The realm of casting is an interesting place. And the world at large has always had a fascination with it.

Those of us who have spent a large part of our lives doing the casting of live performances, TV shows, film, one-off events, seasonal show runs and the like, have privileged knowledge of how the casting process typically works. We know the complexities of filling a role with the right performer. There are character breakdowns to follow, and on top of that there is each creative team’s personal preference to consider.

But the way most show productions work, whether it be musical theater, traditional theater or commercial projects, there is a script or scenario that will have characters. And in most productions, these characters have descriptive parameters that hired performers will have to match and fulfill.

In most productions. But not all.

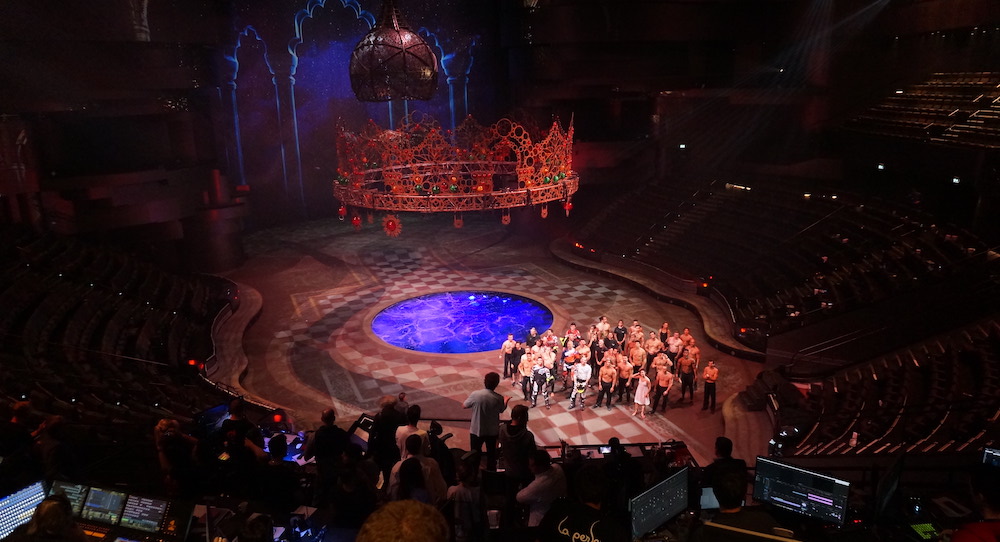

Franco Dragone was one of the most iconic creators of multidisciplinary non-verbal theater. His claim to fame was through the early works of Cirque du Soleil, and it was his creative input as director that gave Cirque its signature brand of stage poetry that made the company stand out from the crowd. His creations — some of the most well-known being “O”, Quidam, Alegria and later on, The House of Dancing Water in Macau created through his own company, Dragone — were spectacles to behold, sparking the frequent comment, “I’ve never seen anything like it” from audience members. Dragone’s shows were rife with uniquely personal moments, breathtaking images and, most of all, poignant, touching characters. The casts of his shows were also like none that had ever been seen before in mainstream entertainment.

In 2022, Dragone passed away, and his presence will be greatly missed. His passing, though, reminds us, as professionals in the casting field, of his unique way of casting and creating characters. Casting for someone like Dragone was an antithesis to the traditional casting process, which typically begins with a character breakdown as described in a script, followed by auditioning performers who fit those character descriptions.

But for Franco, the uniqueness and genuine aspect of each performer’s personality was the cardinal facet. He never created characters based on a script that had already been written. So, in Dragone’s world, the traditional way of casting did not make much sense.

