Released in 2019.

Streaming now.

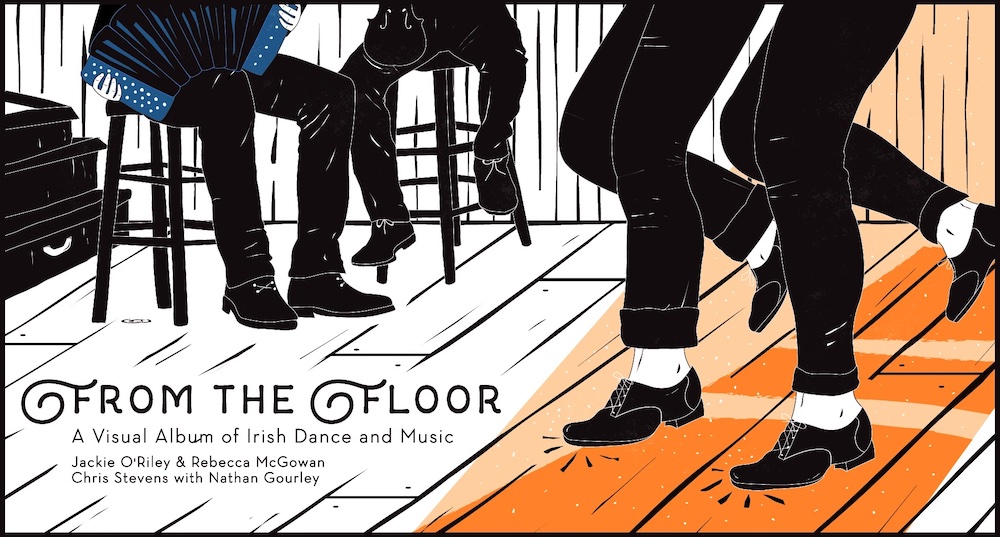

The little gems of art that we can find by chance: it can be sort of amazing. From emails back and forth with one of the artists, and a bit of digging into her body of work, I found Jackie O’Riley and Rebecca McGowan’s From the Floor – an Irish dance visual album featuring various styles within the form (all “hard-shoe”, generally considered “old style”, versus the more modern “soft shoe” style), produced by Matthew Olwell and Katie McNally. The film was released in 2019. Although that can feel like a whole other lifetime ago (with all that’s transpired since), the work’s joyful energy and intentional craft make it timeless enjoyment.

The film features two musicians (Chris Stevens on button accordion, concertina and Nathan Gourley on fiddle), O’Riley and McGowan, all performing together in a tastefully humble rehearsal space. That’s it – just their music, movement and sound – and it’s enough. In fact, there’s an unadorned rehearsal/class feel from the very start; in opening shots we see a rosin container (for the unacquainted, a material that dancers use on their shoes to keep from slipping) on the windowsill.

The dancers wear simple, moveable slacks and blouses in a stylish dark palette, with their hair neatly placed: intentional, neat, and nothing overdone. The sun shines in through the ample windows, adding to the brightness of the music, sound, and movement. To whit, the work to come feels just plain joyful; who could be in a bad mood with this vibrant music and movement? Yet, it’s a natural joy, not pushed at all. It just comes through the magic at hand.

After those opening frames, the dancing starts with a solo for McGowan, until O’Riley joins in to create a duet (Jigs: Maid on The Green/Paddy Taylor’s). Videography and video editing (by Louise Bichan, with assistance from Ethan Setiawan) intersperses shots of the dancers’ feet with those of their whole body. That’s a nice balance that allows us to see the richness of the footwork, but also the whole body engaged – as one would experience the form danced right before them.

McGowan and O’Riley are precise, especially with their footwork and sound (as virtuosity in the form calls for), but also move with ease in their carriage. Their arms are by their sides, yes – per the common mental image of Irish step dancers (à la Riverdance) – but not held there stiffly. They allow the momentum of their footwork to naturally travel through all of them.

Next comes a solo for McGowan, a Set Dance: Garden of Daisies. This section in a style that’s a bit more jumpy, with her ankles shifting side-to-side, and less lightning-quick than the style of the first section. The shift in music – and correspondingly in movement – is quite clear. The third section, Reels on the Board: The Curragh Races/Larkin’s Beehives, features both dancers. It pushes the compelling cinematography forward, evolving along with the movement at hand; the frames mostly focus on their feet, shooting at a level angle from the side. That approach supports the small, meticulous nature of this section’s steps.

An interlude presents just the musicians, with close up shots of their nimble fingers at work. That’s a kind of dance, too, their partner their instrument. A duet following that, Hornpipes: The Flowing Tide/The Humours of Tullycrine, has a more lateral (side-to-side) feel to the movement. A gentle sloping line from one dancer to the other brings a pleasing organization to their bodies in space. The steps are quick, dynamic, and riveting in their layering.

A subsequent solo for O’Riley (Jigs: The Walls of Liscarroll/The New York Jig) features close-up shots on her feet, and more of a forward-and-backward (sagittal) directional feel. The dexterity of her ankles and her rhythmic precision pulled me right in. The last section, Hop Jig/Reels/Hop Jig: Silver Slipper/The Piper’s Despair/Trip to Durrow/Silver Slipper, brings McGowan back for another duet. They face each other and then away from each other, as well circle each other in space. They also alternate solos, passing the proverbial baton.

This section has a bit more active movement through space, as well as varied structure, than the prior sections. That makes it a good choice for the film’s closer (they say that audiences remember the openers and closers best!). It also goes to show that even while at first this form could feel static in space, as compared with other dance forms, there really are lots of possibilities at hand – and these artists found them for this film.

The dancers end by looking to the musicians with a smile – which feels like a lovely acknowledgement of them as collaborators. Before the credits roll, they all share a relaxed moment of a laugh and physicality that speaks “aaaaah, we’re done, we did it, and it was great!”. All in all, From the Floor is a thoroughly captivating kaleidoscope of styles within Irish step dance, also with a pleasantly minimalist approach. Sometimes adding bells and whistles beyond music, movement, and sound doesn’t serve creators or audiences. Sometimes, indeed, those things are far more than enough.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.