Book: Movement at the Still Point: An Ode to Dance

Author: Mark Mann, Rizzoli International Publications, March 2023.

“At the still point of the turning world /….at the still point, there the dance is.” (TS Eliot, “Burnt Norton, 1936) That’s the first thing we read in Mark Mann’s Movement at the Still Point: An Ode to Dance. As quite an understatement, that’s the very tip of the iceberg of what this book offers. It’s a dance photography book, but also so much more. It paints a picture of the art form of dance, in qualities that mirror the dance community itself: scrappy yet richly layered, Spartan yet kaleidoscopic.

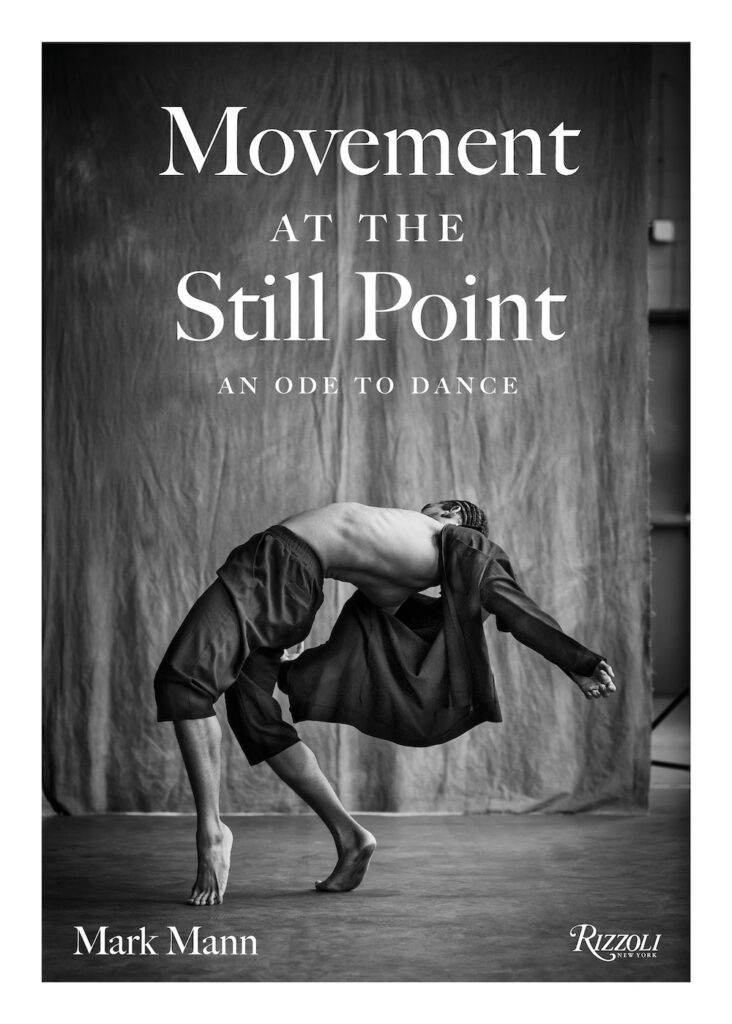

Using a 120mm lens, Mann captured dancers in an unadorned New York City studio apartment. The only objects behind the artists are a white curtain and electrical wiring in the corner. Some of the included dancers contributed short statements, expressing their truths as relates to their beloved art form: sharing their journey in it, what it’s meant to them, how they hold the dance community in their hearts and souls.

While relatively brief, these statements speak volumes upon volumes: therein that layered richness within something seemingly simple and straightforward. In the same way, these individuals are unified as dancing humans: devoted to an art form, commendably skilled in that art form. Yet, as a group, they also hold so much multiplicity: in a range of ages, races, ability/disability, body types, and dance styles in which they specialize.

Mann also included “household name” dancers – such as James Whiteside, Misty Copeland and Carmen de Lavallade – as well as less well-known dancers. Level of notoriety doesn’t seem to matter. They’re all dancers: all fully committed, capable, and worthy of being seen and heard. They all have their role in the dance ecosystem. I first noticed this range of renown while looking through the index of dancers in the book’s early pages (which is accessible and functional through listing which dancers are to be found on which pages).

Chita Rivera’s foreword soon follows that index (and, of course, we’d consider the legend among the household names in the text). She notes the certain romance of Mann’s plain, one might even say gritty, NYC photography studio. Keeping this in mind, it hit me while reading: the minimalist environment in these photos is cohesive with Mann’s black-and-white style – and there’s a certain beauty to that cohesion. It’s all in the real world – nothing superficial or fabricated. The “beautiful” and the “ugly” meet there, at that authenticity.

