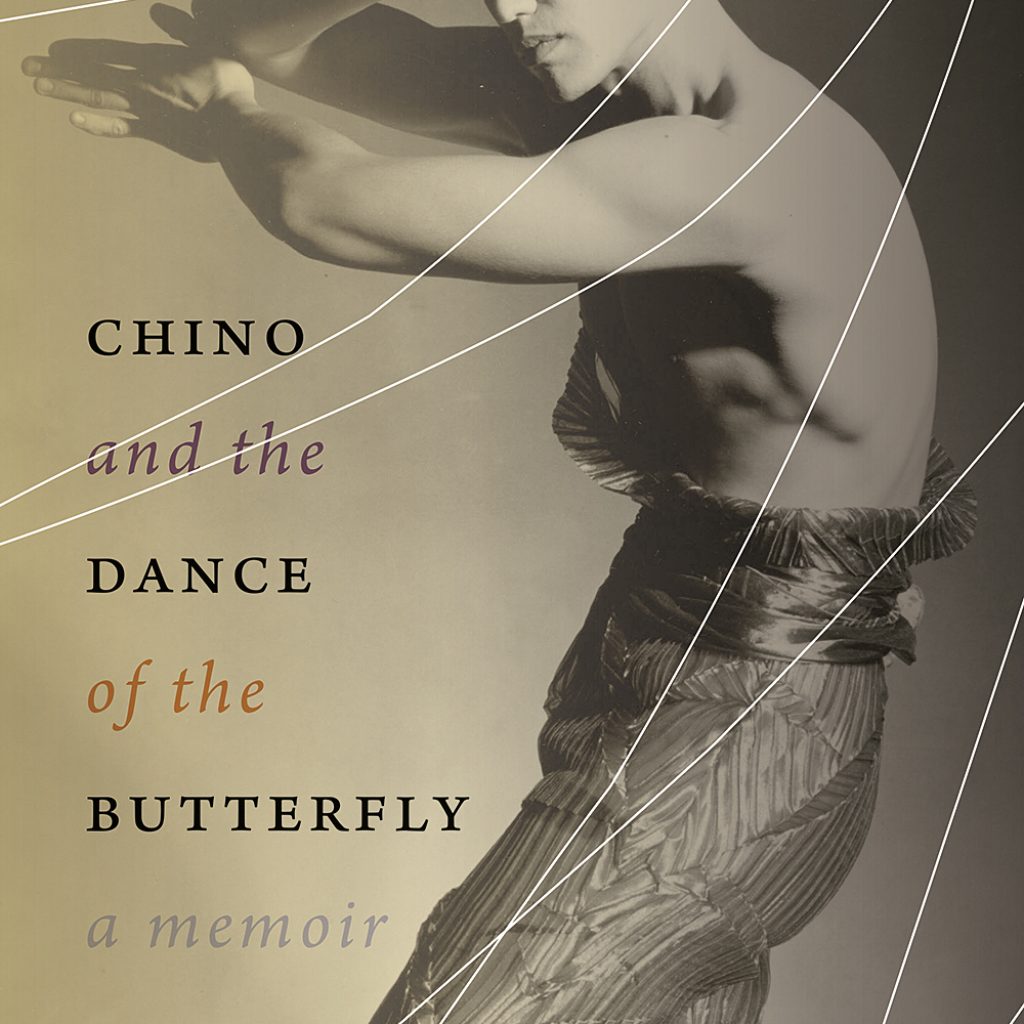

Book: Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly: A Memoir

Author: Dana Tai Soon Burgess, University of New Mexico Press, September 2022.

Good writers write about what they know, they say – and one could argue that it’s the same of all artists. When we shape and color the personal into art, with intention and heart, the personal becomes universal. I was reminded of these truths while reading the memoir of Dana Tai Soon Burgess, artistic director of Washington, D.C.-based Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company, and dance diplomat, writer, educator, and advocate.

Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly: A Memoir paints a picture of Burgess’ unique path but also reveals truths common to the path of all dance artists. His prose is just as poetic is his atmospheric choreography – lyrical, yet eschewing the needlessly esoteric. Honest and rich, his stories can deeply engage both the heart and mind.

The earlier part of the text is more linear than the latter. A memorable preliminary chapter describes a core memory for Burgess: dancing with migrating Monarch butterflies as a curious, movement and expression-craving youngster. Burgess himself as a migrating butterfly – exploring and seeking – is a powerful extended metaphor that he employs throughout the text.

Other notable themes and scenes from his early life range from the heart-wrenching (bullying, family poverty and search for personal identity) to the heart-warming (putting on living room performances for his parents and brother, and making friends with those also feeling marginalized and searching for their own identity). Burgess’ unique blend of fortitude, creative curiosity, and instinct to shape story and feeling into art; it seems to have always been in him.

Like many male dancers, Burgess started dancing later in life – yet it wasn’t his first foray into structured movement. He first encountered movement’s healing and empowerment through the martial arts. It’s one of many kinetic influences that would surface in his choreographic work later in his life. He began dancing in earnest (apart from a few classes at a hometown dance studio) in college. It seems that a natural affinity for the art form was there to support his fascination with it, and growing love for it, as he got deeper into formal training.