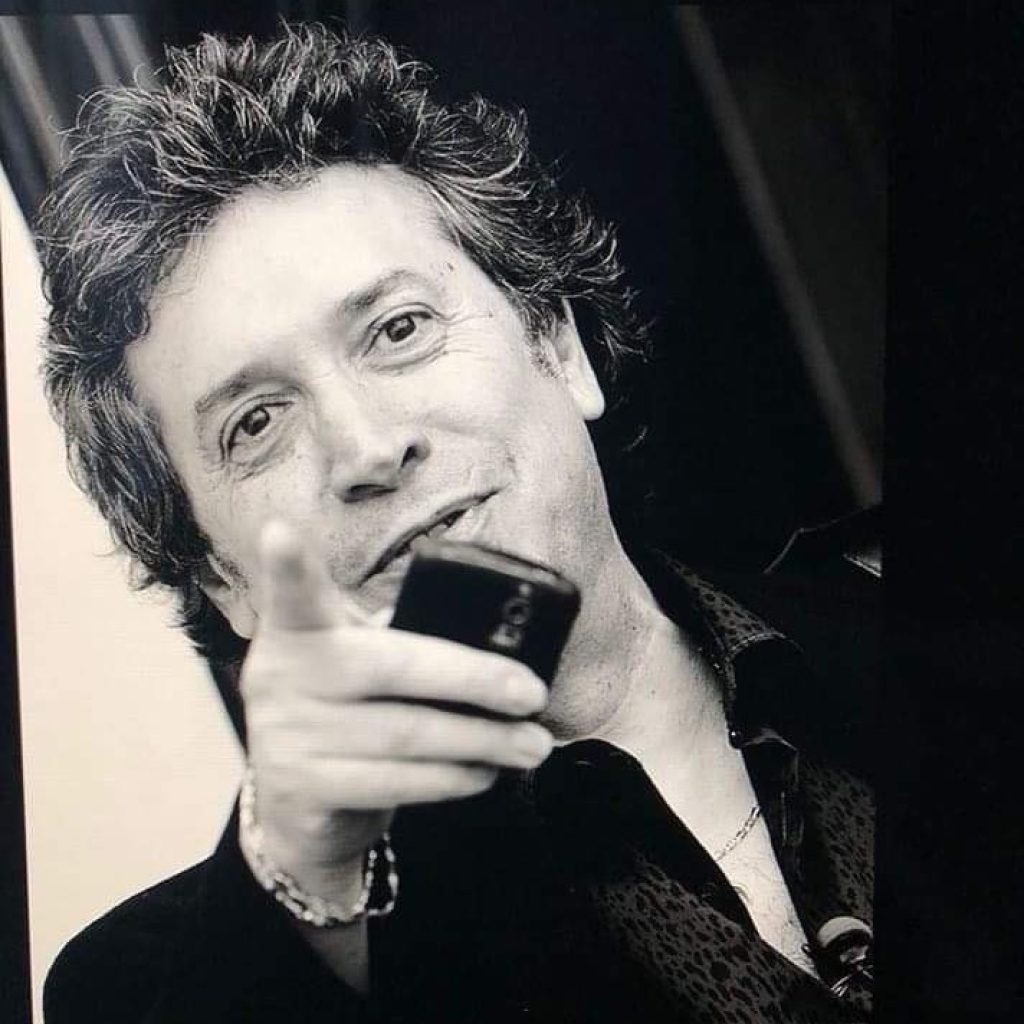

This year, 2023, to fill the artistic void left by Dragone’s death, the Dragone company appointed a new artistic director, Filippo Ferraresi. A native Italian from a small village near Rome called Gallicano nel Lazio, Ferraresi worked with Dragone for many years — years through which he got to know Dragone and his creative process on an intimate level. In other words, he deeply understands the way Dragone thought, the way he worked and the way he chose his casts.

“Radically different from the Broadway approach,” he says, “like, the opposite. Franco always used to say, ‘Show me who you are. What interests me is your universe.’ First thing. He constantly kept repeating this to artists and designers.”

