and an open sky, the collaborators created something both fresh and pleasing to the senses.

To begin the work, a camera panned in on a car in a parking lot, the sky clear and the day bright. The dancers began their play with how they could move on and around the car, and move the car itself – an exploration that would continue throughout the work. In turn, the dancers pushed the car or found other actions: rolled over the roof and hood down unto concrete, straddled roof racks, rode along with feet on door frames and arms on an open door.

A satisfying visual was all doors and the hatch opened and fanning like sails – the car like a boat in the ocean of this parking lot. All throughout, the only score was that of gravel under the car’s tires and the sounds of cars passing by (presumably on a nearby highway) — an oddly calming and satisfying score at that.

Overall, I found the work energetically and aesthetically satisfying, but not with drawbacks. Frames showing us drivers inside the car felt more structurally fitting for an ending section, and otherwise took me out of the organic flow of play with the car. Certain parts could have been condensed to avoid that dragging feeling, similar to with other works in the program thus far. Deep, free exploration is often vital for the process, and for artists feeling true to their creativity. Yet, if not then refined and edited down, for some audience members it can feel like tip-toeing toward self-indulgency.

The last piece, Izumonookuhl from Aretha Aoki and Ryan McDonald, walked further out on to that ledge: taking daring risks, often resulting in something intriguing, but perhaps also walking closer to self-indulgency as a result. The work-in-progress began with a rockstar vibe, Aoki grooving out in a sequined dress. Entrancing visuals across the backdrop – psychedelic, electric, vibrant – matched the rhythm of the music and electronica movement. That moved into a section with more technical movement: grounded, absorbed, integrated. I found this the most satisfying section. Aoki, sinking toward the stage floor, extended one leg while she stabilized with the other. From a firm center, she reached out into periphery with active arms. Fully absorbed in sound and movement, she slipped into trance.

From there, the work moved into sections of repeated movements: ball changes with torso rolls, continuous headbanging. I can understand the artist’s likely intention: to build something meditative, hypnotic. I can’t say that was my experience. Interestingly, it might have been if the sections were pared down to something shorter. The length of each section is what took me out of that absorbed experience, it felt like. The advantage of this being a work-in-process is the time and space to see what does and does not resonate. Every work of art has its process and life-cycle.

What I do very much commend is the risk-taking. If we look beyond audience experience, we do need that kind of courage to move forward as an art form (every art form does). And many aspects of movement and production did appeal to me: explosive yet also cohesive, daring but also straightforward. A poem guiding another section also felt like an intriguing choice, one offering a pleasing sensory shift within the work.

All in all, something created for an audience is separate from what’s created for an artist, for the experience of the process. Both are valid and meaningful – we should just be clear about the distinction. And to be clear, this writer believes that the extent to which artists should center audience experience in their process is fully debatable. Yet, it is something to be thoughtful about. That’s a good discussion for a community of artists to have as we move the work forward.

At the very least, the program had me thinking in these sorts of ways – as well as inspired to take my own sorts of risks. For all of the moments of creative alchemy that I enjoyed, and for leading me to (I hope) think productively, I can’t think of a better way to have spent that night than at Motion State Dance Festival’s Saturday night programming.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.