As he notes, Serendipity and Synchronicity (he capitalizes those, anthropomorphizing them into some sort of benevolent spirit) were also on his side. Although he left his dance studies at the University of New Mexico before obtaining a degree, from the lure of professional contracts in Washington, D.C., he met choreographer Maida Withers. That chance meeting led him to finish his undergraduate degree, and from there obtain an MFA from The George Washington University (Washington, D.C.).

After his graduation, and subsequent founding of his own dance company, the text feels more like a picture album of his life and career – with chapters as snapshots of separate pivotal moments on his choreographic journey. Just as does his choreography, this approach has much to demonstrate for us about effective structure; less can be more, through revealing the essence of the meaning at hand.

Many of these snapshots detail stories that are undoubtedly relatable to many dance artists, and demonstrate the strong stuff that dancers are made of – what they need to be made of to move forward in the work. For example, one opportunity had him dancing at the United Nations – marvelous! The only thing was that he had no technical rehearsal for a very challenging (and potentially dangerous) site-specific performance. Sink or swim, as they say. “…a dancer must always be prepared to be flexible, limber in body but also in attitude,” Burgess affirms. Indeed!

Another memorable story from his early career was staging Hans Christian Andersen’s The Nightingale with a group of 20 youth students of Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Thai and Filipino descent. Burgess led these students to a performance that complicated and modernized the original tale’s Orientalism – featuring “robotic dance phrases blending modern dance, hip hop and martial arts, juxtaposed to the natural flowing movements of the real Nightingale.”

Yet, when the work went on tour, new collaborators and unfortunate leadership decisions brought the work back to a more Orientalist feel. This instance demonstrates how making live art involves a plethora of players with hands in the mix – and only so much is within our control. We continue on, doing our best to hold on to our vision and our highest integrity.

A bit later in his choreographic and performance career, his collaborations with sculptor John Dreyfuss produced arguably groundbreaking work at the intersection of dance and visual art. From haunted homes (literally), to interfacing with the charming eccentricities of a fellow artist, to – yes, serendipitous – meetings with new power brokers and artistic heavy hitters: this chapter illustrates how good, bad, or ugly, the life of an artist remains quite the wild ride.

Here we also see how that dance and visual art intersection has also been one of consistent fascination and inspiration for Burgess. After all, he is the son of visual artists. He would spend hours in Washington, D.C.’s numerous museums during his graduate school years, sketching and feeling drawn to the movement within – and potentially emanating from – the art before him.

Burgess brings forward another of the text’s intriguing extended metaphors in this chapter, that of negotiatory dancing with such power brokers and heavy hitters. As artists, we dance literally and figuratively. Following chapters, as a sort of informal middle section of the text, describe a select number of Burgess’ international journeys: for making new choreographic work, teaching, creative research, and more. These “seminal touring experiences ….challenged and expanded my understanding of my own art form,” he shares. The monarch needs to migrate.

A choreographic research trip to Pakistan impressed upon him the place of dance, movement, and personal expression as an essential human right. His trip to Korea solidified certain traits of his own artistic signature, and illustrated for him how he is Korean and how he is American. Setting work on the Lima-based Ballet Nacional del Perú demonstrated to him the power of the just-right approach and just-right person in charge to address a problem arising in creative process – not to mention, that of spirits; don’t scoff at the otherworldly things that our boundaried human brains can’t quite grasp.

A trip to Germany to meet the late, great choreographer John Neumeier – among other nuggets of wisdom – inspired him to gather emblems of creative and personal meaning, to leave behind minimalism and embrace what could fuel him creatively. More importantly, losing a friend and mentor in Numeier – and taking the journey of grief with others who loved him – highlights the importance of holding close those dear to us. Life is short and too few are the people who will stand by us when we truly need it.

Serendipity and Synchronicity were on his side again in the subsequent chapter, when he made the work Hyphen. Yet so was his fortitude and courage to ask for, and keep searching for, what he needed to realize his vision. After all, artists must be limber of body and of mind – and also not give up so easily.

Later chapters in the text even more clearly demonstrate that need for persistence, for pure grit, to make a vision come to life. A board retreat brought Burgess to the realization that his next creative challenge would be bringing dance into museums. After much institutional resistance from museum powers-that-be, Burgess came to set lauded dance works in The Corcoran Gallery of Art, The National Gallery of Art and The Kreeger Museum. As a sweet and concrete affirmation of all of this hard work, he became the National Portrait Gallery’s first ever Choreographer in Residence in 2016.

An arguable pinnacle came with being invited for his work to be danced for President Barack Obama (and staff, members of his administration, and other luminaries) at the White House. Burgess underscores how after all of his struggles finding his place and his voice, after so much feeling like an outsider, just how meaningful this occasion was for him. My heart felt that to be as true as true could be.

Certainly, not all artists will have the leader of the free world view their work. Much of Burgess’ journey is as wonderfully singular as he is. Yet, there is much in his story that vibrantly illustrates the struggles, joys, epiphanies, treasures – and much, much more – that are common to the journey of each person who shapes movement into art.

Overall, his story is a reminder to keep pushing forward, yet not let the jewels of the now pass by unappreciated. Burgess wants “upcoming generations of dance artists to believe in their own footsteps…to stop and behold the wisdom of butterflies.” This writer can’t say it any better!

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.