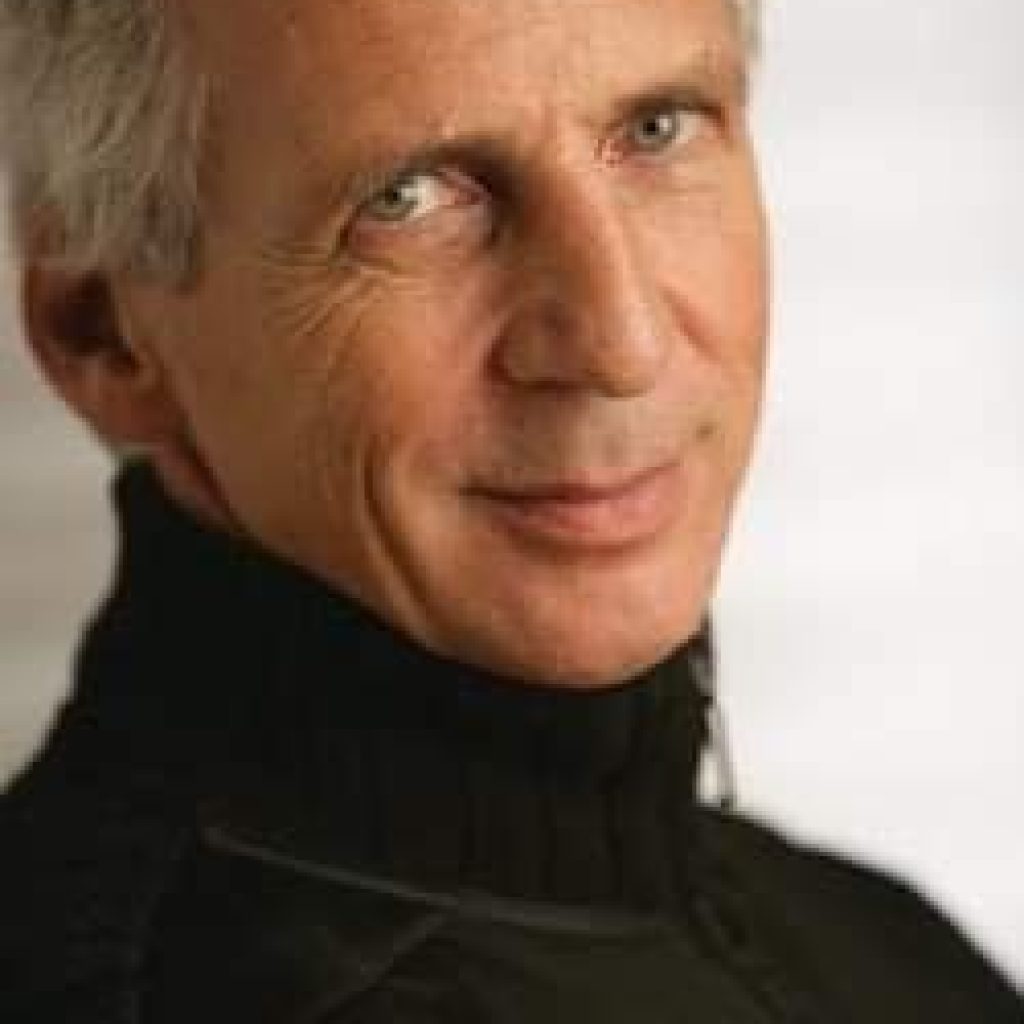

Rewind back to 1982. A young man named Gilles Ste-Croix in Baie-St-Paul, Québec, Canada, had begun a small group of stilt walkers that did street performances and had succeeded in building a following. By the following year, the group had begun putting together ideas about building a project where street players would perform under a big top. In 1984, the project would finally come together under the name of Cirque du Soleil.

“When we were building a show in ‘84 and ‘85,” says Ste-Croix, “we were using the circus school in Montreal to do these shows. Guy Caron was the director of the school, and he invited different people to teach at the school. Franco Dragone was invited. [Franco] was working in, I would say, politically-oriented theater in Belgium, in Brussels, where he was doing exercises and putting on some collective shows with people from factories or from social groups. Guy Caron invited him to come to work with acrobats that were at the school, and that’s how he started to be connected with the group that we were part of.”

That was the beginning of what would later mark performing arts history. Ste-Croix, as one of the original founders of Cirque du Soleil and the principal person who developed Cirque’s first shows with Dragone, also has deep insight into Dragone the creator, and the type of performing artist that Dragone wanted to work with.

“The approach of casting — Franco didn’t have any idea how to go about that,” he says, “so he left that to me. In ’89, there was no artistic department. So I started to develop a way of casting at festivals, finding completed numbers. At circus schools as well. And also by doing some auditions.”