Rivera also highlights just how much the dance sector has come through over the years (most notably, the AIDS crisis and – more recently – COVID lockdowns). That resilience speaks through the following pages; it’s clear that each dancer in this book, in their very own way, has persisted – has refused to let immense challenges keep them from their vision for themselves.

Wonderfully so, Mann’s photographs let that unique grit shine through each photo. Some images show them in “dance” photos, as we might understand them, and some portray them as simply human — just their face, or doing nothing more than sitting (with presence) on a stool. Dancers are human after all, not moving robots.

Toward the former (the more “dancey” poses), the photos offer a feast of shapes, gazes, ways of being in the body in space; some highly technical (for example, contemporary dancer Alison McGuire presenting astounding flexibility and articulation, in a shape of a deep backbend and elbows bent in a seemingly superhuman fashion); some with the grace of a simple relevé and hip placement indicating movement off-center (Tiler Peck and Jonatan Lujan); some with powerful presence in an elemental dance position and intent gaze (Skylar Brandt); others mid-leap (Heather McGinley). That’s all another iceberg tip.

Those short written testimonies hold their own multiplicity. Some dancers attest to their histories and lives in dance, their love of it; Al Blackstone shares how he could “see himself” doing something else, but is so glad that he doesn’t have to. Some, like Marla Phelan, note their passion for catalyzing change towards greater equity in the field. Some like Alonzo Guzman and Megan Fairchild poetically describe the immediacy in the dancing moment, the kinetic and sensory experience of it.

Other artists in the book describe the struggles of growing up and how dance was a refuge, or presented its own obstacles to individuality and being true to oneself (Abdiel and Tyler Maloney, respectively); the pouring out of the self in expression and storytelling (Chalvar Monteiro), and the exhilarating exhaustion that results (Alexandra Hutchinson). There’s much, much more there that one can take in with their own reading.

There’s also striking variety to the styles of dance represented: breakdance, ballet, contemporary, vogueing, Broadway, modern, postmodern, hip hop, hustle, ballroom, tap, flexn. Culturally-based dance forms – such as Irish Step Dance, Flamenco, Bharatanatym – also have a presence. I felt it deep in my bones, bones that have moved through a plethora of dance styles themselves: dance can be so much. It is so much.

One thing in particular I craved more of in the book, from having a sweet little taste. A lovely shot depicted A.I.M by Kyle Abraham: the full company. It led me to wonder what more full dance company shots could have brought to the work, physically, energetically, aesthetically – or even more trios, quartets, and quintets (there were a handful of duet photos). Perhaps the logistics of scheduling larger groups of (already very busy) dancers made more of such photographs not possible. It’s also already a thick text, and there’s nothing in there I personally would throw to the cutting room floor!

I also pondered how Rivera, and Mann himself, noted how this project was Mann’s first time photographing dancers. That was astounding to me, because he seemed to bring an implicit understanding of dance and dancers to the work: of shape, line, gaze, gesture, level, et cetera. No doubt the featured artists assisted with that – yet still, Mann was the one behind the camera. Mann’s perception of the field as “inclusive”, as an outsider to it, was also intriguing to me. That’s of course anecdotal, just one person’s impression. Yet it perhaps points to that compared to the wider world, the dance sector is actually doing fairly well there.

Loni Landon, Mann’s sister-in-law, closes out the text with a cogent, honest Afterword. She shared more on how the project came together, and how it captured those unique “in between moments” — the immediacy that truly makes dance thrilling. She underscores the notable feat of gathering together such a group of artists from so many disparate fields, in quite a challenging time for the field and the wider world.

Such challenges have many dancers “facing their true selves”, she also notes, and that this book reflects those true selves – to me, as much as could be possible in mere images and brief words. It’s a mere snapshot – albeit a vibrant, lush snapshot – of the wonder that dancers are: in their diversity and in what they share.

All of that: it’s dance moving forward. It’s the dance of the 2020s and beyond. It’s the polychromatic, polytextured tapestry of dance, on human canvas. I say thank you and “brava!” to Mann, Landon, Rivera and all featured dancers for presenting that human tapestry in two-dimensional form.

Movement at the Still Point: An Ode to Dance is available at booksellers everywhere.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.