Ste-Croix continues, “Franco would say, ‘I don’t care what you bring me; what we need is top quality artists. I don’t want beautiful, fancy… I want some gueule [“gueule” is a slang word in Quebec French that refers to a striking or very unusual face or look]. I want characters. So these people had to have more than just a beautiful walk. No, they had to have something inside that Franco would go and grab, and say, ‘Ah, we’re going to go with that!’ Instead of just the polished side of somebody.”

This is what made his cast fit his characters so well — by creating the roles around the unique features and abilities of each individual cast member, instead of writing the role first and then finding the performing artist with the closest fit. The diametric opposite of the traditional casting process we are all familiar with.

But this is in large part what made his creations so unique, so emotional and so engaging — a story with perfectly harmonized characters, because it was the personality of the performers who created the story.

Ferraresi explains, “Franco always used to say, ‘I don’t have ideas. I know how to recognize good things. I know how to see.’ He used to say that his biggest quality was to be an antenna and capture the vibrations and the trends, and see what could be new or ‘wow’ or funny or tragic for an audience. And so, for example, in casting auditions — more than casting, in the workshops that he used to do, like theatrical workshops — no roles were assigned before that period. Impossible! He used to see people, make them walk on a stage and work with them, shaping their peculiarities.”

Ste-Croix adds how the personality of music coupled with the personality of the artists would drive the personality of both the resulting characters and the resulting show compositions.

“Every time Franco worked with staging, when he worked with workshops or he worked with dance, he always had some music prepared because he was a very musical person,” says Ste-Croix. “He would find music that brought images in his head and he put them out and wanted people to move on it, to see how they would react and how it would make him react. To see them move on that music. That would influence the creation of the music.”

Ferraresi explains that the movement essence of an individual would also influence other aspects of a Dragone show. “Another thing about casting, which is very important for Franco — he never assigned a costume, never, before seeing the body. He used to say, ‘The costume designer proposed a sketch. Beautiful. I accept the sketch. But I don’t know who to give this costume to, because if I don’t see how a body moves, I cannot just assign blindly beforehand. It’s the collision between a costume and a body that makes the character.’”

Ferraresi continues, “And so the casting was very important because Franco… the only direction he used to give (beforehand) was by discipline, by big fields. Like, he used to say, ‘I want eccentrics,’ or ‘I want mimes,’ or ‘I want actors.’”

Ste-Croix explains that “it was really a collaborative creation, but it was also really a work-in-progress. We worked like, maybe six months in finding what the show is, and what the casting is, the music, the set. This is the way that all this would behave into a nucleus that would make it possible to stage. Then, we would start the staging — little moments, we put them on the side. Little moment numbers, then we added characters around it to make it not just acrobatic, but make it a theatrical acrobatic moment. So it was really a way to build a show out of nothing, out of just interest to do something new, but something unique.”

For anyone who has seen Dragone’s creations, I think it is safe to say “mission accomplished.” His work has touched millions of people across the globe in unforgettable ways. Although much of the work he did was impressive because of its grand scale and because of the high skill level of the performers, his success in remaining memorable is primarily linked to emotional poetry of character. Audiences tend to forget the details of what they saw, but they do not forget how they felt.

Just as people I know who have worked with Dragone all tell me that it’s an experience that they, too, will never forget. And it is implausible that this would not be related to the particular way he saw the world, the way he saw people, the way he saw characters, and the way he chose his artists and built memorable characters on the singularities that make each person different from the next. Unforgettable characters from an unforgettable man.

“Franco was like a brother,” says Ste-Croix. “We went along for 10 years into creation. I was really learning how to look at the world with him and read the stage, in a sense that with an open mind you let yourself flow in the creation. So when Franco left, he left me with these memories. He left me with this wonderful period of my life, which I can look back on and I can really enjoy and say, ‘I lived that.’ I have done eight shows with Franco Dragone.”

He recounts an analogy.

“I heard Paul McCartney say, when they asked him ‘What do you remember of the Beatles?’ He said, ‘Hey, I played with John Lennon.’

“And I thought it was like, ‘I worked with Franco Dragone.’”

Ste-Croix continues with a smile of reminiscence that makes us warm all over.

“I can say that.”

By Rick Tjia of Dance Informa.